Lymphatic filariasis

| Lymphatic filariasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Elephantiasis tropica, elephantiasis arabum |

| |

| Elephantiasis of the legs due to filariasis. | |

| Specialty |

Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | None, severe swelling of the arms, legs, breasts, or genitals |

| Causes | Filarial worms spread by mosquitos |

| Diagnostic method | Microscopic examination of blood |

| Prevention | Bed nets, mass deworming |

| Medication | Albendazole with ivermectin or diethylcarbamazine |

| Frequency | 40 million (2022) |

Lymphatic filariasis is a human disease caused by parasitic worms known as filarial worms. Usually acquired in childhood, it is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide. While most cases have no symptoms, some people develop a syndrome called elephantiasis, which is marked by severe swelling in the arms, legs, breasts, or genitals. The skin may become thicker as well, and the condition may become painful. Affected people are often unable to work and are often shunned or rejected by others because of their disfigurement and disability.

It is the first of the mosquito-borne diseases to have been identified. The worms are spread by the bites of infected mosquitoes. Three types of worms are known to cause the disease: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori, with Wuchereria bancrofti being the most common. These worms damage the lymphatic system. The disease is diagnosed by microscopic examination of blood collected during the night. The blood is typically examined as a smear after being stained with Giemsa stain. Testing the blood for antibodies against the disease may also permit diagnosis. Other roundworms from the same family are responsible for river blindness.

Prevention can be achieved by treating entire groups in which the disease exists, known as mass deworming. This is done every year for about six years, in an effort to rid a population of the disease entirely.Medications used include antiparasitics such as albendazole with ivermectin, or albendazole with diethylcarbamazine. The medications do not kill the adult worms but prevent further spread of the disease until the worms die on their own. Efforts to prevent mosquito bites are also recommended, including reducing the number of mosquitoes and promoting the use of bed nets.

As of 2022, about 40 million people were infected, and about 863 million people were at risk of the disease in 47 countries. It is most common in tropical Africa and Asia. Lymphatic filariasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease and one of the four main worm infections. The impact of the disease results in economic losses of billions of dollars a year.

Signs and symptoms

People affected by lymphatic filariasis often experience adverse immunological reactions to the microfilariae as well as the adult worms. Filariasis may also be associated with ascites following the severe inflammatory reaction in the lymphatics.

Elephantiasis (or "elephantiasis tropica"), is a dramatic sign of the advanced stage of lymphatic filariasis. Elephantiasis is an advanced stage of lymphedema, characterized by thickening of the skin and underlying tissues of the lower half of the body, causing it to look like that of an elephant. It occurs as a result of the adult worms lodging in the lymphatic system and obstructing the flow of lymph. Different species of filarial worms tend to affect different parts of the body: Wuchereria bancrofti can affect the arms, breasts, legs, scrotum, and vulva (causing hydrocele formation), while Brugia timori rarely affects the genitals.

Causes

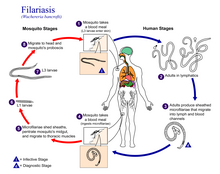

Three species of filarial roundworms, all from the Onchocercidae family, cause human lymphatic filariasis: Wuchereria bancrofti (the most common causative species), Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. The filarial roundworms are transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito of genera Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, or Mansonia. The mosquito deposits the L3 (infective stage) larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound. From there, the larvae enter the lymphatic vessels and develop into adults. The larvae take up residence in the lymphatic vessels and the lung tissue, hindering respiration and causing chest pain as the disease progresses. This disease can be confused with tuberculosis,asthma, or coughs related to roundworms.

The disease itself is a result of a complex interplay between several factors: the worm, the endosymbiotic Wolbachia bacteria within the worm, the host's immune response, and the numerous opportunistic infections and disorders that arise. The adult worms live in the human lymphatic system and obstruct the flow of lymph throughout the body; this results in chronic lymphedema, most often noted in the lower torso (typically in the legs and genitals).

Diagnosis

The preferred method for diagnosing lymphatic filariasis is by finding the microfilariae via microscopic examination of the blood. The blood sample is typically in the form of a thick smear, stained with Giemsa stain. Technicians analyzing the blood smear must be able to distinguish between W. bancrofti and other parasites potentially present. A blood smear is a simple and fairly accurate diagnostic tool, provided the blood sample is taken during when the microfilariae are in the peripheral circulation. Because the microfilariae only circulate in the blood at night, the blood specimen must be collected at night.

It is often difficult or impossible to detect the causative organism in the peripheral blood, even in advanced cases. In such cases, testing the blood serum for antibodies against the disease may also be used. A polymerase chain reaction test can also be performed to detect a minute fraction, as little as 1 pg, of filarial DNA. Dead, calcified worms can be detected by X-ray examinations. Ultrasonography can also be used to detect the movements and noises caused by the movement of adult worms.

Differential diagnosis

Lymphatic filariasis may be confused with podoconiosis (also known as nonfilarial elephantiasis), a non-infectious disease caused by exposure of bare feet to irritant alkaline clay soils. Podoconiosis however typically affects the legs bilaterally, while filariasis is generally unilateral. Also, podoconiosis very rarely affects the groin while filariasis frequently involves the groin. Geographical location may also help to distinguish between these two diseases: podoconiosis is typically found in higher altitude areas with high seasonal rainfall, while filariasis is common in low-lying areas where mosquitos are prevalent.

Prevention

Protecting against mosquito bites in endemic regions is crucial to the prevention of lymphatic filariasis. Insect repellents and mosquito nets (especially when treated with an insecticide such as deltamethrin or permethrin) have been demonstrated to reduce the transmission of lymphatic filariasis.

Worldwide eradication of lymphatic filariasis is the definitive goal. This is considered to be achievable since the disease has no known animal reservoir. The World Health Organization (WHO) is coordinating the global effort to eradicate filariasis. The mainstay of this program is mass deworming of entire populations of people who are at risk with antifilarial drugs. The specific treatment depends on the co-endemicity of lymphatic filariasis with other filarial diseases. For example, in locations without onchocerciasis, ivermectin is given along with albendazole and diethylcarbamazine. In locations where onchocerciasis is co-endemic, ivermectin and albendazole are given. Because the parasite requires a human host to reproduce, consistent treatment of at-risk populations (annually for a duration of four to six years) is expected to break the cycle of transmission and cause the extinction of the causative organisms.

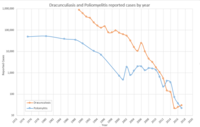

In 2011, Sri Lanka was certified by the WHO as having eradicated lymphatic filariasis. In July 2017, the WHO announced that the disease had been eliminated in Tonga. Elimination of the disease has also occurred in Cambodia, China, Cook Islands, Egypt, Kiribati, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Niue, Palau, South Korea, Thailand, Vanuatu, Vietnam and Wallis and Futuna. In 2020, the WHO announced that the 2030 targets for this program are that lymphatic filariasis will have been eliminated in 80% of endemic countries.

A vaccine is not yet available, but in 2013, the University of Illinois College of Medicine was reporting 95% efficacy in testing against B. malayi in mice.

Treatment

Treatment of lymphatic filariasis depends in part on the geographic location of the area of the world in which the disease was acquired, but almost always involves the use of anthelmintic agents. In sub-Saharan Africa, albendazole is used along with ivermectin to treat the disease, whereas elsewhere in the world, albendazole is used with diethylcarbamazine.

Wolbachia are endosymbiotic bacteria that live inside the gut of the parasites responsible for lymphatic filariasis, and provide nutrients necessary for their survival. Doxycycline kills these bacteria, which in turn prevents the maturation of microfilariae into adults. It also shortens the lifespan of the adult worms, causing them to die within 1 to 2 years instead of their normal 10 to 14-year lifespan. Doxycycline is effective in treating lymphatic filariasis. Limitations of this antibiotic protocol include that it requires 4 to 6 weeks of treatment rather than the single dose of the anthelmintic agents, that doxycycline should not be used in young children and pregnant women, and that it is phototoxic.

Surgical treatment may be helpful in cases of scrotal elephantiasis and hydrocele. However, surgery is generally ineffective at correcting elephantiasis of the limbs.

Epidemiology

Lymphatic filariasis occurs in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, and certain Pacific Island nations. Elephantiasis caused by lymphatic filariasis is one of the most common causes of permanent disability in the world. As of 2018, 51 million people were infected with lymphatic filariasis and at least 863 million people in 50 countries were living in areas that require preventive chemotherapy to stop the spread of infection. By 2022, the prevalence had declined to somewhere around 40 million and the disease remains endemic in 47 countries. These improvements are a direct result of the WHO's Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis.

W. bancrofti is responsible for 90% of lymphatic filariasis. Brugia malayi causes most of the remainder of the cases, while Brugia timori is a rare cause.W. bancrofti largely affects areas across the broad equatorial belt (Africa, the Nile Delta, Turkey, India, the East Indies, Southeast Asia, Philippines, Oceanic Islands, and parts of South America). The mosquito vectors of W. bancrofti have a preference for human blood; humans are apparently the only animals naturally infected with W. bancrofti. No reservoir host is known.

In areas endemic for podoconiosis, prevalence can be 5% or higher. In communities where lymphatic filariasis is endemic, as many as 10% of women can be affected by swollen limbs, and 50% of men can develop mutilating genital symptoms.

History

There is evidence of Lymphatic filariasis cases dating back 4000 years. The ancient Vedic text, the Rig Veda, composed around 1500 BC - 1200 BC, makes a possible reference to elephantiasis. The 50th hymn of the 7th book of the Rigveda calls on the gods Mitra, Varuna and Agni for protection against "that which nests inside and swells". The author of the hymn implores the deities to not let the worm wound his foot. The disease is described as causing eruptions to appear on the ankles and the knees. Artifacts from ancient Egypt (2000 BC) and the Nok civilization in West Africa (500 BC) show possible elephantiasis symptoms. The first clear reference to the disease occurs in ancient Greek literature, wherein scholars differentiated the often similar symptoms of lymphatic filariasis from those of leprosy, describing leprosy as elephantiasis graecorum and lymphatic filariasis as elephantiasis arabum.

The first documentation of symptoms occurred in the 16th century, when Jan Huyghen van Linschoten wrote about the disease during the exploration of Goa. Similar symptoms were reported by subsequent explorers in areas of Asia and Africa, though an understanding of the disease did not begin to develop until centuries later.

The causative agents were first identified in the late 19th century. In 1866, Timothy Lewis, building on the work of Jean Nicolas Demarquay and Otto Henry Wucherer, made the connection between microfilariae and elephantiasis, establishing the course of research that would ultimately explain the disease. In 1876, Joseph Bancroft discovered the adult form of the worm. In 1877, the lifecycle involving an arthropod vector was theorized by Patrick Manson, who proceeded to demonstrate the presence of the worms in mosquitoes. Manson incorrectly hypothesized that the disease was transmitted through skin contact with water in which the mosquitoes had laid eggs. In 1900, George Carmichael Low determined the actual transmission method by discovering the presence of the worm in the proboscis of the mosquito vector.

Many people in Malabar, Nayars as well as Brahmans and their wives – in fact about a quarter or a fifth of the total population, including the people of the lowest castes – have very large legs, swollen to a great size; and they die of this, and it is an ugly thing to see. They say that this is due to the water through which they go, because the country is marshy. This is called pericaes in the native language, and all the swelling is the same from the knees downward, and they have no pain, nor do they take any notice of this infirmity.

— Portuguese diplomat Tomé Pires, Suma Oriental, 1512–1515.

Research directions

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) have developed a novel vaccine for the prevention of lymphatic filariasis. This vaccine has been shown to elicit strong, protective immune responses in mouse models of lymphatic filariasis infection. The immune response elicited by this vaccine has been demonstrated to be protective against both W. bancrofti and B. malayi infection in the mouse model and may prove useful in the human.

On 20 September 2007, geneticists published the first draft of the complete genome (genetic content) of Brugia malayi, one of the roundworms which causes lymphatic filariasis. This project had been started in 1994 and by 2000, 80% of the genome had been determined. Determining the content of the genes might lead to the development of new drugs and vaccines.

Veterinary disease

Onchocerca ochengi causes lymphatic filariasis in cattle.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Eradication of human diseases |

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eradication of agricultural diseases |

|

|||||||

| Eradication programs |

|

|||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||