Health effects of trans fats

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

Trans fat, also called trans-unsaturated fatty acids, or trans fatty acids, is a type of unsaturated fat that occurs in foods. Trace concentrations of trans fats occur naturally, but large amounts are found in some processed foods. Since consumption of trans fats is unhealthy, artificial trans fats are highly regulated or banned in many nations. However, they are still widely consumed in developing nations, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. Serious interest has been given to determining their sources, to better avoid them.

Occurrence

Some trans fats arise naturally, and some are the result of human actions.

Naturally-occurring trans fats

Trans fats occur in meat and dairy products from ruminants. For example, butter contains about 3% trans fat. These trans fats arise from the action of bacteria in the rumen. In contrast to industrially produced trans fats, the bacterial produced versions exist only as a few isomers. Polyunsaturated fats are toxic to the rumen-based bacteria, which induces the latter to detoxify the fats by changing some cis-double bonds to trans. As industrial sources of trans fats are eliminated, increased attention focuses on ruminant derived trans fats.The fats derived from vaccenic acid are found in breast milk.

The trans fatty acid vaccenic acid has health benefits. Small amounts occur in meat and milk fat.

Hydrogenation

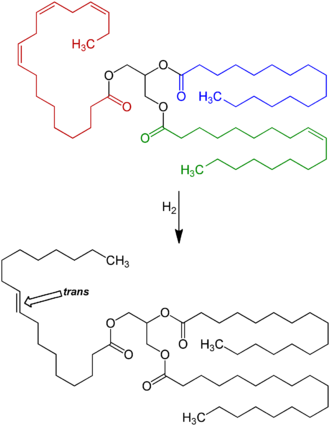

Trans fat can be an unintentional byproduct of the industrial processing of oils. Unlike naturally derived trans fats, the trans fats that result from hydrogenation consist of many isomers. In food production, liquid cis-unsaturated fats such as vegetable oils are hydrogenated to produce more saturated fats, which have desirable properties. For example, the shelf life of fats correlates with the degree of saturation: polyunsaturated fats are prone to autoxidation whereas saturated fats, being virtually inert in air, have very long shelf lives. Hydrogenation is practiced on a large scale in the production of margarine. The technology has improved such that a 2021 review indicate that the problem has been solved in modern countries. For example, trans fats levels can be minimized by using interesterified fat.

Thermal isomerization

When heated (cooked), some unsaturated fats change from their normal geometry to trans. The rate of isomerization is accelerated by free radicals.

History

The German chemist Wilhelm Normann showed that liquid oils could be hydrogenated. He patented the process in 1902. During the years 1905–1910, Normann built a fat-hardening facility in the Herford company. At the same time, the invention was extended to a large-scale plant in Warrington, England, at Joseph Crosfield & Sons, Limited. It took only two years until the hardened fat could be successfully produced in the plant in Warrington, commencing production in the autumn of 1909. The initial year's production totalled nearly 3,000 tonnes. In 1909, Procter & Gamble acquired the United States rights to the Normann patent; in 1911, they began marketing the first hydrogenated shortening, Crisco (composed largely of partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil). Further success came from the marketing technique of giving away free cookbooks in which every recipe called for Crisco.

Normann's hydrogenation process made it possible to stabilize affordable whale oil or fish oil for human consumption, a practice kept secret to avoid consumer distaste.

Before 1910, dietary fats in industrialized nations consisted mostly of butterfat, beef tallow, and lard. During Napoleon's reign in France in the early 19th century, a type of margarine was invented to feed the troops using tallow and buttermilk, but this was not accepted in the U.S. In the early 20th century, soybeans began to be imported into the U.S. as a source of protein; soybean oil was a by-product. What to do with that oil became an issue. At the same time, there was not enough butterfat available for consumers. The method of hydrogenating fat and turning a liquid fat into a solid one had been discovered, and now the ingredients (soybeans) and the need (shortage of butter) were there. Later, the means for storage, the refrigerator, was a factor in trans fat development. The fat industry found that hydrogenated fats provided some special features to margarines, which allowed margarine, unlike butter, to be taken out of a refrigerator and immediately spread on bread. By some minor changes to the chemical composition of hydrogenated fat, such hydrogenated fat was found to provide superior baking properties compared to lard. Margarine made from partially hydrogenated soybean oil began to replace butterfat. Partially hydrogenated fat such as Crisco and Spry, sold in England, began to replace butter and lard in baking bread, pies, cookies, and cakes in 1920.

Production of partially hydrogenated fats increased steadily in the 20th century as processed vegetable fats replaced animal fats in the U.S. and other Western countries. At first, the argument was a financial one due to lower costs; advocates also said that the unsaturated trans fats of margarine were healthier than the saturated fats of butter.

As early as 1956, there were suggestions in the scientific literature that trans fats could be a cause of the large increase in coronary artery disease but after three decades the concerns were still largely unaddressed. Instead, by the 1980s, fats of animal origin had become one of the greatest concerns of dieticians. Activists, such as Phil Sokolof, who took out full page ads in major newspapers, attacked the use of beef tallow in McDonald's French fries and urged fast-food companies to switch to vegetable oils. The result was an almost overnight switch by most fast-food outlets to trans fats.

Studies in the early 1990s, however, brought renewed scrutiny and confirmation of the negative health impact of trans fats. In 1994, it was estimated that trans fats caused at least 20,000 deaths annually in the U.S. from heart disease.

Mandatory food labeling for trans fats was introduced in several countries. Campaigns were launched by activists to bring attention to the issue and change the practices of food manufacturers. In January 2007, faced with the prospect of an outright ban on the sale of their product, Crisco was reformulated to meet the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) definition of "zero grams trans fats per serving" (that is less than one gram per tablespoon, or up to 7% by weight; or less than 0.5 grams per serving size) by boosting the saturation and then diluting the resulting solid fat with unsaturated vegetable oils.

Structure

A fatty acid is characterized as either saturated or unsaturated based on the respective absence of presence of C=C double bonds in its backbone. If the molecule contains no double C=C bonds, it is said to be saturated; otherwise, it is unsaturated to some degree.

The C=C double bond is rotationally rigid. If the hydrogen bonded to each of the carbons in this double bond are on the same side, this is called cis, and leads to a bent molecular chain. If the two hydrogens are on opposite sides, this is called trans, and leads to a straight chain. See figures below.

Because trans fats are more linear, they crystallize more easily, allowing them to be solid (rather than liquid) at room temperatures. This has several processing and storage advantages.

In nature, unsaturated fatty acids generally have cis configurations as opposed to trans configurations. Saturated fatty acids (those without any carbon-carbon double bonds are abundant (see tallow), but they also can be generated from unsaturated fats by the process of fat hydrogenation. In the course of hydrogenation, some cis double bonds convert into trans double bonds. Chemists call this conversion an isomerization reaction.

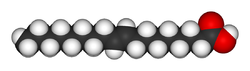

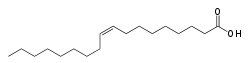

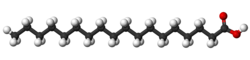

| Trans (Elaidic acid) | Unsaturated (Oleic acid) | Saturated (Stearic acid) |

|---|---|---|

| Elaidic acid is the main trans unsaturated fatty acid often found in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils. | Oleic acid is a cis unsaturated fatty acid making up 55–80% of olive oil. | Stearic acid is a saturated fatty acid found in animal fats and is the intended product in full hydrogenation. Stearic acid is neither unsaturated nor trans because it has no carbon-carbon double bonds. |

|

||

| These fatty acids are geometric isomers (structurally identical except for the arrangement of the double bond). | This fatty acid contains no carbon-carbon double bonds and is not isomeric with the prior two. | |

Hydrogenation of an unsaturated fatty acid is intended to convert unsaturated fatty acids (and unsaturated fats) to saturated derivatives. The hydrogenation process however can cause cis C=C bonds to become trans. Typical commercial hydrogenation is partial to obtain a malleable mixture of fats that is solid at room temperature, but melts during baking, or consumption.

The same molecule, containing the same number of atoms, with a double bond in the same location, can be either a trans or a cis fatty acid depending on the configuration of the double bond. For example, oleic acid and elaidic acid are both unsaturated fatty acids with the chemical formula C9H17C9H17O2. They both have a double bond located midway along the carbon chain. It is the configuration of this bond that sets them apart. The configuration has implications for the physical-chemical properties of the molecule. The trans configuration is straighter, while the cis configuration is noticeably kinked as can be seen from the three-dimensional representation shown above. Cis- and trans fatty acids (and their derivatives) have distinct chemical (and metabolic) properties, For example, the melting point of elaidic acid is 45 °C higher than that of oleic acid. This notably means that it is a solid at human body temperatures.

In the sense of food production, however, the goal is not necessarily to simply change the configuration of double bonds while maintaining the same ratios of hydrogen to carbon; rather, the goal is to decrease the number of double bonds (when a fatty acid molecule contains more than one double bond it is classified as "polyunsaturated") by increasing the amount of hydrogen (and, thus, single bonds) in the fatty acid. This subsequent lesser degree of unsaturation (and, simultaneously, greater degree of saturation) thereby changes the consistency of the fatty acid by way of allowing its molecules to more greatly compress and congeal and in turn thereby makes it less prone to rancidity (in which free radicals attack double bonds). In this second sense of the goal being to simply reduce the degree of unsaturation in an unsaturated fatty acid, the production of trans fatty acids is thus an undesirable side effect of partial hydrogenation.

Catalytic partial hydrogenation produces some trans-fats. The standard 140 kPa (20 psi) process of hydrogenation produces a product of about 40% trans fatty acid by weight, compared to about 17% using higher pressures of hydrogen. Blended with unhydrogenated liquid soybean oil, the high-pressure-processed oil produced margarine containing 5 to 6% trans fat. Based on current U.S. labeling requirements (see below), the manufacturer could claim the product was free of trans fat. The level of trans fat may also be altered by modification of the temperature and the length of time during hydrogenation.

The trans fat levels can be quantified using various forms of chromatography.

Presence in food

| Food type | Trans fat content |

|---|---|

| shortenings | 10 - 33 g |

| margarine, stick | 6.2-16.8 |

| butter | 2 - 7 g |

| whole milk | 0.07 - 0.1 g |

| breads/cake products | 0.1 - 10 g |

| cookies and crackers | 1 - 8 g |

| tortilla chips | 5.8 g |

| cake frostings, sweets | 0.1 - 7 g |

| animal fat | 0 - 5 g |

| ground beef | 1 g |

A type of trans fat occurs naturally in the milk and body fat of ruminants (such as cattle and sheep) at a level of 2–5% of total fat. Natural trans fats, which include conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and vaccenic acid, originate in the rumen of these animals. CLA has two double bonds, one in the cis configuration and one in trans, which makes it simultaneously a cis- and a trans-fatty acid.

Animal-based fats were once the only trans fats consumed, but by far the largest amount of trans fat consumed today is created by the processed food industry as a side effect of partially hydrogenating unsaturated plant fats (generally vegetable oils). These partially hydrogenated fats have displaced natural solid fats and liquid oils in many areas, the most notable ones being in the fast food, snack food, fried food, and baked goods industries.

Partially hydrogenated oils have been used in food for many reasons. Hydrogenation increases product shelf life and decreases refrigeration requirements. Many baked foods require semi-solid fats to suspend solids at room temperature; partially hydrogenated oils have the right consistency to replace animal fats such as butter and lard at lower cost. They are also an inexpensive alternative to other semi-solid oils such as palm oil.

Up to 45% of the total fat in those foods containing man-made trans fats formed by partially hydrogenating plant fats may be trans fat. Baking shortenings, unless reformulated, contain around 30% trans fats compared to their total fats. High-fat dairy products such as butter contain about 4%. Margarines not reformulated to reduce trans fats may contain up to 15% trans fat by weight, but some reformulated ones are less than 1% trans fat.

It has been established that trans fats in human breast milk fluctuate with maternal consumption of trans fat, and that the amount of trans fats in the bloodstream of breastfed infants fluctuates with the amounts found in their milk. In 1999, reported percentages of trans fats (compared to total fats) in human milk ranged from 1% in Spain, 2% in France, 4% in Germany, and 7% in Canada and the U.S.

Trans fats are used in shortenings for deep-frying in restaurants, as they can be used for longer than most conventional oils before becoming rancid. In the early 21st century, non-hydrogenated vegetable oils that have lifespans exceeding that of the frying shortenings became available. As fast-food chains routinely use different fats in different locations, trans fat levels in fast food can have large variations. For example, an analysis of samples of McDonald's French fries collected in 2004 and 2005 found that fries served in New York City contained twice as much trans fat as in Hungary, and 28 times as much as in Denmark, where trans fats are restricted. At KFC, the pattern was reversed, with Hungary's product containing twice the trans fat of the New York product. Even within the U.S. there was variation, with fries in New York containing 30% more trans fat than those from Atlanta.

Nutritional guidelines

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) advises the U.S. and Canadian governments on nutritional science for use in public policy and product labeling programs. Their 2002 Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids contains their findings and recommendations regarding consumption of trans fat (summary).

Their recommendations are based on two key facts. First, "trans fatty acids are not essential and provide no known benefit to human health", whether of animal or plant origin. Second, while both saturated and trans fats increase levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), trans fats also lower levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), thus increasing the risk of coronary artery disease. The NAS is concerned "that dietary trans fatty acids are more deleterious with respect to coronary artery disease than saturated fatty acids". This analysis is supported by a 2006 New England Journal of Medicine scientific review that states "from a nutritional standpoint, the consumption of trans fatty acids results in considerable potential harm but no apparent benefit."

Because of these facts and concerns, the NAS has concluded there is no safe level of trans fat consumption. There is no adequate level, recommended daily amount or tolerable upper limit for trans fats. This is because any incremental increase in trans fat intake increases the risk of coronary artery disease.

Despite this concern, the NAS dietary recommendations have not included eliminating trans fat from the diet. This is because trans fat is naturally present in many animal foods in trace quantities, and thus its removal from ordinary diets might introduce undesirable side effects and nutritional imbalances if proper nutritional planning is not undertaken. The NAS has, thus, "recommended that trans fatty acid consumption be as low as possible while consuming a nutritionally adequate diet". Like the NAS, the World Health Organization has tried to balance public health goals with a practical level of trans fat consumption, recommending in 2003 that trans fats be limited to less than 1% of overall energy intake.

The US National Dairy Council has asserted that the trans fats present in foods of animal origin are of a different type than those in partially hydrogenated oils, and do not appear to exhibit the same negative effects. A scientific review agrees with the conclusion (stating that "the sum of the current evidence suggests that the Public health implications of consuming trans fats from ruminant products are relatively limited") but cautions that this may be due to the low consumption of trans fats from animal sources compared to artificial ones.

A meta-analysis showed that all trans fats, regardless of natural or artificial origin equally raise LDL and lower HDL levels. Other studies though have shown different results when it comes to animal based trans fats like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Although CLA is known for its anticancer properties, researchers have also found that the cis-9, trans-11 form of CLA can reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease and help fight inflammation.

Health risks

Partially hydrogenated vegetable oils were an increasingly significant part of the human diet for about 100 years, especially after 1950 as processed food rose in popularity. The deleterious effects of trans fat consumption are scientifically accepted.

Intake of dietary trans fat disrupts the body's ability to metabolize essential fatty acids (EFAs, including Omega-3) leading to changes in the phospholipid fatty acid composition of the arterial walls, thereby raising risk of coronary artery disease.

While the mechanisms through which trans fatty acids contribute to coronary artery disease are understood, the mechanism for their effects on diabetes is still under investigation. They may impair the metabolism of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), but maternal pregnancy trans fatty acid intake has been inversely associated with LCPUFAs levels in infants at birth thought to underlie the positive association between breastfeeding and intelligence.

Consumption of industrial trans fat in the form of partially hydrogenated oil causes many health problems. They were abundant in fast food restaurants. They are consumed in greater quantities by people who lack access to a diet consisting of fewer partially-hydrogenated fats, or who often consume fast food. A diet high in trans fats can contribute to obesity, high blood pressure, and higher risk for heart disease. Trans fat is also implicated in Type 2 diabetes.

Coronary artery disease

The most important health risk identified for trans fat consumption is an elevated risk of coronary artery disease (CAD). A 1994 study estimated that over 30,000 cardiac deaths per year in the U.S. are attributable to the consumption of trans fats. By 2006 upper estimates of 100,000 deaths were suggested. A comprehensive review of studies of trans fats published in 2006 in the New England Journal of Medicine reports a strong and reliable connection between trans fat consumption and CAD, concluding that "On a per-calorie basis, trans fats appear to increase the risk of CAD more than any other macronutrient, conferring a substantially increased risk at low levels of consumption (1 to 3% of total energy intake)".

The major evidence for the effect of trans fat on CAD comes from the Nurses' Health Study – a cohort study that has been following 120,000 female nurses since its inception in 1976. In this study, Hu and colleagues analyzed data from 900 coronary events from the study's population during 14 years of followup. He determined that a nurse's CAD risk roughly doubled (relative risk of 1.93, CI: 1.43 to 2.61) for each 2% increase in trans fat calories consumed (instead of carbohydrate calories). By contrast, for each 5% increase in saturated fat calories (instead of carbohydrate calories) there was a 17% increase in risk (relative risk of 1.17, CI: 0.97 to 1.41). "The replacement of saturated fat or trans unsaturated fat by cis (unhydrogenated) unsaturated fats was associated with larger reductions in risk than an isocaloric replacement by carbohydrates." Hu also reports on the benefits of reducing trans fat consumption. Replacing 2% of food energy from trans fat with non-trans unsaturated fats more than halves the risk of CAD (53%). By comparison, replacing a larger 5% of food energy from saturated fat with non-trans unsaturated fats reduces the risk of CAD by 43%.

Another study considered deaths due to CAD, with consumption of trans fats being linked to an increase in mortality, and consumption of polyunsaturated fats being linked to a decrease in mortality.

There are two accepted tests that measure an individual's risk for coronary artery disease, both blood tests. The first considers ratios of two types of cholesterol, the other the amount of a cell-signalling cytokine called C-reactive protein. The ratio test is more accepted, while the cytokine test may be more powerful but is still being studied. The effect of trans fat consumption has been documented on each as follows:

- Cholesterol ratio: This ratio compares the levels of LDL to HDL. Trans fat behaves like saturated fat by raising the level of LDL, but, unlike saturated fat, it has the additional effect of decreasing levels of HDL. The net increase in LDL/HDL ratio with trans fat is approximately double that due to saturated fat. (Higher ratios are worse.) One randomized crossover study published in 2003 comparing the effect of eating a meal on blood lipids of (relatively) cis and trans fat rich meals showed that cholesteryl ester transfer (CET) was 28% higher after the trans meal than after the cis meal and that lipoprotein concentrations were enriched in apolipoprotein(a) after the trans meals.

- C-reactive protein (CRP): A study of over 700 nurses showed that those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption had blood levels of CRP that were 73% higher than those in the lowest quartile.

Other health risks

Scientific studies have examined other negative effects of industrial trans fat beyond cardiovascular disease, with the next most studied area being type-2 diabetes.

- Alzheimer's disease: A study published in Archives of Neurology in February 2003 suggested that the intake of both trans fats and saturated fats promote the development of Alzheimer disease, although not confirmed in an animal model. It has been found that trans fats impaired memory and learning in middle-age rats. The trans-fat eating rats' brains had fewer proteins critical to healthy neurological function and inflammation in and around the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for learning and memory. These are the exact types of changes normally seen at the onset of Alzheimer's, but seen after six weeks, even though the rats were still young.

- Cancer: In 2007 the American Cancer Society stated that a relationship between trans fats and cancer "has not been determined." One study has found a positive connection between trans fat and prostate cancer. However, a larger study found a correlation between trans fats and a significant decrease in high-grade prostate cancer. An increased intake of trans fatty acids may raise the risk of breast cancer by 75%, suggest the results from the French part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.

- Diabetes: There is a growing concern that the risk of type 2 diabetes increases with trans fat consumption. However, consensus has not been reached. For example, one study found that risk is higher for those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption. Another study has found no diabetes risk once other factors such as total fat intake and BMI were accounted for.

- Obesity: Research indicates that trans fat may increase weight gain and abdominal fat, despite a similar caloric intake. A 6-year experiment revealed that monkeys fed a trans fat diet gained 7.2% of their body weight, as compared to 1.8% for monkeys on a mono-unsaturated fat diet. Although obesity is frequently linked to trans fat in the popular media, this is generally in the context of eating too many calories; there is not a strong scientific consensus connecting trans fat and obesity, although the 6-year experiment did find such a link, concluding that "under controlled feeding conditions, long-term TFA consumption was an independent factor in weight gain. TFAs enhanced intra-abdominal deposition of fat, even in the absence of caloric excess, and were associated with insulin resistance, with evidence that there is impaired post-insulin receptor binding signal transduction."

- Liver dysfunction: Trans fats are metabolized differently by the liver than other fats and interfere with delta 6 desaturase. Delta 6 desaturase is an enzyme involved in converting essential fatty acids to arachidonic acid and prostaglandins, both of which are important to the functioning of cells.

- Infertility in women: One 2007 study found, "Each 2% increase in the intake of energy from trans unsaturated fats, as opposed to that from carbohydrates, was associated with a 73% greater risk of ovulatory infertility...".

- Major depressive disorder: Spanish researchers analysed the diets of 12,059 people over six years and found that those who ate the most trans fats had a 48 per cent higher risk of depression than those who did not eat trans fats. One mechanism may be trans-fats' substitution for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) levels in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). Very high intake of trans-fatty acids (43% of total fat) in mice from 2 to 16 months of age was associated with lowered DHA levels in the brain (p=0.001). When the brains of 15 major depressive subjects who had committed suicide were examined post-mortem and compared against 27 age-matched controls, the suicidal brains were found to have 16% less (male average) to 32% less (female average) DHA in the OFC. The OFC controls reward, reward expectation, and empathy (all of which are reduced in depressive mood disorders) and regulates the limbic system.

- Behavioral irritability and aggression: a 2012 observational analysis of subjects of an earlier study found a strong relation between dietary trans fat acids and self-reported behavioral aggression and irritability, suggesting but not establishing causality.

- Diminished memory: In a 2015 article, researchers re-analyzing results from the 1999-2005 UCSD Statin Study argue that "greater dietary trans fatty acid consumption is linked to worse word memory in adults during years of high productivity."

- Acne: According to a 2015 study, trans fats are one of several components of Western pattern diets which promote acne, along with carbohydrates with high glycemic load such as refined sugars or refined starches, milk and dairy products, and saturated fats, while omega-3 fatty acids, which reduce acne, are deficient in Western pattern diets.

Public response and regulation

For additional detail on laws and movements to limit and ban trans fat and partially hydrogenated oil, see the article Trans fat regulation.

International

The international trade in food is standardized in the Codex Alimentarius. Hydrogenated oils and fats come under the scope of Codex Stan 19. Non-dairy fat spreads are covered by Codex Stan 256-2007. In the Codex Alimentarius, trans fat to be labelled as such is defined as the geometrical isomers of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids having non-conjugated [interrupted by at least one methylene group (−CH2−)] carbon-carbon double bonds in the trans configuration. This definition excludes specifically the trans fats (vaccenic acid and conjugated linoleic acid) that are present especially in human milk, dairy products, and beef.

in 2018 the World Health Organization launched a plan to eliminate trans fat from the global food supply. They estimate that trans fat leads to more than 500,000 deaths from cardiovascular disease yearly.

Argentina

Trans fat content labeling is required starting in August 2006. Since 2010, vegetable oils and fats sold to consumers directly must contain only 2% of trans fat over total fat, and other food must contain less than 5% of their total fat. Starting on 10 December 2014, Argentina has on effect a total ban on food with trans fat, a regulation that could save the government more than US$100 million a year on healthcare.

Australia

The former federal assistant health minister, Christopher Pyne, asked fast food outlets to reduce their trans fat use. A draft plan was proposed, with a September 2007 timetable, to reduce reliance on trans fats and saturated fats.

As of 2018, Australia's food labeling laws do not require trans fats to be shown separately from the total fat content. However, margarine in Australia has been mostly free of trans fat since 1996.

Austria

Trans fat content is limited to 4% of total fat, or 2% on products that contain more than 20% fat.

Belgium

The Conseil Supérieur de la Santé published in 2012 a science-policy advisory report on industrially produced trans fatty acids that focuses on the general population. Its recommendation to the legislature was to prohibit more than 2 g of trans fatty acids per 100 g of fat in food products.

Brazil

Resolution 360, dated December 23, 2003, by the Brazilian ministry of health required the amount of trans fat to be specified in labels of food products. On 31 July 2006, such labeling of trans fat contents became mandatory. In 2019 Anvisa published a new legislation to reduce the total amount of trans fat in any industrialized food sold in Brazil to a maximum of 2% by the end of 2023.

Canada

In a process that began in 2004, Health Canada finally banned partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs), the primary source of industrially produced trans fats in foods, in September 2018.

On 15 September 2017, Health Canada announced that trans fat would be completely banned effective on 15 September 2018. and the ban came into effect in September 2018, banning partially hydrogenated oils (the largest source of industrially produced trans fats in foods). It is now illegal for manufacturers to add partially hydrogenated oils to foods sold in or imported into Canada.

Public perception

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Regina, Saskatchewan in February 2009 at 3 different grocery stores located in 3 different regions that had the same median income before taxes of around $30,000. Of the 211 respondents to the study, most were women who purchased most of the food for their household. When asked how they decide what food to buy, the most important factors were price, nutritional value, and need. When looking at the nutritional facts, however, they indicated that they looked at the ingredients, and neglected to pay attention to the amount of trans fat. This means that trans fat is not on their minds unless they are specifically told of it. When asked if they ever heard about trans fat, 98% said, "Yes." However, only 27% said that it was unhealthy. Also, 79% said that they only knew a little about trans fats, and could have been more educated. Respondents aged 41–60 were more likely to view trans fat as a major health concern, compared to ages 18–40. When asked if they would stop buying their favorite snacks if they knew it contained trans fat, most said they would continue purchasing it, especially the younger respondents. Also, of the respondents that called trans fat a major concern, 56% of them still wouldn't change their diet to non-trans fat snacks. This is because taste and food gratification take precedence over perceived risk to health. "The consumption of trans fats and the associated increased risk of CHD is a public health concern regardless of age and socioeconomic status".

Denmark

Denmark became the first country to introduce laws strictly regulating the sale of many foods containing trans fats in March 2003, a move that effectively bans partially hydrogenated oils. The limit is 2% of fats and oils destined for human consumption. This restriction is on the ingredients rather than the final products. This regulatory approach has made Denmark the first country in which it is possible to eat "far less" than 1 g of industrially produced trans fats daily, even with a diet including prepared foods. It is hypothesized that the Danish government's efforts to decrease trans fat intake from 6 g to 1 g per day over 20 years is related to a 50% decrease in deaths from ischemic heart disease.

European Union

In 2004, the European Food Safety Authority produced a scientific opinion on trans fatty acids, surmising that "higher intakes of TFA may increase risk for coronary heart disease".

From 2 April 2021 foods in the EU intended for consumers are required to contain less than 2g of industrial trans fat per 100g of fat.

Greece

Law in Greece limits content of trans fats sold in school canteens to 0.1% (Ministerial Decision Υ1γ/ΓΠ/οικ 81025/ΦΕΚ 2135/τ.Β’/29-08-2013 as modified by Ministerial Decision Υ1γ/ Γ.Π/οικ 96605/ΦΕΚ 2800 τ.Β/4-11-201).

Iceland

Total trans fat content was limited in 2010 to 2% of total fat content.

Israel

Since 2014, it is obligatory to mark food products with more than 2% (by weight) fat. The nutritional facts must contain the amount of trans fats.

Pakistan

Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan with the support of WHO has taken the initiative to eliminate trans fat from food chain in Pakistan. Vanaspati Ghee (partially hydrogenated fat) and Margarine have been identified as major dietary vectors for trans fat. PSQCA (Pakistan Standard and Quality Control Authority) has set the time line for the reduction of trans fat level as per recommendations of WHO by June 2023.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) requires importers and manufacturer to write the trans fats amounts in the nutritional facts labels of food products according to the requirements of Saudi Standard Specifications/Gulf Specifications. Starting in 2020, Saudi Minister of Health announced the ban of trans fat in all food products due to their health risks.

Singapore

The Ministry of Health announced on 6 March 2019 that partially-hydrogenated oils (PHOs) will be banned. A target is set to ban PHOs by June 2021, aiming to encourage healthy eating habits.

Sweden

The parliament gave the government a mandate in 2011 to submit without delay a law prohibiting the use of industrially produced trans fats in foods, as of 2017 the law has not yet been implemented.

Switzerland

Switzerland followed Denmark's trans fats ban, and implemented its own starting in April 2008.

United Kingdom

In October 2005, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) asked for better labelling in the UK. In the edition of 29 July 2006 of the British Medical Journal, an editorial also called for better labelling. In January 2007, the British Retail Consortium announced that major UK retailers, including Asda, Boots, Co-op Food, Iceland, Marks and Spencer, Sainsbury's, Tesco and Waitrose intended to cease adding trans fatty acids to their own products by the end of 2007.

Sainsbury's became the first UK major retailer to ban all trans fat from all their own store brand foods.

On 13 December 2007, the Food Standards Agency issued news releases stating that voluntary measures to reduce trans fats in food had already resulted in safe levels of consumer intake.

On 15 April 2010, a British Medical Journal editorial called for trans fats to be "virtually eliminated in the United Kingdom by next year".

The June 2010 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) report Prevention of cardiovascular disease declared that 40,000 cardiovascular disease deaths in 2006 were "mostly preventable". To achieve this, NICE offered 24 recommendations including product labelling, public education, protecting under–16s from marketing of unhealthy foods, promoting exercise and physically active travel, and even reforming the Common Agricultural Policy to reduce production of unhealthy foods. Fast-food outlets were mentioned as a risk factor, with (in 2007) 170 g of McDonald's fries and 160 g nuggets containing 6 to 8 g of trans fats, conferring a substantially increased risk of coronary artery disease death. NICE made three specific recommendation for diet: (1) reduction of dietary salt to 3 g per day by 2025; (2) halving consumption of saturated fats; and (3) eliminating the use of industrially produced trans fatty acids in food. However, the recommendations were greeted unhappily by the food industry, which stated that it was already voluntarily dropping the trans fat levels to below the WHO recommendations of a maximum of 2%.

Rejecting an outright ban, the Health Secretary Andrew Lansley launched on 15 March 2012 a voluntary pledge to remove artificial trans fats by the end of the year. Asda, Pizza Hut, Burger King, Tesco, Unilever and United Biscuits are some of 73 businesses who have agreed to do so. Lansley and his special Adviser Bill Morgan formerly worked for firms with interests in the food industry and some journalists have alleged that this results in a conflict of interest. Many health professionals are not happy with the voluntary nature of the deal. Simon Capewell, Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at the University of Liverpool, felt that justifying intake on the basis of average figures was unsuitable since some members of the community could considerably exceed this.

United States

Before 1 January 2006, consumers in the U.S. could not always determine the presence, or quantity, of trans fats from partially hydrogenated oils in food products, because this information was not required on the ingredient list before that date. In 2010, according to the FDA, the average American consumed 5.8 grams of trans fat per day (2.6% of energy intake). Monoglycerides and diglycerides are not considered fats by the FDA, despite their nearly equal calorie per weight contribution during ingestion.

On 11 July 2003, the FDA issued a regulation requiring manufacturers to list trans fat on the Nutrition Facts panel of foods and some dietary supplements. The new labeling rule became mandatory across the board on 1 January 2006, even for companies that petitioned for extensions. However, unlike in many other countries, trans fat levels of less than 0.5 grams per serving can be listed as 0 grams trans fat on the food label. According to a study published in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, without an interpretive footnote or further information on recommended daily value, many consumers do not know how to interpret the meaning of trans fat content on the Nutrition Facts panel. Without specific prior knowledge about trans fat and its negative health effects, consumers, including those at risk for heart disease, may misinterpret nutrient information provided on the panel. The FDA did not approve nutrient content claims such as "trans fat free" or "low trans fat", as they could not determine a "recommended daily value". Nevertheless, the agency is planning a consumer study to evaluate the consumer understanding of such claims and perhaps consider a regulation allowing their use on packaged foods. However, there is no requirement to list trans fats on institutional food packaging; thus bulk purchasers such as schools, hospitals, jails and cafeterias are unable to evaluate the trans fat content of commercial food items.

Critics of the plan, including FDA advisor Dr. Carlos Camargo, have expressed concern that the 0.5 gram per serving threshold is too high to refer to a food as free of trans fat. This is because a person eating many servings of a product, or eating multiple products over the course of the day may still consume a significant amount of trans fat. Despite this, the FDA estimates that by 2009, trans fat labeling will have prevented from 600 to 1,200 cases of coronary artery disease, and 250 to 500 deaths, yearly. This benefit is expected to result from consumers choosing alternative foods lower in trans fats, and manufacturers reducing the amount of trans fats in their products.

The American Medical Association supports any state and federal efforts to ban the use of artificial trans fats in U.S. restaurants and bakeries.

The American Public Health Association adopted a new policy statement regarding trans fats in 2007. These new guidelines, entitled Restricting Trans Fatty Acids in the Food Supply, recommend that the government require nutrition facts labeling of trans fats on all commercial food products. They also urge federal, state, and local governments to ban and monitor use of trans fats in restaurants. Furthermore, the APHA recommends barring the sales and availability of foods containing significant amounts of trans fat in public facilities including universities, prisons, and day care facilities etc.

On 7 November 2013, the FDA issued a preliminary determination that trans fats are not "generally recognized as safe", which was widely seen as a precursor to reclassifying trans fats as a "food additive," meaning they could not be used in foods without specific regulatory authorization. This would have the effect of virtually eliminating trans fats from the US food supply. The ruling was formally enacted on 16 June 2015, requiring that within three years, by 18 June 2018 no food prepared in the U.S. is allowed to include trans fats, unless approved by the FDA.

The FDA agreed in May 2018 to give companies one more year to find other ingredients for enhancing product flavors or greasing industrial baking pans, effectively banning trans fats in the U.S. from May 2019 onwards. Also, while new products can no longer be made with trans fats, they will give foods already on the shelves some time to cycle out of the market.

2015–2018 phaseout

In 2009, at the age of 94, University of Illinois professor Fred Kummerow, a trans fat researcher who had campaigned for decades for a federal ban on the substance, filed a petition with the FDA seeking elimination of artificial trans fats from the U.S. food supply. The FDA did not act on his petition for four years, and in 2013 Kummerow filed a lawsuit against the FDA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, seeking to compel the FDA to respond to his petition and "to ban partially hydrogenated oils unless a complete administrative review finds new evidence for their safety." Kummerow's petition stated that "Artificial trans fat is a poisonous and deleterious substance, and the FDA has acknowledged the danger."

Three months after the suit was filed, on 16 June 2015, the FDA moved to eliminate artificial trans fats from the U.S. food supply, giving manufacturers a deadline of three years. The FDA specifically ruled that trans fat was not generally recognized as safe and "could no longer be added to food after 18 June 2018, unless a manufacturer could present convincing scientific evidence that a particular use was safe." Kummerow stated: "Science won out."

The ban is believed to prevent about 90,000 premature deaths annually. The FDA estimates the ban will cost the food industry $6.2 billion over 20 years as the industry reformulates products and substitutes new ingredients for trans fat. The benefits are estimated at $140 billion over 20 years mainly from lower health care spending. Food companies can petition the FDA for approval of specific uses of partially hydrogenated oils if the companies submit data proving the oils' use is safe.

Food industry response

Manufacturer response

Palm oil, a natural oil extracted from the fruit of oil palm trees that is semi-solid at room temperature (15–25 degrees Celsius), can potentially serve as a substitute for partially hydrogenated fats in baking and processed food applications, although there is disagreement about whether replacing partially hydrogenated fats with palm oil confers any health benefits. A 2006 study supported by the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service concluded that palm oil is not a safe substitute for partially hydrogenated fats (trans fats) in the food industry, because palm oil results in adverse changes in the blood concentrations of LDL and apolipoprotein B just as trans fat does.

In May 2003, BanTransFats.com Inc., a U.S. non-profit corporation, filed a lawsuit against the food manufacturer Kraft Foods in an attempt to force Kraft to remove trans fats from the Oreo cookie. The lawsuit was withdrawn when Kraft agreed to work on ways to find a substitute for the trans fat in the Oreo.

The J.M. Smucker Company, then the American manufacturer of Crisco (the original partially hydrogenated vegetable shortening), in 2004 released a new formulation made from solid saturated palm oil cut with soybean oil and sunflower oil. This blend yielded an equivalent shortening much like the prior partially hydrogenated Crisco, and was labelled zero grams of trans fat per 1 tablespoon serving (as compared with 1.5 grams per tablespoon of original Crisco). As of 24 January 2007, Smucker claimed that all Crisco shortening products in the US have been reformulated to contain less than one gram of trans fat per serving while keeping saturated fat content less than butter. The separately marketed trans fat free version introduced in 2004 was discontinued.

On 22 May 2004, Unilever, the corporate descendant of Joseph Crosfield & Sons (the original producer of Wilhelm Normann's hydrogenation hardened oils) announced that they have eliminated trans fats from all their margarine products in Canada, including their flagship Becel brand.

Agribusiness giant Bunge Limited, through their Bunge Oils division, are now producing and marketing an NT product line of non-hydrogenated oils, margarines and shortenings, made from corn, canola, and soy oils.

Since 2003,Loders Croklaan, a wholly owned subsidiary of Malaysia's IOI Group has been providing trans fat free bakery and confectionery fats, made from palm oil, for giant food companies in the U.S. to make margarine.

Major users' response

Beginning around 2000, as the scientific evidence and public concern about trans fat increased, major American users of trans fat began to switch to safer alternatives. The process received a large boost in 2003 when the FDA announced it would require trans fat labeling on packaged food starting in 2006. Packaged food companies then faced the choice of either eliminating trans fat from their products, or having to declare the trans fat on their nutrition label. Lawsuits in the U.S. against trans fat users also encouraged its removal.

Major American fast food chains including McDonald's, Burger King, KFC and Wendy's reduced and then removed partially hydrogenated oils (containing artificial trans fats) by 2009. This was a major step toward trans fat removal, as french fries were one of the largest sources of trans fat in the American diet, with a large fries typically having about 6 grams of trans fat until around 2007.

Two other events were important in the removal of trans fat. First, in 2013 the FDA announced it planned to completely ban artificial trans fat in the form of partially hydrogenated oil. Second, soon after this, Wal-Mart informed its suppliers they needed to remove trans fat by 2015 if they wanted to continue to sell their products at its stores. As Wal-Mart is the largest brick-and-mortar retailer in the U.S., mainstream food brands had little choice but to comply.

These reformulations can be partly attributed to 2006 Center for Science in the Public Interest class action complaints, and to New York's restaurant trans fat ban, with companies such as McDonald's's stating they would not be selling a unique product just for New York customers but would implement a nationwide or worldwide change.

See also

Further reading

- Dijkstra, Albert; Hamilton, Richard J.; Wolf, Hamm, eds. (2008). Trans Fatty Acids. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5691-2.

- Jang ES, Jung MY, Min DB (2005). "Hydrogenation for Low Trans and High Conjugated Fatty Acids" (PDF). Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008.

External links

- "Ban the Trans: These Sorry Lipids Should Go Away"

- Center for Science in the Public Interest Trans Fat Page

- Harvard School of Public Health webpage on trans-fat

- "Labeling & Nutrition – Guidance for Industry: Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling, Nutrient Content Claims, Health Claims; Small Entity Compliance Guide". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. August 2003. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Federal Register – 68 FR 41433 11 July 2003: Food Labeling: Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling, Nutrient Content Claims, and Health Claims

|

Types of lipids

| |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Geometry | |

| Eicosanoids | |

| Fatty acids | |

| Glycerides | |

| Phospholipids | |

| Sphingolipids | |

| Steroids | |

|

Cardiovascular disease (vessels)

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arteries, arterioles and capillaries |

|||||||||

| Veins |

|

||||||||

| Arteries or veins | |||||||||

| Blood pressure |

|

||||||||