Temporal lobe epilepsy

| Temporal lobe epilepsy | |

|---|---|

| |

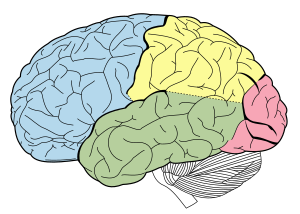

| Lobes of the brain. Temporal lobe in green | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a chronic disorder of the nervous system which is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked focal seizures that originate in the temporal lobe of the brain and last about one or two minutes. TLE is the most common form of epilepsy with focal seizures. A focal seizure in the temporal lobe may spread to other areas in the brain when it may become a focal to bilateral seizure.

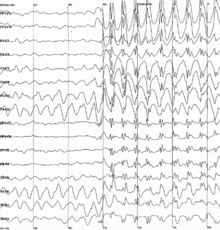

TLE is diagnosed by conducting a medical history, physical exam, blood tests, electroencephalogram and brain imaging. It can have a number of causes such as head injury, stroke, brain infections, structural lesions in the brain, brain tumors, or it can be of unknown cause. Treatment begins with anticonvulsant medication. Surgery may be an option, especially when there is an observable abnormality in the brain. A treatment option is electrical stimulation of the vagal nerve through a surgically implanted device called the vagus nerve stimulator (VNS).

Types

There are 4 categories of epilepsy defined by seizure onset: focal onset, generalized onset, combined generalized and focal onset and unknown onset.Focal seizures account for approximately sixty percent of all adult cases. Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the single most common form of focal seizure.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) describes two main types of temporal lobe epilepsy: mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE), arising in the hippocampus, the parahippocampal gyrus and the amygdala which are located in the inner (medial) aspect of the temporal lobe, and lateral temporal lobe epilepsy (LTLE), the rarer type, arising in the neocortex at the outer (lateral) surface of the temporal lobe.

Signs and symptoms

When a seizure begins in the temporal lobe, its effects depend on the precise location of its point of origin, its locus. In 1981, the ILAE recognized three types of seizures occurring in temporal lobe epilepsy. The classification was based on EEG findings. However, as of 2017 the general classification of seizures has been revised. The newer classification uses three key features: where the seizures begin, the level of awareness during a seizure, and other features.

Focal seizures

Focal seizures in the temporal lobe involve small areas of the lobe such as the amygdala and hippocampus.

The ILAE 2017 seizure classification distinguishes focal onset seizures, as focal aware and focal impaired awareness seizures.

Focal aware seizures

Focal aware means that the level of awareness is not altered during the seizure. In temporal lobe epilepsy, a focal seizure usually causes abnormal sensations only. Often, the patient cannot describe the sensations.

These may be:

- Sensations such as déjà vu (a feeling of familiarity), jamais vu (a feeling of unfamiliarity)

- Amnesia of a single memory or set of memories

- A sudden sense of unprovoked fear and anxiety

- Nausea

- Ictal vomiting

- Auditory, visual, olfactory, gustatory, or tactile hallucinations; olfactory hallucinations often seem indescribable to patients beyond "pleasant" or "unpleasant"

- The psychotic symptoms in epilepsy share some qualities with schizophrenic psychosis, such as positive symptoms of paranoid delusions and hallucinations. Psychotic syndromes in epilepsy are most common but not exclusively associated with temporal lobe epilepsy.

- Visual distortions such as macropsia and micropsia

- Dissociation or derealisation

- Synesthesia (stimulation of one sense experienced in a second sense)

- Dysphoric or euphoric feelings, fear, anger, and other emotions

Focal aware seizures are often called "auras" when they serve as a warning sign of a subsequent seizure. Regardless, an aura is actually a seizure itself, and such a focal seizure may or may not progress to a focal impaired awareness seizure. People who experience only focal aware seizures may not recognize what they are, nor seek medical care.

Focal impaired awareness seizures

Focal impaired awareness seizures are seizures which impair consciousness to some extent: they alter the person's ability to interact normally with their environment. They usually begin with a focal aware seizure, then spread to a larger portion of the temporal lobe, resulting in impaired consciousness. They may include autonomic and psychic features present in focal aware seizures.

Signs may include:

- Motionless staring

- Automatic movements of the hands or mouth

- Confusion and disorientation

- Altered ability to respond to others, unusual speech

- Transient aphasia (losing ability to speak, read, or comprehend spoken word)

These seizures tend to have a warning or aura before they occur, and when they occur they generally tend to last only 1–2 minutes. It is not uncommon for an individual to be tired or confused for up to 15 minutes after a seizure has occurred, although postictal confusion can last for hours or even days. Though they may not seem harmful, due to the fact that the individual does not normally seize, they can be extremely harmful if the individual is left alone around dangerous objects or in situations requiring acute awareness, such as steering a vehicle or operating machinery. With this type, some people do not even realize they are having a seizure and most of the time their memory from right before to after the seizure is lost.

Focal to bilateral seizures or generalized seizures

Seizures which begin in the temporal lobe, and then spread to involve both sides of the brain are termed focal to bilateral. Where both sides of the brain or the whole brain are involved from the onset, these seizures are known as generalized seizures and may be tonic clonic. The arms, trunk, and legs stiffen (the tonic phase), in either a flexed or extended position, and then jerk (the clonic phase). These were previously known as grand mal seizures. The word grand mal comes from the French term, meaning major affliction.

Postictal period

There is some period of recovery in which neurological function is altered after each of these seizure types. This is the postictal state. The degree and length of postictal impairment directly correlates with the severity of the seizure type. Focal aware seizures often last less than sixty seconds; focal with impaired awareness seizures may last up to two minutes; and generalized tonic clonic seizures may last up to three minutes. The postictal state in seizures other than focal aware may last much longer than the seizure itself.

Because a major function of the temporal lobe is short-term memory, a focal with impaired awareness seizure, and a focal to bilateral seizure can cause amnesia for the period of the seizure, meaning that the seizure may not be remembered.

Complications

Depression

Individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy have a higher prevalence of depression than the general population. Although the psychosocial impacts of epilepsy may be causative, there are also links in the phenomenology and neurobiology of TLE and depression.

Memory

The temporal lobe and particularly the hippocampus play an important role in memory processing. Declarative memory (memories which can be consciously recalled) is formed in the area of the hippocampus called the dentate gyrus.

Temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with memory disorders and loss of memory. Animal models and clinical studies show that memory loss correlates with temporal lobe neuronal loss in temporal lobe epilepsy. Verbal memory deficit correlates with pyramidal cell loss in TLE. This is more so on the left in verbal memory loss. Neuronal loss on the right is more prominent in non-verbal (visuospatial memory loss).

Childhood onset

After childhood onset, one third will "grow out" of TLE, finding a lasting remission up to an average of 20 years. The finding of a lesion such as hippocampal sclerosis (a scar in the hippocampus), tumour, or dysplasia, on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) predicts the intractability of seizures.

Personality

The effect of temporal lobe epilepsy on personality is a historical observation dating to the 1800s. Personality and behavioural change in temporal lobe epilepsy is seen as a chronic condition when it persists for more than three months.

Geschwind syndrome is a set of behavioural phenomena seen in some people with TLE. Documented by Norman Geschwind, signs include: hypergraphia (compulsion to write (or draw) excessively), hyperreligiosity (intense religious or philosophical experiences or interests), hyposexuality (reduced sexual interest or drive), circumstantiality (result of a non-linear thought pattern, talks at length about irrelevant and trivial details). The personality changes generally vary by hemisphere.

The existence of a "temporal lobe epileptic personality" and of Geschwind syndrome have been disputed and research is inconclusive.

Causes

The causes of TLE include mesial temporal sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, brain infections, such as encephalitis and meningitis, hypoxic brain injury, stroke, cerebral tumours, and genetic syndromes. Temporal lobe epilepsy is not the result of psychiatric illness or fragility of the personality.

Febrile seizures

Although the theory is controversial, there is a link between febrile seizures (seizures coinciding with episodes of fever in young children) and subsequent temporal lobe epilepsy, at least epidemiologically.

Human herpes virus 6

In the mid-1980s, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was suggested as a possible causal link between febrile convulsions and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. However, although the virus is found in temporal lobe tissue at surgery for TLE, it has not been recognised as a major factor in febrile seizures or TLE.

Reelin

Dispersion of the granule cell layer in the hippocampal dentate gyrus is occasionally seen in temporal lobe epilepsy and has been linked to the downregulation of reelin, a protein that normally keeps the layer compact by containing neuronal migration. It is unknown whether changes in reelin expression play a role in epilepsy.

Pathophysiology

Neuronal loss

In TLE, there is loss of neurons in region CA1 and CA3 of the hippocampus. There is also damage to mossy cells and inhibitory interneurons in the hilar region of the hippocampus (region IV) and to the granule cells of the dentate gyrus. In animal models, neuronal loss occurs during seizures but in humans, neuronal loss predates the first seizure and does not necessarily continue with seizure activity. The loss of the GABA-mediated inhibitory interneurons may increase the hyperexcitability of neurons of the hippocampus leading to recurrent seizures. According to the "dormant basket cell" hypothesis, mossy cells normally excite basket cells which in turn, inhibit granule cells. Loss of mossy cells lowers the threshold of action potentials of the granule cells.

GABA reversal

In certain patients with temporal lobe epilepsy it has been found that the subiculum could generate epileptic activity. It has been found that GABA reversal potential is depolarising in the subpopulation of the pyramidal cells due to the lack of KCC2 co-transporter. It has been shown that it is theoretically possible to generate seizures in the neural networks due to down-regulation of KCC2, consistent with the chloride measurements during the transition to seizure and KCC2 blockade experiments.

Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus

Granule cell dispersion is a type of developmental migration and a pathological change found in the TLE brain which was first described in 1990. The granule cells of the dentate gyrus are tightly packed forming a uniform, laminated layer with no monosynaptic connections. This structure provides a filter for the excitability of neurons.

In TLE, granule cells are lost, the structure is no longer closely packed and there are changes in the orientation of dendrites. These changes may or may not be epileptogenic. Recent work on human temporal epilepsy identified electrophysiological, morphological and spine density changes in remaining granule cells in dentate gyrus. It has been found that in the remaining granule cells from dentate gyrus have faster response to the injected current, have larger cell surface area and have about twice as many spines in later sclerosis stages (Wyler Grade 4) compared to the early sclerosis stages (Wyler Grade 1). For instance, if the dendrites of granule cells reconnect, it may be in a way (through the laminar planes) that allows hyperexcitability. However, not all patients have granule cell dispersion.

Aberrant mossy fiber sprouting

Mossy fibers are the axons of granule cells. They project into the hilus of the dentate gyrus and stratum lucidum in the CA3 region giving inputs to both excitatory and inhibitory neurons.

In the TLE brain, where granule cells are damaged or lost, axons, the mossy fibres, 'sprout' in order to reconnect to other granule cell dendrites. This is an example of synaptic reorganization. This was noted in human tissue in 1974 and in animal models in 1985. In TLE, the sprouting mossy fibres are larger than in the normal brain and their connections may be aberrant. Mossy fibre sprouting continues from one week to two months after injury.

Aberrant mossy fibre sprouting may create excitatory feedback circuits that lead to temporal lobe seizures. This is evident in intracellular recordings. Stimulation of aberrant mossy fibre areas increases the excitatory postsynaptic potential response.

However, aberrant mossy fiber sprouting may inhibit excitatory transmission by synapsing with basket cells which are inhibitory neurons and by releasing GABA and neuropeptide Y which are inhibitory neurotransmitters. Also, in animal models, granule cell hyper-excitability is recorded before aberrant mossy fibre sprouting has occurred.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy can include the following methods: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scans, positron emission tomography (PET), EEG, and magnetoencephalography.

Imaging

CT scan is useful as the emergency situations when the suspected cause of epilepsy is due to conditions such as intracerebral haemorrhage, or brain abscesses, or when MRI imaging is not readily available or there is any contraindications to MRI such as the presence of cardiac pacemakers or cochlear implants in the subject's body. CT scan also detect some abnormal calcifications in the brain that is characteristic of diseases such as tuberous sclerosis and Sturge–Weber syndrome. However, CT scan is not sensitive or specific enough when compared in MRI in detecting the common causes of epilepsy such as small tumours, vascular malformations, abnormalities of cerebral cortex development, or abnormalities in the medial part of the temporal lobe.

MRI is the imaging choice when assessing those with epilepsy. In newly diagnosed epilepsy, MRI can detect brain lesion in up to 12 to 14% of the cases. However, for those with chronic epilepsy, MRI can detect brain lesion in 80% of the cases. However, in cases where there is definite clinical and EEG diagnosis of idiopathic generalized epilepsy, or Rolandic epilepsy, MRI scan is not needed.

Differential diagnosis

Other medical conditions with similar symptoms include panic attacks, psychosis spectrum disorders, tardive dyskinesia, and occipital lobe epilepsy.

Treatments

Anticonvulsants

Many anticonvulsant oral medications are available for the management of temporal lobe seizures. Most anticonvulsants function by decreasing the excitation of neurons, for example, by blocking fast or slow sodium channels or by modulating calcium channels; or by enhancing the inhibition of neurons, for example by potentiating the effects of inhibitory neurotransmitters like GABA.

In TLE, the most commonly used older medications are phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, valproate, and phenobarbital. Newer drugs, such as gabapentin, topiramate, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, pregabalin, tiagabine, lacosamide, and zonisamide promise similar effectiveness, with possibly fewer side-effects. Felbamate and vigabatrin are newer, but can have serious adverse effects so they are not considered as first-line treatments.

Up to one third of patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy will not have adequate seizure control with medication alone. For patients with medial TLE whose seizures remain uncontrolled after trials of several types of anticonvulsants (that is, the epilepsy is intractable), surgical excision of the affected temporal lobe may be considered.

Surgical interventions

Epilepsy surgery has been performed since the 1860s and doctors have observed that it is highly effective in producing freedom from seizures. However, it was not until 2001 that a scientifically sound study was carried out to examine the effectiveness of temporal lobectomy.

Temporal lobe surgery can be complicated by decreased cognitive function. However, after temporal lobectomy, memory function is supported by the opposite temporal lobe; and recruitment of the frontal lobe.Cognitive rehabilitation may also help.

Other treatments

Where surgery is not recommended, further management options include new (including experimental) anticonvulsants, and vagus nerve stimulation. The ketogenic diet is also recommended for children, and some adults. Other options include brain cortex responsive neural stimulators, deep brain stimulation, stereotactic radiosurgery, such as the gamma knife, and laser ablation.

Effects on society

The first to record and catalog the abnormal symptoms and signs of TLE was Norman Geschwind. He found a constellation of symptoms that included hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity, collapse, and pedantism, now called Geschwind syndrome.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran explored the neural basis of the hyperreligiosity seen in TLE using the galvanic skin response (GSR), which correlates with emotional arousal, to determine whether the hyperreligiosity seen in TLE was due to an overall heightened emotional state or was specific to religious stimuli. Ramachandran presented two subjects with neutral, sexually arousing and religious words while measuring GSR. Ramachandran was able to show that patients with TLE showed enhanced emotional responses to the religious words, diminished responses to the sexually charged words, and normal responses to the neutral words. This study was presented as an abstract at a neuroscience conference and referenced in Ramachandran's book, Phantoms in the Brain, but it has never been published in the peer-reviewed scientific press.

A study in 2015, reported that intrinsic religiosity and religiosity outside of organized religion were higher in patients with epilepsy than in the control group. Lower education level, abnormal background EEG activity, and hippocampal sclerosis have been found to be contributing factors for religiosity in TLE.

TLE has been suggested as a materialistic explanation for the revelatory experiences of prominent religious figures such as Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Mohammed, Saint Paul, Joan of Arc,Saint Teresa of Ávila, and Joseph Smith. These experiences are described (in possibly unreliable accounts) as complex interactions with their visions; but possibly (and dependent on the reliability of historical accounts, often made by acolytes) lack the stereotypy, amnestic periods, and automatisms or generalized motor events, which are characteristic of TLE. Psychiatric conditions with psychotic spectrum symptoms might be more plausible physical explanation of these experiences. It has been suggested that Pope Pius IX's doctrine of the immaculate conception was influenced by his forensically diagnosed partial epilepsy.

In 2016, a case history found that a male temporal lobe epileptic patient experienced a vision of God following a temporal lobe seizure, while undergoing EEG monitoring. The patient reported that God had sent him to the world to "bring redemption to the people of Israel". The purported link between TLE and religiosity has inspired work by Michael Persinger and other researchers in the field of neurotheology. Others have questioned the evidence for a link between temporal lobe epilepsy and religiosity.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Basics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management |

|

||||||||||

| Personal issues | |||||||||||

| Seizure types |

|

||||||||||

| Related disorders | |||||||||||

| Organizations | |||||||||||

| Authority control: National |

|---|