Slow-wave sleep

Slow-wave sleep (SWS), often referred to as deep sleep, consists of stage three of non-rapid eye movement sleep. It usually lasts between 70 and 90 minutes and takes place during the first hours of the night. Initially, SWS consisted of both Stage 3, which has 20–50 percent delta wave activity, and Stage 4, which has more than 50 percent delta wave activity.

Overview

This period of sleep is called slow-wave sleep because the EEG activity is synchronized, characterised by slow waves with a frequency range of 0.5–4.5 Hz, relatively high amplitude power with peak-to-peak amplitude greater than 75µV. The first section of the wave signifies a "down state", an inhibition or hyperpolarizing phase in which the neurons in the neocortex are silent. This is the period when the neocortical neurons are able to rest. The second section of the wave signifies an "up state", an excitation or depolarizing phase in which the neurons fire briefly at a high rate. The principal characteristics during slow-wave sleep that contrast with REM sleep are moderate muscle tone, slow or absent eye movement, and lack of genital activity.

Slow-wave sleep is considered important for memory consolidation. This is sometimes referred to as "sleep-dependent memory processing". Impaired memory consolidation has been seen in individuals with primary insomnia, who thus do not perform as well as those who are healthy in memory tasks following a period of sleep. Furthermore, slow-wave sleep improves declarative memory (which includes semantic and episodic memory). A central model has been hypothesized that the long-term memory storage is facilitated by an interaction between the hippocampal and neocortical networks. In several studies, after the subjects have had training to learn a declarative memory task, the density of human sleep spindles present was significantly higher than the signals observed during the control tasks, which involved similar visual stimulation and cognitively-demanding tasks but did not require learning. This associated with the spontaneously occurring wave oscillations that account for the intracellular recordings from thalamic and cortical neurons.

Specifically, SWS presents a role in spatial declarative memory. Reactivation of the hippocampus during SWS is detected after the spatial learning task. In addition, a correlation can be observed between the amplitude of hippocampal activity during SWS and the improvement in spatial memory performance, such as route retrieval, on the following day.

A memory reactivation experiment during SWS was conducted using odor as a cue, given that it does not disturb ongoing sleep, over a prior learning task and sleep sessions. The region of the hippocampus was activated in response to odor re-exposure during SWS. This stage of sleep has an exclusive role as a context cue that reactivates the memories and favors their consolidation. A further study demonstrated that when subjects heard sounds associated with previously shown pictures-locations, the reactivation of individual memory representations was significantly higher during SWS (compared to other sleep stages).

Affective representations are generally better remembered during sleep compared to neutral ones. Emotions with negative salience presented as a cue during SWS show better reactivation, and therefore an enhanced consolidation in comparison to neutral memories. The former was predicted by sleep spindles over SWS, which discriminates the memory processes during sleep as well as facilitating emotional memory consolidation.

Acetylcholine plays an essential role in hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. An increased level of cholinergic activity during SWS is known to be disruptive for memory processing. Considering that acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that modulates the direction of information flow between the hippocampus and neocortex during sleep, its suppression is necessary during SWS in order to consolidate sleep-related declarative memory.

Sleep deprivation studies with humans suggest that the primary function of slow-wave sleep may be to allow the brain to recover from its daily activities. Glucose metabolism in the brain increases as a result of tasks that demand mental activity. Another function affected by slow-wave sleep is the secretion of growth hormone, which is always greatest during this stage. It is also thought to be responsible for a decrease in sympathetic and increase in parasympathetic neural activity.

Prior to 2007, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) divided slow-wave sleep into stages 3 and 4. The two stages are now combined as "Stage three" or N3. An epoch (30 seconds of sleep) which consists of 20% or more slow-wave (delta) sleep is now considered to be stage three.

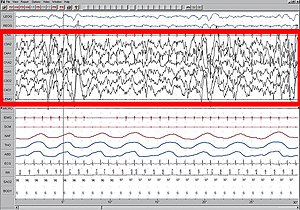

Electroencephalographic characteristics

Large 75-microvolt (0.5–2.0 Hz) delta waves predominate the electroencephalogram (EEG). Stage N3 is defined by the presence of 20% delta waves in any given 30-second epoch of the EEG during sleep, by the current 2007 AASM guidelines.

Longer periods of SWS occur in the first part of the night, primarily in the first two sleep cycles (roughly three hours). Children and young adults will have more total SWS in a night than older adults. The elderly may not go into SWS at all during many nights of sleep.

Slow-wave sleep is an active phenomenon probably brought about by the activation of serotonergic neurons of the raphe system.

The slow-wave seen in the cortical EEG is generated through thalamocortical communication through the thalamocortical (TC) neurons. In the TC neurons, this is generated by the "slow oscillation" and is dependent on membrane potential bistability, a property of these neurons due to an electrophysiological component known as "I t window". "I t window" is due to the overlap underneath activation and inactivation curves if plotted for T-type calcium channels (inward current). If these two curves are multiplied, and another line superimposed on the graph to show a small Ik leak current (outward), then the interplay between these inward (I t window) and outward (small Ik leak), three equilibrium points are seen at −90, −70 and −60 mv, −90 and −60 being stable and −70 unstable. This property allows the generation of slow waves due to an oscillation between two stable points. It is important to note that in in vitro, mGluR must be activated on these neurons to allow a small Ik leak, as seen in in vivo situations.

Functions

Hemispheric asymmetries in the human sleep

Slow-wave sleep is necessary for survival. Some animals, such as dolphins and birds, have the ability to sleep with only one hemisphere of the brain, leaving the other hemisphere awake to carry out normal functions and to remain alert. This kind of sleep is called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep, and is also partially observable in human beings. Indeed, a study reported a unilateral activation of the somatosensorial cortex when a vibrating stimulus was put on the hand of human subjects. The recordings show an important inter-hemispheric change during the first hour of non-REM sleep and consequently the presence of a local and use-dependent aspect of sleep. Another experiment detected a greater number of delta waves in the frontal and central regions of the right hemisphere.

Considering that SWS is the only sleep stage that reports human deep sleep as well as being used in studies with mammals and birds, it is also adopted in experiments revealing the role of hemispheric asymmetries during sleep. A predominance of the left hemisphere in the neural activity can be observed in the default-mode network during SWS. This asymmetry is correlated with the sleep onset latency, which is a sensitive parameter of the so-called first night effect—the reduced quality of sleep during the first session in the laboratory.

The left hemisphere is shown to be more sensitive to deviant stimuli during the first night—compared to the following nights of an experiment. This asymmetry explains further the reduced sleep of half the brain during SWS. Indeed, in comparison to the right one, the left hemisphere plays a vigilant role during SWS.

Furthermore, a faster behavioral reactivity is detected in the left hemisphere during SWS of the first night. The rapid awakening is correlated to the regional asymmetry in the activities of SWS. These findings show that the hemispheric asymmetry in SWS plays a role as a protective mechanism. SWS is therefore sensitive to danger and non-familiar environment, creating a need for vigilance and reactivity during sleep.

Neural control of slow-wave sleep

Several neurotransmitters are involved in sleep and waking patterns: acetylcholine, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, and orexin. Neocortical neurons fire spontaneously during slow-wave sleep, thus they seem to play a role during this period of sleep. Also, these neurons appear to have some sort of internal dialogue, which accounts for the mental activity during this state where there is no information from external signals (because of the synaptic inhibition at the thalamic level). The rate of recall of dreams during this state of sleep is relatively high compared to the other levels of the sleep cycle. This indicates that mental activity is closer to real life events.

Physical healing and growth

Slow-wave sleep is the constructive phase of sleep for recuperation of the mind-body system in which it rebuilds itself after each day. Substances that have been ingested into the body while an organism is awake are synthesized into complex proteins of living tissue. Growth hormone is also secreted during this stage, which leads some scientists to hypothesize that a function of slow wave sleep is to facilitate the healing of muscles as well as repair damage to tissues. Lastly, glial cells within the brain are restored with sugars to provide energy for the brain.

Learning and synaptic homeostasis

Learning and memory formation occurs during wakefulness by the process of long-term potentiation; SWS is associated with the regulation of synapses thus potentiated. SWS has been found to be involved in the downscaling of synapses, in which strongly stimulated or potentiated synapses are kept while weakly potentiated synapses either diminish or are removed. This may be helpful for recalibrating synapses for the next potentiation during wakefulness and for maintaining synaptic plasticity. Notably, new evidence is showing that reactivation and rescaling may be co-occurring during sleep.

Problems associated with slow-wave sleep

Bedwetting, night terrors, and sleepwalking are all common behaviors that can occur during stage three of sleep. These occur most frequently amongst children, who then generally outgrow them. Another problem that may arise is sleep-related eating disorder. An individual will sleep-walk leaving his or her bed in the middle of the night seeking out food, and will eat not having any memory of the event in the morning. Over half of individuals with this disorder become overweight. Sleep-related eating disorder can usually be treated with dopaminergic agonists, or topiramate, which is an anti-seizure medication. This nocturnal eating throughout a family suggests that heredity may be a potential cause of this disorder.

Effects of sleep deprivation

J. A. Horne (1978) reviewed several experiments with humans and concluded that sleep deprivation has no effects on people's physiological stress response or ability to perform physical exercise. It did, however, have an effect on cognitive functions. Some people reported distorted perceptions or hallucinations and lack of concentration on mental tasks. Thus, the major role of sleep does not appear to be rest for the body, but rest for the brain.

When sleep-deprived humans sleep normally again, the recovery percentage for each stage of sleep is not the same. Only seven percent of stages one and two are regained, but 68 percent of stage-four slow-wave sleep and 53 percent of REM sleep are regained. This suggests that stage-four sleep (known today as the deepest part of stage-three sleep) is more important than the other stages.

During slow-wave sleep, there is a significant decline in cerebral metabolic rate and cerebral blood flow. The activity falls to about 75 percent of the normal wakefulness level. The regions of the brain that are most active when awake have the highest level of delta waves during slow-wave sleep. This indicates that rest is geographical. The "shutting down" of the brain accounts for the grogginess and confusion if someone is awakened during deep sleep, since it takes the cerebral cortex time to resume its normal functions.

According to J. Siegel (2005), sleep deprivation results in the build-up of free radicals and superoxides in the brain. Free radicals are oxidizing agents that have one unpaired electron, making them highly reactive. These free radicals interact with electrons of biomolecules and damage cells. In slow-wave sleep, the decreased rate of metabolism reduces the creation of oxygen byproducts, thereby allowing the existing radical species to clear. This is a means of preventing damage to the brain.

Amyloid beta pathology

The accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) in the prefrontal cortex is associated with the disruption or reduction of slow waves of NREM sleep. Therefore, this may reduce the ability for memory consolidation in older adults.

Individual differences

Though SWS is fairly consistent within the individual, it can vary across individuals. Age and gender have been noted as two of the biggest factors that affect this period of sleep. Aging is inversely proportional to the amount of SWS beginning by midlife, so SWS declines with age. Sex differences have also been found, such that females tend to have higher levels of SWS compared to males, at least up until menopause. There have also been studies that have shown differences between races. The results showed that there was a lower percentage of SWS in African Americans compared to Caucasians, but since there are many influencing factors (e.g., body mass index, sleep-disordered breathing, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension), this potential difference must be investigated further.

Mental disorders play a role in individual differences in the quality and quantity of SWS: subjects with depression show a lower amplitude of slow-wave activity (SWA) compared to healthy participants. Sex differences also persist in the former group: depressed men present significantly lower SWA amplitude. This sex divergence is twice as large as the one observed in healthy subjects. However, no age-related difference concerning SWS can be observed in the depressed group.

Brain regions

Some of the brain regions implicated in the induction of slow-wave sleep include:

- the parafacial zone (GABAergic neurons), located within the medulla oblongata

- the nucleus accumbens core (GABAergic medium spiny neurons; specifically, the subset of these neurons that expresses both D2-type dopamine receptors and adenosine A2A receptors), located within the striatum

- the ventrolateral preoptic area (GABAergic neurons), located within the hypothalamus

- the lateral hypothalamus (melanin-concentrating hormone-releasing neurons), located within the hypothalamus

Drugs

The chemical gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) has been studied to increase SWS. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permits the use of GHB under the trade name Xyrem to reduce cataplexy attacks and excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy.

See also

Further reading

- Massimini M, Ferrarelli F, Huber R, Esser SK, Singh H, Tononi G (September 2005). "Breakdown of cortical effective connectivity during sleep". Science. 309 (5744): 2228–32. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2228M. doi:10.1126/science.1117256. PMID 16195466. S2CID 38498750.

- Cicogna P, Natale V, Occhionero M, Bosinelli M (2000). "Slow wave and REM sleep mentation". Sleep Research Online. 3 (2): 67–72. PMID 11382903.

- Vogel G, Foulkes D, Trosman H (March 1966). "Ego functions and dreaming during sleep onset". Archives of General Psychiatry. 14 (3): 238–48. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1966.01730090014003. PMID 5903415.

- Rock A (2004). The Mind at Night.

- Warren, Jeff (2007). "The Slow Wave". The Head Trip: Adventures on the Wheel of Consciousness. ISBN 978-0-679-31408-0.

|

Sleep and sleep disorders

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages of sleep cycles | |||||||||||||||

| Brain waves | |||||||||||||||

| Sleep disorders |

|

||||||||||||||

| Daily life | |||||||||||||||