Human overpopulation

Human overpopulation (or human population overshoot) is the hypothetical state in which human populations can become too large to be sustained by their environment or resources in the long term. The topic is usually discussed in the context of world population, though it may concern individual nations, regions, and cities.

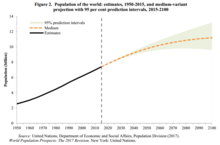

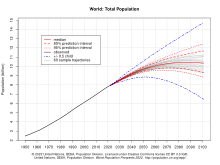

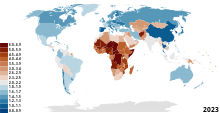

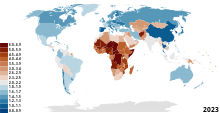

Since 1804, the global human population has increased from 1 billion to 8 billion due to medical advancements and improved agricultural productivity. According to the most recent United Nations' projections, "[t]he global population is expected to reach 9.7 billion in 2050 and 10.4 billion in 2100 [assuming] a decline of fertility for countries where large families are still prevalent." Those concerned by this trend argue that they result in levels of resource consumption and pollution which exceed the environment's carrying capacity, leading to population overshoot. The population overshoot hypothesis is often discussed in relation to other population concerns such as population momentum, biodiversity loss,hunger and malnutrition,resource depletion, and the overall human impact on the environment.

Early discussions of overpopulation in English were spurred by the work of Thomas Malthus. Discussions of overpopulation follow a similar line of inquiry as Malthusianism and its Malthusian catastrophe, a hypothetical event where population exceeds agricultural capacity, causing famine or war over resources, resulting in poverty and depopulation. More recent discussion of overpopulation was popularized by Paul Ehrlich in his 1968 book The Population Bomb and subsequent writings. Ehrlich described overpopulation as a function of overconsumption, arguing that overpopulation should be defined by a population being unable to sustain itself without depleting non-renewable resources.

Overview

Modern proponents of the concept have suggested that overpopulation, population growth and overconsumption are interdependent and collectively are the primary drivers of human-caused environmental problems such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Many scientists have expressed concern about population growth, and argue that creating sustainable societies will require decreasing the current global population. Advocates have suggested implementation of population planning strategies to reach a proposed sustainable population.

Overpopulation hypotheses are controversial, with many demographers and environmentalists disputing the core premise that the world cannot sustain the current trajectory of human population. Additionally, many economists and historians have noted that sustained shortages and famines have historically been caused by war, price controls, political instability, and repressive political regimes (often employing central planning) rather than overpopulation, and that population growth historically has led to greater technological development and advancement of scientific knowledge that has enabled the engineering of substitute goods and technology that better conserves and more efficiently uses natural resources, produces greater agricultural output with less land and less water, and addresses human impacts on the environment due to there being greater numbers of scientists, engineers, and inventors and subsequent generations of scientists overturning scientific paradigms maintained by previous generations of scientists. Instead, social scientists argue that disputes between themselves and biologists about human overpopulation are over the appropriateness of definitions being used (and often devolve into social scientists and biologists simply talking past each other).

Annual world population growth peaked at 2.1% in 1968, has since dropped to 1.1%, and could drop even further to 0.1% by 2100. Based on this, the United Nations projects the world population, which is 7.8 billion as of 2020, to level out around 2100 at 10.9 billion with other models proposing similar stabilization before or after 2100. Some experts believe that a combination of factors (including technological and social change) would allow global resources to meet this increased demand, avoiding global overpopulation. Additionally, some critics argue dismiss the idea of human overpopulation as a science myth connected to attempts to blame environmental issues on overpopulation oversimplify complex social or economic systems, or place blame on developing countries and poor populations—reinscribing colonial or racist assumptions and leading to discriminatory policy. These critics often suggest overconsumption should be treated as an issue separate from population growth.

History of world population

World population has been rising continuously since the end of the Black Death, around the year 1350. The fastest doubling of the world population happened between 1950 and 1986: a doubling from 2.5 to 5 billion people in 37 years, mainly due to medical advancements and increases in agricultural productivity. Due to its impact on the human ability to grow food, the Haber process enabled the global population to increase from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.7 billion by November 2018 and, according to the United Nationsanalyzed billion as of November 2022. Some researchers have analyzed this growth in population like other animal populations, human populations predictably grow and shrink according to their available food supply as per the Lotka–Volterra equations, including agronomist and insect ecologist David Pimentel, behavioral scientist Russell Hopfenberg, and anthropologist Virginia Abernethy.

| Year | 1806 | 1850 | 1900 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billions | 1.01 | 1.28 | 1.65 | 2.33 | 2.53 | 3.03 | 3.68 | 4.43 | 5.28 | 6.11 | 6.92 | 7.76 |

World population has gone through a number of periods of growth since the dawn of civilization in the Holocene period, around 10,000 BCE. The beginning of civilization roughly coincides with the receding of glacial ice following the end of the Last Glacial Period. Farming allowed for the growth of populations in many parts of the world, including Europe, the Americas and China through the 1600s, occasionally disrupted by plagues or other crises. For example, the Black Death is thought to have reduced the world's population, then at an estimated 450 million in 1350, to between 350 and 375 million by 1400.

After the start of the Industrial Revolution, during the 18th century, the rate of population growth began to increase. By the end of the century, the world's population was estimated at just under 1 billion. At the turn of the 20th century, the world's population was roughly 1.6 billion. By 1940, this figure had increased to 2.3 billion. Even more dramatic growth beginning in 1950 (above 1.8% per year) coincided with greatly increased food production as a result of the industrialization of agriculture brought about by the Green Revolution. The rate of human population growth peaked in 1964, at about 2.1% per year. Recent additions of a billion humans happened very quickly: 33 years to reach three billion in 1960, 14 years for four billion in 1974, 13 years for five billion in 1987, 12 years for six billion in 1999, 11 years for seven billion in 2010, and 12 years for 8 billion toward the end of 2022.

Future projections

| Continent | Projected 2050 population

by UN in 2017 |

|---|---|

| Africa | 2.5 billion |

| Asia | 5.5 billion |

| Europe | 716 million |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 780 million |

| North America | 435 million |

Population projections are attempts to show how the human population might change in the future. These projections help to forecast the population's impact on this planet and humanity's future well-being. Models of population growth take trends in human development, and apply projections into the future to understand how they will affect fertility and mortality, and thus population growth.

The most recent report from the United Nations Population Division issued in 2022 (see chart) projects that global population will peak around the year 2086 at about 10.4 billion, and then start a slow decline (the median line on the chart). As with earlier projections, this version assumes that the global average fertility rate will continue to fall, but even further from 2.5 births per woman during the 2015–2020 period to 1.8 by the year 2100.

However, other estimates predict additional downward pressure on fertility (such as more education and family planning) which could result in peak population during the 2060–2070 period rather than later.

According to the UN, of the predicted growth in world population between 2020 and 2050, all of that change will come from less developed countries, and more than half will come from just 8 African countries. It is predicted that the population of sub-Saharan Africa will double by 2050. The Pew Research Center predicts that 50% of births in the year 2100 will be in Africa.

As an example of uneven prospects, the UN projects that Nigeria will gain about 340 million people, about the present population of the US, to become the 3rd most populous country, and China will lose almost half of its population.

History of overpopulation hypotheses

Historical use

Concerns about population size or density have a long history: Tertullian, a resident of the city of Carthage in the second century CE, criticized population at the time: "Our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly support us... In very deed, pestilence, and famine, and wars, and earthquakes have to be regarded as a remedy for nations, as the means of pruning the luxuriance of the human race." Despite those concerns, scholars have not found historic societies that have collapsed because of overpopulation or overconsumption.

By the early 19th century, intellectuals such as Thomas Malthus predicted that humankind would outgrow its available resources because a finite amount of land would be incapable of supporting a population with limitless potential for increase. During the 19th century, Malthus' work, particularly An Essay on the Principle of Population, was often interpreted in a way that blamed the poor alone for their condition and helping them was said to worsen conditions in the long run. This resulted, for example, in the English poor laws of 1834 and a hesitating response to the Irish Great Famine of 1845–52.

The first World Population Conference was held in 1927 in Geneva, organized by the League of Nations and Margaret Sanger.

Contemporary use

Paul R. Ehrlich's book The Population Bomb became a bestseller upon its release in 1968 and created renewed interest in overpopulation. The book predicted population growth would lead to famine, societal collapse, and other social, environmental and economic strife in the coming decades, and advocated for policies to curb it. The Club of Rome published the influential report The Limits to Growth in 1972, which used computer modeling to similarly argue that continued population growth trends would lead to global system collapse. The idea of overpopulation was also a topic of some works of English-language science fiction and dystopian fiction during the latter part of the 1960s. The United Nations held the first of three World Population Conferences in 1974.Human population and family planning policies were adopted by some nations in the late 20th century in an effort to curb population growth, including in China and India.Albert Allen Bartlett gave more than 1,742 lectures on the threat of exponential population growth starting in 1969.

However, many predictions of overpopulation during the 20th century did not materialize. In The Population Bomb, Ehrlich stated, "In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now," with later editions changing to "in the 1980s". Despite admitting some of his earlier predictions did not come to pass, Ehrlich continues to advocate that overpopulation is a major issue.

As the profile of environmental issues facing humanity increased during the end of the 20th and the early 21st centuries, some have looked to population growth as a root cause. In the 2000s, E. O. Wilson and Ron Nielsen discussed overpopulation as a threat to the quality of human life. In 2011, Pentti Linkola argued that human overpopulation represents a threat to Earth's biosphere. A 2015 survey from Pew Research Center reports that 82% of scientists associated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science were concerned about population growth. In 2017, more than one-third of 50 Nobel prize-winning scientists surveyed by the Times Higher Education at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings said that human overpopulation and environmental degradation are the two greatest threats facing mankind. In November that same year, the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice, signed by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries, indicated that rapid human population growth is "a primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats." Ehlrich and other scientists at a conference in the Vatican on contemporary species extinction linked the issue to population growth in 2017, and advocated for human population control, which attracted controversy from the Catholic church. In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss."

In 2020, a quote from David Attenborough about how humans have "overrun the planet" was shared widely online and became his most popular comment on the internet.

Key arguments

Overconsumption

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and Global Footprint Network have argued that the annual biocapacity of Earth has exceeded, as measured using the ecological footprint. In 2006, WWF's Living Planet Report stated that in order for all humans to live with the current consumption patterns of Europeans, we would be spending three times more than what the planet can renew. According to these calculations, humanity as a whole was using by 2006 40% more than what Earth can regenerate. Another study by the WWF in 2014 found that it would take the equivalent of 1.5 Earths of bio-capacity to meet humanity's current levels of consumption. However, Roger Martin of Population Matters states the view: "the poor want to get rich, and I want them to get rich," with a later addition, "of course we have to change consumption habits,... but we've also got to stabilize our numbers".

Critics have questioned the simplifications and statistical methods used in calculating ecological footprints. Therefore, Global Footprint Network and its partner organizations have engaged with national governments and international agencies to test the results—reviews have been produced by France, Germany, the European Commission, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Japan and the United Arab Emirates. Some point out that a more refined method of assessing Ecological Footprint is to designate sustainable versus non-sustainable categories of consumption.

Carrying capacity

Attempts have been made to estimate the world's carrying capacity for humans; the maximum population the world can host. A 2004 meta-analysis of 69 such studies from 1694 until 2001 found the average predicted maximum number of people the Earth would ever have was 7.7 billion people, with lower and upper meta-bounds at 0.65 and 98 billion people, respectively. They conclude: "recent predictions of stabilized world population levels for 2050 exceed several of our meta-estimates of a world population limit".

A 2012 United Nations report summarized 65 different estimated maximum sustainable population sizes and the most common estimate was 8 billion. Advocates of reduced population often put forward much lower numbers. Paul R. Ehrlich stated in 2018 that the optimum population is between 1.5 and 2 billion. In 2022 Erhlich and other contributors to the "Scientists' warning on population", including Eileen Crist, William J. Ripple, William E. Rees and Christopher Wolf, stated that environmental analysts put the sustainable level of human population at between 2 and 4 billion people. Geographer Chris Tucker estimates that 3 billion is a sustainable number.

Critics of overpopulation criticize the basic assumptions associated with these estimates. For example, associate professor of gender and sexuality Jade Sasser believes that calculating a maximum of number of humanity is unethical claiming that only some, mostly European former colonial powers, are mostly responsible for unsustainably using up Earth's resources.

Proposed impacts

Poverty, and infant and child mortality

Although proponents of human overpopulation have expressed concern that growing population will lead to an increase in global poverty and infant mortality, both indicators have declined over the last 200 years of population growth.

Environmental impacts

A number of scientists have argued that human impacts on the environment and accompanying increase in resource consumption threatens the world's ecosystems and the survival of human civilization. The InterAcademy Panel Statement on Population Growth, which was ratified by 58 member national academies in 1994, states that "unprecedented" population growth aggravates many environmental problems, including rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, global warming, and pollution. Indeed, some analysts claim that overpopulation's most serious impact is its effect on the environment. Some scientists suggest that the overall human impact on the environment during the Great Acceleration, particularly due to human population size and growth, economic growth, overconsumption, pollution, and proliferation of technology, has pushed the planet into a new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.

Some studies and commentary link population growth with climate change. Critics have stated that population growth alone may have less influence on climate change than other factors, such as greenhouse gas emissions per capita. The global consumption of meat is projected to rise by as much as 76% by 2050 as the global population increases, with this projected to have further environmental impacts such as biodiversity loss and increased greenhouse gas emissions. A July 2017 study published in Environmental Research Letters argued that the most significant way individuals could mitigate their own carbon footprint is to have fewer children, followed by living without a vehicle, forgoing air travel, and adopting a plant-based diet. However, even in countries which have both large population growth and major ecological problems, it is not necessarily true that curbing the population growth will make a major contribution towards resolving all environmental problems that can be solved simply with an environmentalist policy approach.

Continued population growth and overconsumption, particularly by the wealthy, have been posited as key drivers of biodiversity loss and contemporary species extinction, with some researchers and environmentalists specifically suggesting this indicates a human overpopulation scenario. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, released by IPBES in 2019, states that human population growth is a factor in biodiversity loss. IGI Global has uncovered the growth of the human population caused encroachment in wild habitats which have led to their destruction, "posing a potential threat to biodiversity components".

Some scientists and environmentalists, including Jared Diamond,E. O. Wilson, Jane Goodall and David Attenborough, contend that population growth is devastating to biodiversity. Wilson for example, has expressed concern when Homo sapiens reached a population of six billion their biomass exceeded that of any other large land dwelling animal species that had ever existed by over 100 times.Inger Andersen, the executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, stated in December 2022 as the human population reached a milestone of 8 billion and as delegates were meeting for the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference, that "we need to understand that the more people there are, the more we put the Earth under heavy pressure. As far as biodiversity is concerned, we are at war with nature."

Human overpopulation and continued population growth are also considered by some, including animal rights attorney Doris Lin and philosopher Steven Best, to be an animal rights issue, as more human activity means the destruction of animal habitats and more direct killing of animals.

Resource depletion

Some commentary has attributed depletion of non-renewable resources, such as land, food and water, to overpopulation and suggested it could lead to a diminished quality of human life. Ecologist David Pimentel was one such proponent, saying "with the imbalance growing between population numbers and vital life sustaining resources, humans must actively conserve cropland, freshwater, energy, and biological resources. There is a need to develop renewable energy resources. Humans everywhere must understand that rapid population growth damages the Earth's resources and diminishes human well-being."

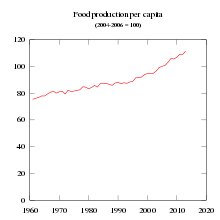

Although food shortages have been warned as a consequence of overpopulation, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, global food production exceeds increasing demand from global population growth. Food insecurity in some regions is attributable to the globally unequal distribution of food supplies.

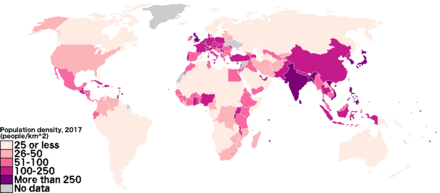

The notion that space is limited has been decried by skeptics, who point out that the Earth's population of roughly 6.8 billion people could comfortably be housed an area comparable in size to the state of Texas in the United States (about 269,000 square miles or 696,706.80 square kilometres). Critics and agricultural experts suggest changes to policies relating to land use or agriculture to make them more efficient would be more likely to resolve land issues and pressures on the environment than focusing on reducing population alone.

Water scarcity, which threatens agricultural productivity, represents a global issue that some have linked to population growth. Colin Butler wrote in The Lancet in 1994 that overpopulation also has economic consequences for certain countries due to resource use.

Political systems and social conflict

It was speculated by Aldous Huxley in 1958 that democracy is threatened by overpopulation, and could give rise to totalitarian style governments. Physics professor Albert Allen Bartlett at the University of Colorado Boulder warned in 2000 that overpopulation and the development of technology are the two major causes of the diminution of democracy. However, over the last 200 years of population growth, the actual level of personal freedom has increased rather than declined.John Harte has argued population growth is a factor in numerous social issues, including unemployment, overcrowding, bad governance and decaying infrastructure.Daron Acemoglu and others suggested in a 2017 paper that since the Second World War, countries with higher population growth rates experienced the most social conflict.

Some advocates have suggested societal problems such as hunger and mass unemployment are linked to overpopulation.

According to anthropologist Jason Hickel, the global capitalist system creates pressures for population growth: "more people means more labour, cheaper labour, and more consumers." Hickel has however argued that the cause of negative environmental impacts is resource extraction by wealthy countries.

Epidemics and pandemics

A 2021 article in Ethics, Medicine and Public Health argued in light of the COVID-19 pandemic that epidemics and pandemics were made more likely by overpopulation, globalization, urbanization and encroachment into natural habitats.

They both play a significant role impact on human populations, including widespread illness, death, and social disruption. While they can leave to a temporarily loss of population but is followed by significant loss and suffering. These events is not the sole reason for overpopulation but lack of access to family planning and reproductive contraptions, poverty and resource depletion.

Proposed solutions and mitigation measures

Several strategies have been proposed to mitigate overpopulation.

Population planning

Several scientists (including Paul Ehrlich, Gretchen Daily and Tim Flannery) proposed that humanity should work at stabilizing its absolute numbers, as a starting point towards beginning the process of reducing the total numbers. They suggested several possible approaches, including:

- Improved access to contraception and sex education

- Reducing infant mortality, so that parents do not need to have many children to ensure at least some survive to adulthood.

- Improving the status of women in order to facilitate a departure from traditional sexual division of labour.

- Family planning

- Creating small family "role models"

- Secular cultures and societies.

There is good evidence from many parts of the world that when women and couples have the freedom to choose how many children to have, they tend to have smaller families.

Some scientists, such as Corey Bradshaw and Barry Brook, suggest that, given the "inexorable demographic momentum of the global human population," sustainability can be achieved more rapidly with a short term focus on technological and social innovations, along with reducing consumption rates, while treating population planning as a long-term goal.

However, most scientists believe that achieving genuine sustainability is a long-term project, and that addressing population and consumption levels are both essential to achieving it.

In 1992, more than 1700 scientists from around the world signed onto a "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity," including a majority of the living Nobel prize-winners in the sciences. "The earth is finite," they wrote. "Its ability to absorb wastes and destructive effluent is finite. Its ability to provide food and energy is finite. Its ability to provide for growing numbers of people is finite. And we are fast approaching many of the earth's limits." The warning noted:

Pressures resulting from unrestrained population growth put demands on the natural world that can overwhelm any efforts to achieve a sustainable future. If we are to halt the destruction of our environment, we must accept limits to that growth.

Two of the five areas where the signatories requested immediate action were "stabilize population" and "ensure sexual equality, and guarantee women control over their own reproductive decisions."

In a follow-up message 25 years later, William Ripple and colleagues issued the "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice." This time more than 15,000 scientists from around the world signed on. "We are jeopardizing our future by not reining in our intense but geographically and demographically uneven material consumption and by not perceiving continued rapid population growth as a primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats," they wrote. "By failing to adequately limit population growth, reassess the role of an economy rooted in growth, reduce greenhouse gases, incentivize renewable energy, protect habitat, restore ecosystems, curb pollution, halt defaunation, and constrain invasive alien species, humanity is not taking the urgent steps needed to safeguard our imperilled biosphere." This second scientists’ warning urged attention to both excessive consumption and continued population growth. Like its predecessor, it did not specify a definite global human carrying capacity. But its call to action included "estimating a scientifically defensible, sustainable human population size for the long term while rallying nations and leaders to support that vital goal."

Subsequent scientists' calls to action have also included calls for population planning. The 2020 "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency" stated: "Economic and population growth are among the most important drivers of increases in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion." "Therefore," the study noted: "we need bold and drastic transformations regarding economic and population policies." "The world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced," it concluded, implying that humanity is overpopulated given current and expected levels of resource use and waste generation.

A follow-up scientists’ warning on climate change in 2021 reiterated the need to plan and limit human numbers to achieve sustainability, proposing as a goal "stabilizing and gradually reducing the [global] population by providing voluntary family planning and supporting education and rights for all girls and young women, which has been proven to lower fertility rates."

Family planning

Education and empowerment of women and giving access to family planning and contraception have a demonstrated impact on reducing birthrates. Many studies conclude that educating girls reduces the number of children they have. One option according to some activists is to focus on education about family planning and birth control methods, and to make birth-control devices like condoms, contraceptive pills and intrauterine devices easily available. Worldwide, nearly 40% of pregnancies are unintended (some 80 million unintended pregnancies each year). An estimated 350 million women in the poorest countries of the world either did not want their last child, do not want another child or want to space their pregnancies, but they lack access to information, affordable means and services to determine the size and spacing of their families. In the developing world, some 514,000 women die annually of complications from pregnancy and abortion, with 86% of these deaths occurring in the sub-Saharan Africa region and South Asia. Additionally, 8 million infants die, many because of malnutrition or preventable diseases, especially from lack of access to clean drinking water.

Women's rights and their reproductive rights in particular are issues regarded to have vital importance in the debate. Anthropologist Jason Hickel asserts that a nation's population growth rapidly declines - even within a single generation - when policies relating to women's health and reproductive rights, children's health (to ensure parents they will survive to adulthood), and expanding education and economic opportunities for girls and women are implemented.

A 2020 paper by William J. Ripple and other scientists argued in favor of population policies that could advance social justice (such as by abolishing child marriage, expanding family planning services and reforms that improve education for women and girls) and at the same time mitigate the impact of population growth on climate change and biodiversity loss. In a 2022 warning on population published by Science of the Total Environment, Ripple, Ehrlich and other scientists appealed to families around the world to have no more than one child and also urged policy-makers to improve education for young females and provide high-quality family-planning services.

Extraterrestrial settlement

An argument for space colonization is to mitigate proposed impacts of overpopulation of Earth, such as resource depletion. If the resources of space were opened to use and viable life-supporting habitats were built, Earth would no longer define the limitations of growth. Although many of Earth's resources are non-renewable, off-planet colonies could satisfy the majority of the planet's resource requirements. With the availability of extraterrestrial resources, demand on terrestrial ones would decline. Proponents of this idea include Stephen Hawking and Gerard K. O'Neill.

Others including cosmologist Carl Sagan and science fiction writers Arthur C. Clarke, and Isaac Asimov, have argued that shipping any excess population into space is not a viable solution to human overpopulation. According to Clarke, "the population battle must be fought or won here on Earth". The problem for these authors is not the lack of resources in space (as shown in books such as Mining the Sky), but the physical impracticality of shipping vast numbers of people into space to "solve" overpopulation on Earth.Urbanization

Despite the increase in population density within cities (and the emergence of megacities), UN Habitat Data Corp. states in its reports that urbanization may be the best compromise in the face of global population growth. Cities concentrate human activity within limited areas, limiting the breadth of environmental damage. UN Habitat says this is only possible if urban planning is significantly improved.

Paul R. Ehrlich proposed in The Population Bomb that rhetoric supporting the increase of city density is a means of avoiding dealing with what he views as the root problem of overpopulation and has been promoted by what he views as the same interests that have allegedly profited from population increase (such as property developers, the banking system which invests in property development, industry, and municipal councils). Subsequent authors point to growth economics as driving governments seek city growth and expansion at any cost, disregarding the impact it might have on the environment.

Criticism

The concept of human overpopulation, and its attribution as a cause of environmental issues, are controversial.

Some critics, including Nicholas Eberstadt, Fred Pearce, Dominic Lawson and Betsy Hartmann, refer to overpopulation as a myth. Predicted exponential population growth or any "population explosion" did not materialise; instead, population growth slowed. Critics suggest that enough resources are available to support projected population growth, and that human impacts on the environment are not attributable to overpopulation.

According to libertarian think tank the Fraser Institute, both the idea of overpopulation and the alleged depletion of resources are myths; most resources are now more abundant than a few decades ago, thanks to technological progress. The institute also questions the sincerity of advocates of population control in poor countries.

Nicholas Eberstadt, a political economist, has criticised the idea of overpopulation, saying that "overpopulation is not really overpopulation. It is a question of poverty".

A 2020 study in The Lancet concluded that "continued trends in female educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in fertility and slow population growth", with projections suggesting world population would peak at 9.73 billion in 2064 and fall by 2100. Media commentary interpreted this as suggesting overconsumption represents a greater environmental threat as an overpopulation scenario may never occur.

Some human population planning strategies advocated by proponents of overpopulation are controversial for ethical reasons. Those concerned with overpopulation, including Paul Ehrlich, have been accused of influencing human rights abuses including forced sterilisation policies in India and under China's one-child policy, as well as mandatory or coercive birth control measures taken in other countries.

Women's rights

Influential advocates such as Betsy Hartmann consider the "myth of overpopulation" to be destructive as it "prevents constructive thinking and action on reproductive rights," which acutely affects women and communities of women in poverty. The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) defines reproductive rights as "the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing, and timing of their children and to have the information to do so." This oversimplification of human overpopulation leads individuals to believe there are simple solutions and the creation of population policies that limit reproductive rights.

In response, philosopher Tim Meijers asks the question: "To what extent is it fair to require people to refrain from procreating as part of a strategy to make the world more sustainable?" Meijers rejects the idea that the right to reproduce can be unlimited, since this would not be universalizable: "in a world in which everybody had many children, extreme scarcity would arise and stable institutions could prove unsustainable. This would lead to violation of (rather uncontroversial) rights such as the right to life and to health and subsistence." In the actual world today, excessive procreation could also undermine our descendants' right to have children, since people are likely to refrain (and perhaps should refrain) from bringing children into an insecure and dangerous world. Meijers, Sarah Conly, Diana Coole, and other ethicists conclude that people have a right to found a family, but not to unlimited numbers of children.

Coercive population control policies

Ehrlich advocated in The Population Bomb that "various forms of coercion", such as removing tax benefits for having additional children, be used in cases when voluntary population planning policies fail. Some nations, like China, have used strict or coercive measures such as the one-child policy to reduce birth rates.Compulsory or semi-compulsory sterilization, such as for token material compensation or easing of penalties, has also been implemented in many countries as a form of population control.

Another choice-based approach is financial compensation or other benefits by the state offered to people who voluntarily undergo sterilization. Such policies have been introduced by the government of India.

The Indian government of Narendra Modi introduced population policies in the 21st century, including offering incentives for sterilization by citing the risks of a "population explosion" although demographers have criticized that basis, with India thought to be undergoing demographic transition and its fertility rate falling. The policies have also received criticism from human and women's rights groups.

Racism

The concept of human overpopulation has been criticized by some scholars and environmentalists as being racist and having roots in colonialism and white supremacy, since control and reduction of human population is often focused on the global south, instead of on overconsumption and the global north, where it occurs.Paul Ehrlich's Population Bomb begins with him describing first knowing the "feel of overpopulation" from a visit to Delhi, which some critics have accused of having racial undertones.George Monbiot has said "when affluent white people wrongly transfer the blame for their environmental impacts on to the birthrate of much poorer brown and black people, their finger-pointing reinforces [Great Replacement and white genocide conspiracy] narratives. It is inherently racist." Overpopulation is a common component of ecofascist ideology.

Scholar Heather Alberro rejects the overpopulation argument, stating that the human population growth is rapidly slowing down, the underlying problem is not the number of people, but how resources are distributed and that the idea of overpopulation could fuel a racist backlash against the population of poor countries.

In response, population activists argue that overpopulation is a problem in both rich and poor countries, and arguably a worse problem in rich countries, where residents’ higher per capita consumption ratchets up the impacts of their excessive numbers. Feminist scholar Donna Haraway notes that a commitment to enlarging the moral community to include nonhuman beings logically entails people’s willingness to limit their numbers and make room for them. Ecological economists like Herman Daly and Joshua Farley believe that reducing populations will make it easier to achieve steady-state economies that decrease total consumption and pollution to manageable levels. Finally, as Karin Kuhlemann observes, "that a population's size is stable in no way entails sustainability. It may be sustainable, or it may be far too large."

According to the writer and journalist Krithika Varagur, myths and misinformation about overpopulation of Rohingya people in Myanmar is thought to have driven their genocide in the 2010s.

Advocacy organizations

The following organizations advocate for a limit to human population growth, although their focus may be on related issues such as environmental protection:

- Global Footprint Network, a coalition of NGOs that calculates the annual Earth Overshoot Day

- Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere (MAHB)

- Negative Population Growth

- Population Matters

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement

- Population Media Center

- Church of Euthanasia

Organization advocate against limits to human population growth.

See also

- Demographic trap

- Demographic transition

- The Limits to Growth

- Human population planning

- Malthusian catastrophe

- Overshoot (population)

- Planetary boundaries

- Antinatalism

- Overpopulation in domestic pets

Documentary and art

- Bundled references

Further reading

Matthew Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. Harvard University Press, 2010. ISBN 9780674034600

- David Foreman, Man Swarm: How Overpopulation is Killing the Wild World. Livetrue Books, 2015. ISBN 978-0986383205

- Karen Shragg, Move Upstream: A Call to Solve Overpopulation. ISBN 978-0988493834 (published November 2015). Discussion of the book by the author, March 2017 (video, 91 minutes).

- Alan Weisman. Countdown: Our Last, Best Hope for a Future on Earth? Little, Brown and Company, (2013) ISBN 0316097756

- Thomas Robertson, The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism (2012), Rutgers University Press

- J.R. McNeill, Peter Engelke, The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945 (2016)