Graded exercise therapy

| Graded exercise therapy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | GET |

| Specialty | Physical therapy |

Graded exercise therapy (GET) is a controversial programme of physical activity that starts very slowly and gradually increases over time. Intended as a treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS or ME/CFS), its safety and effectiveness are disputed. GET is not recommended by the CDC and NICE specifically warns against it, but the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners still supports its use.

Description

A graded exercise programme starts with a physiotherapist or exercise therapist assessing the patient's current abilities and negotiating goals. The patient then begins exercising at a level within their capabilities. The patient and therapist increase the duration of sessions, typically by 10-20% every 1-2 weeks, until they can perform 30 minutes of light exercise five times a week. Then the intensity is raised if desired.

The exercise can be any activity that can be titrated, such as walking, jogging, swimming, using exercise machines, and these may be mixed to add variety. Increasing the intensity can be more challenging than increasing duration, and a heart rate monitor may be employed to track intensity. If exercise exacerbates a patient's symptoms, they are encouraged to pause the increases until symptoms become manageable again.

Patients are told that if exercise provokes symptoms, it is a typical response to becoming more active rather than a pathological process that causes permanent damage. Adverse effects may be increased if the practitioner is unfamiliar with CFS or exercise is not ramped up appropriately.

Model

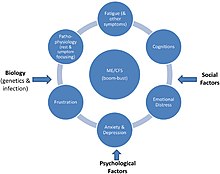

GET is based on the belief that people with ME/CFS avoid exerting themselves due to fear of triggering symptoms such as pain and fatigue, which causes deconditioning and further worsening of symptoms. Excessive focus on symptoms and attributing illness to biological factors are also said perpetuate the illness.

This model has been criticized as lacking evidence, contradicting patient experience, and not accounting for biological evidence that ME/CFS is a serious medical condition. According to several health agencies, mental health problems or deconditioning do not cause ME/CFS.

Criticism and support

Due to concerns over the quality of supporting evidence, graded exercise therapy is not recommended by the CDC or NICE. The CDC stopped recommending GET in 2017, and says that people with ME/CFS do not tolerate vigorous exercise. NICE's 2021 guidance for ME/CFS removed graded exercise, which was recommended in the previous 2007 version, and cautions against "any programme that...uses fixed incremental increases in physical activity or exercise, for example, graded exercise therapy." According to NICE, studies of GET have been of poor or very poor quality.

Two regional departments of health, in New York state and Victoria, Australia, say GET is ineffective and potentially dangerous.

The Mayo Clinic consensus recommendations for the treatment of ME/CFS say GET is an outdated standard of care that can worsen the condition. According to these recommendations, GET studies have poor methodology and fail to report harms, GET is built on a disproved disease model.

Patient groups for ME/CFS strongly oppose GET. The ME Association asserts that GET causes a significant fraction of patients to get worse: 30% to 50% in self-reporting patient questionnaires. According to the Mayo Clinic Proceedings recommendations, 54% to 74% reported harm.

As of 2015, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners still supports graded exercise for CFS.

A 2019 Cochrane review of 8 studies concluded that GET "probably" reduces fatigue but that evidence on long-term effectiveness and potential harms are very limited. The studies analyzed employed older definitions of CFS, so the effects on current patient cohorts may be different. An independent analysis of the same studies reached the opposite conclusion based on the unreliability of subjective outcomes in unblinded trials, lack of objective improvements in physical fitness and employment, and insufficient tracking of adverse events.

Research

The largest study on GET, the 2011 PACE trial, reported that GET and cognitive-behavioral therapy were safe and resulted in recovery for 22% of participants and improvement for 60%. However, the trial's results generated considerable controversy. Outcome measures were modified mid-trial without a clear rationale. When the data were reanalyzed utilising the original protocol, the rate of improvement was only 21%, and recovery was just 4%. While trial participants reported subjective improvement, there was no clinically significant improvement in fitness according to the 6-minute walk test, an objective outcome.

A 2022 review commissioned by the CDC concluded that weak evidence suggests that GET has "small to moderate" benefits, including reduced fatigue, decreased depression and anxiety, and better sleep. It said these results are of uncertain relevance to people with severe ME/CFS, a diagnosis according to modern criteria, or post-exertional malaise. According to the review, limited evidence suggests that GET is not harmful, but that reporting of harms was "suboptimal."

In 2021, a small study was published concerning the efficiency of GET at a specialist clinic in London, England. The patients were adults had an confirmed diagnosis of CFS according to NICE guidelines ("fatigue to be present for at least four months"). The study concluded that "GET therapy is a safe and efficacious treatment for patients with CFS/ME in a clinical specialist environment". Over the course of the treatment the average SF-36 Physical Functioning Subscale rose from 45.42 to 54.44, and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) fell from 25.25 to 21.48. However, an independent review of this study showed that fewer than half of the patients actually completed the full number of treatment sessions suggesting they were poorly tolerated, and that the data did not support the conclusion of "efficacious treatment"; a Physical functioning (SF-36) score of 65 or less still equates to "severe disability" and a WSAS score of greater than 20 indicates "moderately severe disability".