Prostate-specific antigen

| KLK3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | KLK3, APS, KLK2A1, PSA, hK3, kallikrein related peptidase 3, Prostate Specific Antigen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 176820 MGI: 97320 HomoloGene: 68141 GeneCards: KLK3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

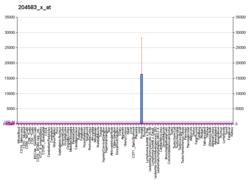

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA), also known as gamma-seminoprotein or kallikrein-3 (KLK3), P-30 antigen, is a glycoprotein enzyme encoded in humans by the KLK3 gene. PSA is a member of the kallikrein-related peptidase family and is secreted by the epithelial cells of the prostate gland.

PSA is produced for the ejaculate, where it liquefies semen in the seminal coagulum and allows sperm to swim freely. It is also believed to be instrumental in dissolving cervical mucus, allowing the entry of sperm into the uterus.

PSA is present in small quantities in the serum of men with healthy prostates, but is often elevated in the presence of prostate cancer or other prostate disorders. PSA is not uniquely an indicator of prostate cancer, but may also detect prostatitis or benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Medical Diagnostic Uses

Prostate cancer

Screening

Clinical practice guidelines for prostate cancer screening vary and are controversial, in part due to uncertainty as to whether the benefits of screening ultimately outweigh the risks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the PSA test for annual screening of prostate cancer in men of age 50 and older. The patient is required to be informed of the risks and benefits of PSA testing prior to performing the test.

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) as of 2018 does not mandate, nor advise for PSA test, but allows patients to decide based on their doctor's advice. The NHS does not offer general PSA screening, for similar reasons.

PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng/mL (nanograms per milliliter) are considered to be suspicious, and consideration should be given to confirming the abnormal PSA with a repeat test. If indicated, prostate biopsy is performed to obtain a tissue sample for histopathological analysis.

While PSA testing may help 1 in 1,000 avoid death due to prostate cancer, 4 to 5 in 1,000 would die from prostate cancer after 10 years even with screening. This means that PSA screening may reduce mortality from prostate cancer by up to 25%. Expected harms include anxiety for 100 – 120 receiving false positives, biopsy pain, and other complications from biopsy for false positive tests.

Use of PSA screening tests is also controversial due to questionable test accuracy. The screening can present abnormal results even when a man does not have cancer (known as a false-positive result), or normal results even when a man does have cancer (known as a false-negative result). False-positive test results can cause confusion and anxiety in men, and can lead to unnecessary prostate biopsies, a procedure which causes risk of pain, infection, and hemorrhage. False-negative results can give men a false sense of security, though they may actually have cancer.

Of those found to have prostate cancer, overtreatment is common because most cases of prostate cancer are not expected to cause any symptoms due to low rate of growth of the prostate tumor. Therefore, many will experience the side effects of treatment, such as for every 1000 men screened, 29 will experience erectile dysfunction, 18 will develop urinary incontinence, two will have serious cardiovascular events, one will develop pulmonary embolus or deep venous thrombosis, and one perioperative death. Since the expected harms relative to risk of death are perceived by patients as minimal, men found to have prostate cancer usually (up to 90% of cases) elect to receive treatment.

Risk stratification and staging

Men with prostate cancer may be characterized as low, intermediate, or high risk for having/developing metastatic disease or dying of prostate cancer. PSA level is one of three variables on which the risk stratification is based; the others are the grade of prostate cancer (Gleason grading system) and the stage of cancer based on physical examination and imaging studies. D'Amico criteria for each risk category are:

- Low risk: PSA < 10, Gleason score ≤ 6, AND clinical stage ≤ T2a

- Intermediate risk: PSA 10-20, Gleason score 7, OR clinical stage T2b/c

- High risk: PSA > 20, Gleason score ≥ 8, OR clinical stage ≥ T3

Given the relative simplicity of the 1998 D'Amico criteria (above), other predictive models of risk stratification based on mathematical probability constructs exist or have been proposed to allow for better matching of treatment decisions with disease features. Studies are being conducted into the incorporation of multiparametric MRI imaging results into nomograms that rely on PSA, Gleason grade, and tumor stage.

Post-treatment monitoring

PSA levels are monitored periodically (e.g., every 6–36 months) after treatment for prostate cancer – more frequently in patients with high-risk disease, less frequently in patients with lower-risk disease. If surgical therapy (i.e., radical prostatectomy) is successful at removing all prostate tissue (and prostate cancer), PSA becomes undetectable within a few weeks. A subsequent rise in PSA level above 0.2 ng/mL L is generally regarded as evidence of recurrent prostate cancer after a radical prostatectomy; less commonly, it may simply indicate residual benign prostate tissue.

Following radiation therapy of any type for prostate cancer, some PSA levels might be detected, even when the treatment ultimately proves to be successful. This makes interpreting the relationship between PSA levels and recurrence/persistence of prostate cancer after radiation therapy more difficult. PSA levels may continue to decrease for several years after radiation therapy. The lowest level is referred to as the PSA nadir. A subsequent increase in PSA levels by 2.0 ng/mL above the nadir is the currently accepted definition of prostate cancer recurrence after radiation therapy.

Recurrent prostate cancer detected by a rise in PSA levels after curative treatment is referred to as a "biochemical recurrence". The likelihood of developing recurrent prostate cancer after curative treatment is related to the pre-operative variables described in the preceding section (PSA level and grade/stage of cancer). Low-risk cancers are the least likely to recur, but they are also the least likely to have required treatment in the first place.

Prostatitis

PSA levels increase in the setting of prostate infection/inflammation (prostatitis), often markedly (> 100).

Forensic identification of semen

PSA was first identified by researchers attempting to find a substance in seminal fluid that would aid in the investigation of rape cases. PSA is now used to indicate the presence of semen in forensic serology. The semen of adult males has PSA levels far in excess of those found in other tissues; therefore, a high level of PSA found in a sample is an indicator that semen may be present. Because PSA is a biomarker that is expressed independently of spermatozoa, it remains useful in identifying semen from vasectomized and azoospermic males.

PSA can also be found at low levels in other body fluids, such as urine and breast milk, thus setting a high minimum threshold of interpretation to rule out false positive results and conclusively state that semen is present. While traditional tests such as crossover electrophoresis have a sufficiently low sensitivity to detect only seminal PSA, newer diagnostics tests developed from clinical prostate cancer screening methods have lowered the threshold of detection down to 4 ng/mL. This level of antigen has been shown to be present in the peripheral blood of males with prostate cancer, and rarely in female urine samples and breast milk.

No studies have been performed to assess the PSA levels in the tissues and secretions of pre-pubescent children. Therefore, the presence of PSA from a high sensitivity (4 ng/mL) test cannot conclusively identify the presence of semen, so care must be taken with the interpretation of such results.

Sources

PSA is produced in the epithelial cells of the prostate, and can be demonstrated in biopsy samples or other histological specimens using immunohistochemistry. Disruption of this epithelium, for example in inflammation or benign prostatic hyperplasia, may lead to some diffusion of the antigen into the tissue around the epithelium, and is the cause of elevated blood levels of PSA in these conditions.

More significantly, PSA remains present in prostate cells after they become malignant. Prostate cancer cells generally have variable or weak staining for PSA, due to the disruption of their normal functioning. Thus, individual prostate cancer cells produce less PSA than healthy cells; the raised serum levels in prostate cancer patients is due to the greatly increased number of such cells, not their individual activity. In most cases of prostate cancer, though, the cells remain positive for the antigen, which can then be used to identify metastasis. Since some high-grade prostate cancers may be entirely negative for PSA, however, histological analysis to identify such cases usually uses PSA in combination with other antibodies, such as prostatic acid phosphatase and CD57.

Mechanism of action

The physiological function of KLK3 is the dissolution of the coagulum, the sperm-entrapping gel composed of semenogelins and fibronectin. Its proteolytic action is effective in liquefying the coagulum so that the sperm can be liberated. The activity of PSA is well regulated. In the prostate, it is present as an inactive pro-form, which is activated through the action of KLK2, another kallikrein-related peptidase. In the prostate, zinc ion concentrations are 10 times higher than in other bodily fluids. Zinc ions have a strong inhibitory effect on the activity of PSA and on that of KLK2, so that PSA is totally inactive.

Further regulation is achieved through pH variations. Although its activity is increased by higher pH, the inhibitory effect of zinc also increases. The pH of semen is slightly alkaline and the concentrations of zinc are high. On ejaculation, semen is exposed to the acidic pH of the vagina, due to the presence of lactic acid. In fertile couples, the final vaginal pH after coitus approaches the 6-7 levels, which coincides well with reduced zinc inhibition of PSA. At these pH levels, the reduced PSA activity is countered by a decrease in zinc inhibition. Thus, the coagulum is slowly liquefied, releasing the sperm in a well-regulated manner.

Biochemistry

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA, also known as kallikrein III, seminin, semenogelase, γ-seminoprotein and P-30 antigen) is a 34-kD glycoprotein produced almost exclusively by the prostate gland. It is a serine protease (EC 3.4.21.77) enzyme, the gene of which is located on the 19th chromosome (19q13) in humans.

History

The discovery of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is beset with controversy; as PSA is present in prostatic tissue and semen, it was independently discovered and given different names, thus adding to the controversy.

Flocks was the first to experiment with antigens in the prostate and 10 years later Ablin reported the presence of precipitation antigens in the prostate.

In 1971, Mitsuwo Hara characterized a unique protein in the semen fluid, gamma-seminoprotein. Li and Beling, in 1973, isolated a protein, E1, from human semen in an attempt to find a novel method to achieve fertility control.

In 1978, Sensabaugh identified semen-specific protein p30, but proved that it was similar to E1 protein, and that prostate was the source. In 1979, Wang purified a tissue-specific antigen from the prostate ('prostate antigen').

PSA was first measured quantitatively in the blood by Papsidero in 1980, and Stamey carried out the initial work on the clinical use of PSA as a marker of prostate cancer.

Serum levels

PSA is normally present in the blood at very low levels. The reference range of less than 4 ng/mL for the first commercial PSA test, the Hybritech Tandem-R PSA test released in February 1986, was based on a study that found 99% of 472 apparently healthy men had a total PSA level below 4 ng/mL.

Increased levels of PSA may suggest the presence of prostate cancer. However, prostate cancer can also be present in the complete absence of an elevated PSA level, in which case the test result would be a false negative.

Obesity has been reported to reduce serum PSA levels. Delayed early detection may partially explain worse outcomes in obese men with early prostate cancer. After treatment, higher BMI also correlates to higher risk of recurrence.

PSA levels can be also increased by prostatitis, irritation, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and recent ejaculation, producing a false positive result. Digital rectal examination (DRE) has been shown in several studies to produce an increase in PSA. However, the effect is clinically insignificant, since DRE causes the most substantial increases in patients with PSA levels already elevated over 4.0 ng/mL.

The "normal" reference ranges for prostate-specific antigen increase with age, as do the usual ranges in cancer, as per table below.

| Age | 40 - 49 | 50 - 59 | 60 - 69 | 70-79 | years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | No cancer | Cancer | No cancer | Cancer | No cancer | Cancer | No cancer | ||

| 5th percentile | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 0.4 | ng/mL or µg/L |

| 95th percentile Non-African-American |

163.0 | 1.2 - 2.9 | 372.5 | 2.07 - 4.7 | 253.2 | 2.8 - 7.2 | 613.2 | 4.0 - 9.0 | |

| 95th percentile African-American |

2.4 - 2.7 | 4.4 - 6.5 | 6.7 - 11 | 7.7 - 13 | |||||

PSA velocity

Despite earlier findings, recent research suggests that the rate of increase of PSA (e.g. >0.35 ng/mL/yr, the 'PSA velocity') is not a more specific marker for prostate cancer than the serum level of PSA.

However, the PSA rate of rise may have value in prostate cancer prognosis. Men with prostate cancer whose PSA level increased by more than 2.0 ng per milliliter during the year before the diagnosis of prostate cancer have a higher risk of death from prostate cancer despite undergoing radical prostatectomy. PSA velocity (PSAV) was found in a 2008 study to be more useful than the PSA doubling time (PSA DT) to help identify those men with life-threatening disease before start of treatment.

Men who are known to be at risk for prostate cancer, and who decide to plot their PSA values as a function of time (i.e., years), may choose to use a semi-log plot. An exponential growth in PSA values appears as a straight line on a semi-log plot, so that a new PSA value significantly above the straight line signals a switch to a new and significantly higher growth rate, i.e., a higher PSA velocity.

Free PSA

Most PSA in the blood is bound to serum proteins. A small amount is not protein-bound and is called 'free PSA'. In men with prostate cancer, the ratio of free (unbound) PSA to total PSA is decreased. The risk of cancer increases if the free to total ratio is less than 25%. (See graph at right.) The lower the ratio is, the greater the probability of prostate cancer. Measuring the ratio of free to total PSA appears to be particularly promising for eliminating unnecessary biopsies in men with PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng/mL. However, both total and free PSA increase immediately after ejaculation, returning slowly to baseline levels within 24 hours.

Inactive PSA

The PSA test in 1994 failed to differentiate between prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and the commercial assay kits for PSA did not provide correct PSA values. Thus with the introduction of the ratio of free-to-total PSA, the reliability of the test has improved. Measuring the activity of the enzyme could add to the ratio of free-to-total PSA and further improve the diagnostic value of test. Proteolytically active PSA has been shown to have an anti-angiogenic effect and certain inactive subforms may be associated with prostate cancer, as shown by MAb 5D3D11, an antibody able to detect forms abundantly represented in sera from cancer patients. The presence of inactive proenzyme forms of PSA is another potential indicator of disease.

Complexed PSA

PSA exists in serum in the free (unbound) form and in a complex with alpha 1-antichymotrypsin; research has been conducted to see if measurements of complexed PSA are more specific and sensitive biomarkers for prostate cancer than other approaches.

PSA in other biologic fluids and tissues

| Fluid | PSA (ng/mL) |

|---|---|

| semen |

200,000 - 5.5 million

|

| amniotic fluid |

0.60 - 8.98

|

| breast milk |

0.47 - 100

|

| saliva |

0

|

| female urine |

0.12 - 3.72

|

| female serum |

0.01 - 0.53

|

It is now clear that the term prostate-specific antigen is a misnomer: it is an antigen but is not specific to the prostate. Although present in large amounts in prostatic tissue and semen, it has been detected in other body fluids and tissues.

In women, PSA is found in female ejaculate at concentrations roughly equal to that found in male semen. Other than semen and female ejaculate, the greatest concentrations of PSA in biological fluids are detected in breast milk and amniotic fluid. Low concentrations of PSA have been identified in the urethral glands, endometrium, normal breast tissue and salivary gland tissue. PSA also is found in the serum of women with breast, lung, or uterine cancer and in some patients with renal cancer.

Tissue samples can be stained for the presence of PSA in order to determine the origin of malignant cells that have metastasized.

Interactions

Prostate-specific antigen has been shown to interact with protein C inhibitor. Prostate-specific antigen interacts with and activates the vascular endothelial growth factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D, which are involved in tumor angiogenesis and in the lymphatic metastasis of tumors.

See also

Further reading

- De Angelis G, Rittenhouse HG, Mikolajczyk SD, Blair Shamel L, Semjonow A (2007). "Twenty Years of PSA: From Prostate Antigen to Tumor Marker". Reviews in Urology. 9 (3): 113–123. PMC 2002501. PMID 17934568.

- Henttu P, Vihko P (June 1994). "Prostate-specific antigen and human glandular kallikrein: two kallikreins of the human prostate". Annals of Medicine. 26 (3): 157–164. doi:10.3109/07853899409147884. PMID 7521173.

- Diamandis EP, Yousef GM, Luo LY, Magklara A, Obiezu CV (March 2000). "The new human kallikrein gene family: implications in carcinogenesis". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 11 (2): 54–60. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(99)00225-8. PMID 10675891. S2CID 25806934.

- Lilja H (November 2003). "Biology of prostate-specific antigen". Urology. 62 (5 Suppl 1): 27–33. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00775-1. PMID 14607215.

External links

- "The Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test: Questions and Answers". National Cancer Institute. 21 March 2022.

- Prostate-Specific+Antigen at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P07288 (Prostate-specific antigen) at the PDBe-KB.

| Blood |

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine |

|

||||||||||||

| Nervous system |

|

||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular/ respiratory |

|

||||||||||||

| Digestive |

|

||||||||||||

| Reproductive/ urinary/ breast |

|

||||||||||||

| General histology |

|

||||||||||||

| Musculoskeletal |

|

||||||||||||

| Activity | |

|---|---|

| Regulation | |

| Classification | |

| Kinetics | |

| Types |

|