Adderall

| |

| |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| amphetamine aspartate monohydrate | 25% – stimulant (12.5% levo; 12.5% dextro) |

| amphetamine sulfate | 25% – stimulant (12.5% levo; 12.5% dextro) |

| dextroamphetamine saccharate | 25% – stimulant (0% levo; 25% dextro) |

| dextroamphetamine sulfate | 25% – stimulant (0% levo; 25% dextro) |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Adderall, Adderall XR, Mydayis |

| Other names | Mixed amphetamine salts; MAS |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601234 |

| License data | |

| Dependence liability |

Moderate - high |

| Routes of administration |

By mouth, insufflation, rectal, sublingual |

| Drug class | CNS stimulant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| (verify) | |

Adderall and Mydayis are trade names for a combination drug called mixed amphetamine salts containing four salts of amphetamine. The mixture is composed of equal parts racemic amphetamine and dextroamphetamine, which produces a (3:1) ratio between dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, the two enantiomers of amphetamine. Both enantiomers are stimulants, but differ enough to give Adderall an effects profile distinct from those of racemic amphetamine or dextroamphetamine, which are marketed as Evekeo and Dexedrine/Zenzedi, respectively. Adderall is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. It is also used illicitly as an athletic performance enhancer, cognitive enhancer, appetite suppressant, and recreationally as a euphoriant. It is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the phenethylamine class.

Adderall is generally well-tolerated and effective in treating symptoms of ADHD and narcolepsy. At therapeutic doses, Adderall causes emotional and cognitive effects such as euphoria, change in sex drive, increased wakefulness, and improved cognitive control. At these doses, it induces physical effects such as a faster reaction time, fatigue resistance, and increased muscle strength. In contrast, much larger doses of Adderall can impair cognitive control, cause rapid muscle breakdown, provoke panic attacks, or induce a psychosis (e.g., paranoia, delusions, hallucinations). The side effects of Adderall vary widely among individuals, but most commonly include insomnia, dry mouth, loss of appetite, and weight loss. The risk of developing an addiction or dependence is insignificant when Adderall is used as prescribed at fairly low daily doses, such as those used for treating ADHD; however, the routine use of Adderall in larger daily doses poses a significant risk of addiction or dependence due to the pronounced reinforcing effects that are present at high doses. Recreational doses of amphetamine are generally much larger than prescribed therapeutic doses, and carry a far greater risk of serious adverse effects.

The two amphetamine enantiomers that compose Adderall (levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine) alleviate the symptoms of ADHD and narcolepsy by increasing the activity of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine in the brain, which results in part from their interactions with human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in neurons. Dextroamphetamine is a more potent CNS stimulant than levoamphetamine, but levoamphetamine has slightly stronger cardiovascular and peripheral effects and a longer elimination half-life than dextroamphetamine. The levoamphetamine component of Adderall has been reported to improve the treatment response in some individuals relative to dextroamphetamine alone. Adderall's active ingredient, amphetamine, shares many chemical and pharmacological properties with the human trace amines, particularly phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine, the latter of which is a positional isomer of amphetamine. In 2020, Adderall was the 22nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 26 million prescriptions.

Uses

Medical

Adderall is commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy (a sleep disorder). Long-term amphetamine exposure at sufficiently high doses in some animal species is known to produce abnormal dopamine system development or nerve damage, but in some cases with humans with ADHD, pharmaceutical amphetamines at therapeutic dosages may improve brain development and nerve growth. Reviews of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD, and improves function in several parts of the brain, such as the right caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia.

Reviews of clinical stimulant research have established the safety and effectiveness of long-term continuous amphetamine use for the treatment of ADHD.Randomized controlled trials of continuous stimulant therapy for the treatment of ADHD spanning 2 years have demonstrated treatment effectiveness and safety. Two reviews have indicated that long-term continuous stimulant therapy for ADHD is effective for reducing the core symptoms of ADHD (i.e., hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity), enhancing quality of life and academic achievement, and producing improvements in a large number of functional outcomes across 9 categories of outcomes related to academics, antisocial behavior, driving, non-medicinal drug use, obesity, occupation, self-esteem, service use (i.e., academic, occupational, health, financial, and legal services), and social function. One review highlighted a nine-month randomized controlled trial of amphetamine treatment for ADHD in children that found an average increase of 4.5 IQ points, continued increases in attention, and continued decreases in disruptive behaviors and hyperactivity. Another review indicated that, based upon the longest follow-up studies conducted to date, lifetime stimulant therapy that begins during childhood is continuously effective for controlling ADHD symptoms and reduces the risk of developing a substance use disorder as an adult.

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems; these functional impairments involve impaired dopamine neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic projection and norepinephrine neurotransmission in the noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to the prefrontal cortex. Psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine are effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems. Approximately 80% of those who use these stimulants see improvements in ADHD symptoms. Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members, perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans. The Cochrane reviews on the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults with pharmaceutical amphetamines stated that short-term studies have demonstrated that these drugs decrease the severity of symptoms, but they have higher discontinuation rates than non-stimulant medications due to their adverse side effects. A Cochrane review on the treatment of ADHD in children with tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome indicated that stimulants in general do not make tics worse, but high doses of dextroamphetamine could exacerbate tics in some individuals.

Available forms

Adderall is available as immediate-release (IR) tablets or two different extended-release (XR) formulations. The extended-release capsules are generally used in the morning. A shorter, 12-hour extended-release formulation is available under the brand Adderall XR and is designed to provide a therapeutic effect and plasma concentrations identical to taking two doses four hours apart. The longer extended-release formulation, approved for 16 hours, is available under the brand Mydayis. In the United States, the immediate and extended release formulations of Adderall are both available as generic drugs.

Enhancing performance

Cognitive performance

In 2015, a systematic review and a meta-analysis of high quality clinical trials found that, when used at low (therapeutic) doses, amphetamine produces modest yet unambiguous improvements in cognition, including working memory, long-term episodic memory, inhibitory control, and some aspects of attention, in normal healthy adults; these cognition-enhancing effects of amphetamine are known to be partially mediated through the indirect activation of both dopamine receptor D1 and adrenoceptor α2 in the prefrontal cortex. A systematic review from 2014 found that low doses of amphetamine also improve memory consolidation, in turn leading to improved recall of information. Therapeutic doses of amphetamine also enhance cortical network efficiency, an effect which mediates improvements in working memory in all individuals. Amphetamine and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency (motivation to perform a task) and increase arousal (wakefulness), in turn promoting goal-directed behavior. Stimulants such as amphetamine can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid. Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, 5–35% of college students use diverted ADHD stimulants, which are primarily used for enhancement of academic performance rather than as recreational drugs. However, high amphetamine doses that are above the therapeutic range can interfere with working memory and other aspects of cognitive control.

Physical performance

Amphetamine is used by some athletes for its psychological and athletic performance-enhancing effects, such as increased endurance and alertness; however, non-medical amphetamine use is prohibited at sporting events that are regulated by collegiate, national, and international anti-doping agencies. In healthy people at oral therapeutic doses, amphetamine has been shown to increase muscle strength, acceleration, athletic performance in anaerobic conditions, and endurance (i.e., it delays the onset of fatigue), while improving reaction time. Amphetamine improves endurance and reaction time primarily through reuptake inhibition and release of dopamine in the central nervous system. Amphetamine and other dopaminergic drugs also increase power output at fixed levels of perceived exertion by overriding a "safety switch", allowing the core temperature limit to increase in order to access a reserve capacity that is normally off-limits. At therapeutic doses, the adverse effects of amphetamine do not impede athletic performance; however, at much higher doses, amphetamine can induce effects that severely impair performance, such as rapid muscle breakdown and elevated body temperature.

Adderall has been banned in the National Football League (NFL), Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA). In leagues such as the NFL, there is a very rigorous process required to obtain an exemption to this rule even when the athlete has been medically prescribed the drug by their physician.

Recreational

Adderall has high potential for misuse as a recreational drug. Adderall tablets can either be swallowed, crushed and snorted, or dissolved in water and injected. Injection into the bloodstream can be dangerous because insoluble fillers within the tablets can block small blood vessels.

Many postsecondary students have reported using Adderall for study purposes in different parts of the developed world. Among these students, some of the risk factors for misusing ADHD stimulants recreationally include: possessing deviant personality characteristics (i.e., exhibiting delinquent or deviant behavior), inadequate accommodation of disability, basing one's self-worth on external validation, low self-efficacy, earning poor grades, and having an untreated mental health disorder.

Contraindications

Adverse effects

The adverse side effects of Adderall are many and varied, but the amount of substance consumed is the primary factor in determining the likelihood and severity of side effects. Adderall is currently approved for long-term therapeutic use by the USFDA.Recreational use of Adderall generally involves far larger doses and is therefore significantly more dangerous, involving a much greater risk of serious adverse drug effects than dosages used for therapeutic purposes.

Physical

Cardiovascular side effects can include hypertension or hypotension from a vasovagal response, Raynaud's phenomenon (reduced blood flow to the hands and feet), and tachycardia (increased heart rate). Sexual side effects in males may include erectile dysfunction, frequent erections, or prolonged erections. Gastrointestinal side effects may include abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea. Other potential physical side effects include appetite loss, blurred vision, dry mouth, excessive grinding of the teeth, nosebleed, profuse sweating, rhinitis medicamentosa (drug-induced nasal congestion), reduced seizure threshold, tics (a type of movement disorder), and weight loss. Dangerous physical side effects are rare at typical pharmaceutical doses.

Amphetamine stimulates the medullary respiratory centers, producing faster and deeper breaths. In a normal person at therapeutic doses, this effect is usually not noticeable, but when respiration is already compromised, it may be evident. Amphetamine also induces contraction in the urinary bladder sphincter, the muscle which controls urination, which can result in difficulty urinating. This effect can be useful in treating bed wetting and loss of bladder control. The effects of amphetamine on the gastrointestinal tract are unpredictable. If intestinal activity is high, amphetamine may reduce gastrointestinal motility (the rate at which content moves through the digestive system); however, amphetamine may increase motility when the smooth muscle of the tract is relaxed. Amphetamine also has a slight analgesic effect and can enhance the pain relieving effects of opioids.

USFDA-commissioned studies from 2011 indicate that in children, young adults, and adults there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, heart attack, and stroke) and the medical use of amphetamine or other ADHD stimulants. However, amphetamine pharmaceuticals are contraindicated in individuals with cardiovascular disease.

Psychological

At normal therapeutic doses, the most common psychological side effects of amphetamine include increased alertness, apprehension, concentration, initiative, self-confidence and sociability, mood swings (elated mood followed by mildly depressed mood), insomnia or wakefulness, and decreased sense of fatigue. Less common side effects include anxiety, change in libido, grandiosity, irritability, repetitive or obsessive behaviors, and restlessness; these effects depend on the user's personality and current mental state.Amphetamine psychosis (e.g., delusions and paranoia) can occur in heavy users. Although very rare, this psychosis can also occur at therapeutic doses during long-term therapy. According to the USFDA, "there is no systematic evidence" that stimulants produce aggressive behavior or hostility.

Amphetamine has also been shown to produce a conditioned place preference in humans taking therapeutic doses, meaning that individuals acquire a preference for spending time in places where they have previously used amphetamine.

Reinforcement disorders

Addiction

| Addiction and dependence glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Transcription factor glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

|

|

Addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use, but is unlikely to occur from long-term medical use at therapeutic doses; in fact, lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD that begins during childhood reduces the risk of developing substance use disorders as an adult. Pathological overactivation of the mesolimbic pathway, a dopamine pathway that connects the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, plays a central role in amphetamine addiction. Individuals who frequently self-administer high doses of amphetamine have a high risk of developing an amphetamine addiction, since chronic use at high doses gradually increases the level of accumbal ΔFosB, a "molecular switch" and "master control protein" for addiction. Once nucleus accumbens ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it begins to increase the severity of addictive behavior (i.e., compulsive drug-seeking) with further increases in its expression. While there are currently no effective drugs for treating amphetamine addiction, regularly engaging in sustained aerobic exercise appears to reduce the risk of developing such an addiction. Exercise therapy improves clinical treatment outcomes and may be used as an adjunct therapy with behavioral therapies for addiction.

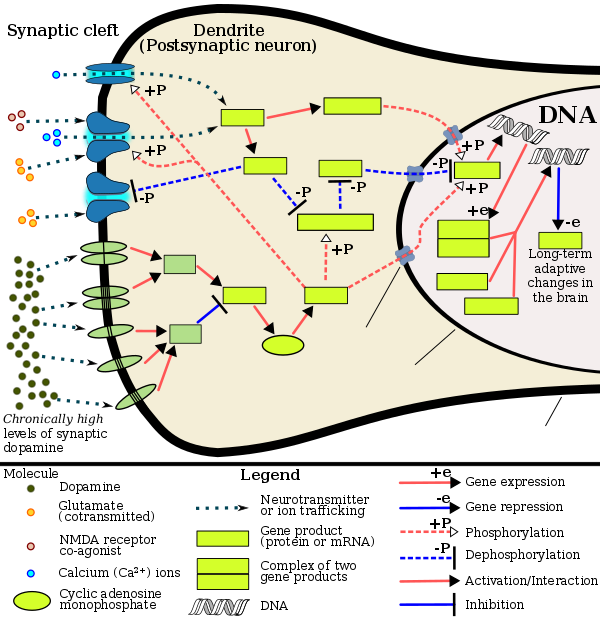

Biomolecular mechanisms

Chronic use of amphetamine at excessive doses causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic projection, which arise through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms. The most important transcription factors that produce these alterations are Delta FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (ΔFosB), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). ΔFosB is the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because ΔFosB overexpression (i.e., an abnormally high level of gene expression which produces a pronounced gene-related phenotype) in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural adaptations and regulates multiple behavioral effects (e.g., reward sensitization and escalating drug self-administration) involved in addiction. Once ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it induces an addictive state that becomes increasingly more severe with further increases in ΔFosB expression. It has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, propofol, and substituted amphetamines, among others.

ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase enzyme, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in its expression. Sufficiently overexpressing ΔJunD in the nucleus accumbens with viral vectors can completely block many of the neural and behavioral alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB). Similarly, accumbal G9a hyperexpression results in markedly increased histone 3 lysine residue 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) and blocks the induction of ΔFosB-mediated neural and behavioral plasticity by chronic drug use, which occurs via H3K9me2-mediated repression of transcription factors for ΔFosB and H3K9me2-mediated repression of various ΔFosB transcriptional targets (e.g., CDK5). ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise. Since both natural rewards and addictive drugs induce the expression of ΔFosB (i.e., they cause the brain to produce more of it), chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological state of addiction. Consequently, ΔFosB is the most significant factor involved in both amphetamine addiction and amphetamine-induced sexual addictions, which are compulsive sexual behaviors that result from excessive sexual activity and amphetamine use. These sexual addictions are associated with a dopamine dysregulation syndrome which occurs in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs.

The effects of amphetamine on gene regulation are both dose- and route-dependent. Most of the research on gene regulation and addiction is based upon animal studies with intravenous amphetamine administration at very high doses. The few studies that have used equivalent (weight-adjusted) human therapeutic doses and oral administration show that these changes, if they occur, are relatively minor. This suggests that medical use of amphetamine does not significantly affect gene regulation.

Pharmacological treatments

As of December 2019, there is no effective pharmacotherapy for amphetamine addiction. Reviews from 2015 and 2016 indicated that TAAR1-selective agonists have significant therapeutic potential as a treatment for psychostimulant addictions; however, as of February 2016, the only compounds which are known to function as TAAR1-selective agonists are experimental drugs. Amphetamine addiction is largely mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors in the nucleus accumbens;magnesium ions inhibit NMDA receptors by blocking the receptor calcium channel. One review suggested that, based upon animal testing, pathological (addiction-inducing) psychostimulant use significantly reduces the level of intracellular magnesium throughout the brain.Supplemental magnesium treatment has been shown to reduce amphetamine self-administration (i.e., doses given to oneself) in humans, but it is not an effective monotherapy for amphetamine addiction.

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2019 assessed the efficacy of 17 different pharmacotherapies used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for amphetamine and methamphetamine addiction; it found only low-strength evidence that methylphenidate might reduce amphetamine or methamphetamine self-administration. There was low- to moderate-strength evidence of no benefit for most of the other medications used in RCTs, which included antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, sertraline), antipsychotics (aripiprazole), anticonvulsants (topiramate, baclofen, gabapentin), naltrexone, varenicline, citicoline, ondansetron, prometa, riluzole, atomoxetine, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil.

Behavioral treatments

A 2018 systematic review and network meta-analysis of 50 trials involving 12 different psychosocial interventions for amphetamine, methamphetamine, or cocaine addiction found that combination therapy with both contingency management and community reinforcement approach had the highest efficacy (i.e., abstinence rate) and acceptability (i.e., lowest dropout rate). Other treatment modalities examined in the analysis included monotherapy with contingency management or community reinforcement approach, cognitive behavioral therapy, 12-step programs, non-contingent reward-based therapies, psychodynamic therapy, and other combination therapies involving these.

Additionally, research on the neurobiological effects of physical exercise suggests that daily aerobic exercise, especially endurance exercise (e.g., marathon running), prevents the development of drug addiction and is an effective adjunct therapy (i.e., a supplemental treatment) for amphetamine addiction. Exercise leads to better treatment outcomes when used as an adjunct treatment, particularly for psychostimulant addictions. In particular, aerobic exercise decreases psychostimulant self-administration, reduces the reinstatement (i.e., relapse) of drug-seeking, and induces increased dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) density in the striatum. This is the opposite of pathological stimulant use, which induces decreased striatal DRD2 density. One review noted that exercise may also prevent the development of a drug addiction by altering ΔFosB or c-Fos immunoreactivity in the striatum or other parts of the reward system.

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity |

Type of reinforcer | Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse |

Physical exercise (aerobic) |

Environmental enrichment |

||

|

ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type MSNs |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization |

Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | |

| Psychostimulant self-administration |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |

| Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

|

CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens |

No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | ||

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin |

↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | ||

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

|

Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

Dependence and withdrawal

Drug tolerance develops rapidly in amphetamine abuse (i.e., recreational amphetamine use), so periods of extended abuse require increasingly larger doses of the drug in order to achieve the same effect. According to a Cochrane review on withdrawal in individuals who compulsively use amphetamine and methamphetamine, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose." This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in roughly 88% of cases, and persist for 3–4 weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week. Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, depressed mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and lucid dreams. The review indicated that the severity of withdrawal symptoms is positively correlated with the age of the individual and the extent of their dependence. Mild withdrawal symptoms from the discontinuation of amphetamine treatment at therapeutic doses can be avoided by tapering the dose.

Overdose

An amphetamine overdose can lead to many different symptoms, but is rarely fatal with appropriate care. The severity of overdose symptoms increases with dosage and decreases with drug tolerance to amphetamine. Tolerant individuals have been known to take as much as 5 grams of amphetamine in a day, which is roughly 100 times the maximum daily therapeutic dose. Symptoms of a moderate and extremely large overdose are listed below; fatal amphetamine poisoning usually also involves convulsions and coma. In 2013, overdose on amphetamine, methamphetamine, and other compounds implicated in an "amphetamine use disorder" resulted in an estimated 3,788 deaths worldwide (3,425–4,145 deaths, 95% confidence).

| System | Minor or moderate overdose | Severe overdose |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

|

Central nervous system |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Urinary |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

Interactions

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) taken with amphetamine may result in a hypertensive crisis if taken within two weeks after last use of an MAOI type drug.

- Inhibitors of enzymes that directly metabolize amphetamine (particularly CYP2D6 and FMO3) will prolong the elimination of amphetamine and increase drug effects.

- Serotonergic drugs (such as most antidepressants) co-administered with amphetamine increases the risk of serotonin syndrome.

- Stimulants and antidepressants (sedatives and depressants) may increase (decrease) the drug effects of amphetamine, and vice versa.

- Gastrointestinal and urinary pH affect the absorption and elimination of amphetamine, respectively. Gastrointestinal alkalinizing agents increase the absorption of amphetamine. Urinary alkalinizing agents increase concentration of non-ionized species, decreasing urinary excretion.

- Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) modify the absorption of Adderall XR and Mydayis.

- Zinc supplementation may reduce the minimum effective dose of amphetamine when it is used for the treatment of ADHD.

Pharmacology

|

via AADC |

Mechanism of action

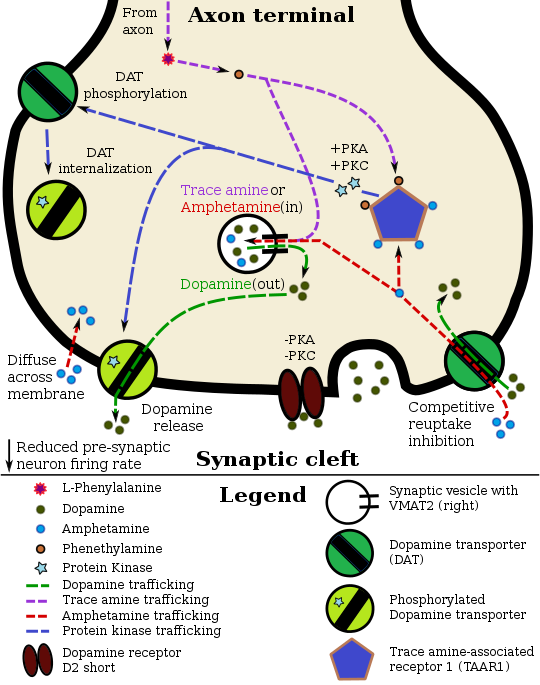

Amphetamine, the active ingredient of Adderall, works primarily by increasing the activity of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain. It also triggers the release of several other hormones (e.g., epinephrine) and neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin and histamine) as well as the synthesis of certain neuropeptides (e.g., cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) peptides). Both active ingredients of Adderall, dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, bind to the same biological targets, but their binding affinities (that is, potency) differ somewhat. Dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are both potent full agonists (activating compounds) of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and interact with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), with dextroamphetamine being the more potent agonist of TAAR1. Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces more CNS stimulation than levoamphetamine; however, levoamphetamine has slightly greater cardiovascular and peripheral effects. It has been reported that certain children have a better clinical response to levoamphetamine.

In the absence of amphetamine, VMAT2 will normally move monoamines (e.g., dopamine, histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, etc.) from the intracellular fluid of a monoamine neuron into its synaptic vesicles, which store neurotransmitters for later release (via exocytosis) into the synaptic cleft. When amphetamine enters a neuron and interacts with VMAT2, the transporter reverses its direction of transport, thereby releasing stored monoamines inside synaptic vesicles back into the neuron's intracellular fluid. Meanwhile, when amphetamine activates TAAR1, the receptor causes the neuron's cell membrane-bound monoamine transporters (i.e., the dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter, or serotonin transporter) to either stop transporting monoamines altogether (via transporter internalization) or transport monoamines out of the neuron; in other words, the reversed membrane transporter will push dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin out of the neuron's intracellular fluid and into the synaptic cleft. In summary, by interacting with both VMAT2 and TAAR1, amphetamine releases neurotransmitters from synaptic vesicles (the effect from VMAT2) into the intracellular fluid where they subsequently exit the neuron through the membrane-bound, reversed monoamine transporters (the effect from TAAR1).

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of amphetamine varies with gastrointestinal pH; it is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically over 75% for dextroamphetamine. Amphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9.9; consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium. Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in a water-soluble cationic (salt) form, and less is absorbed. Approximately 20% of amphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins. Following absorption, amphetamine readily distributes into most tissues in the body, with high concentrations occurring in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.

The half-lives of amphetamine enantiomers differ and vary with urine pH. At normal urine pH, the half-lives of dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are 9–11 hours and 11–14 hours, respectively. Highly acidic urine will reduce the enantiomer half-lives to 7 hours; highly alkaline urine will increase the half-lives up to 34 hours. The immediate-release and extended release variants of salts of both isomers reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively. Amphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH. When the urinary pH is basic, amphetamine is in its free base form, so less is excreted. When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to a high of 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively. Following oral administration, amphetamine appears in urine within 3 hours. Roughly 90% of ingested amphetamine is eliminated 3 days after the last oral dose.

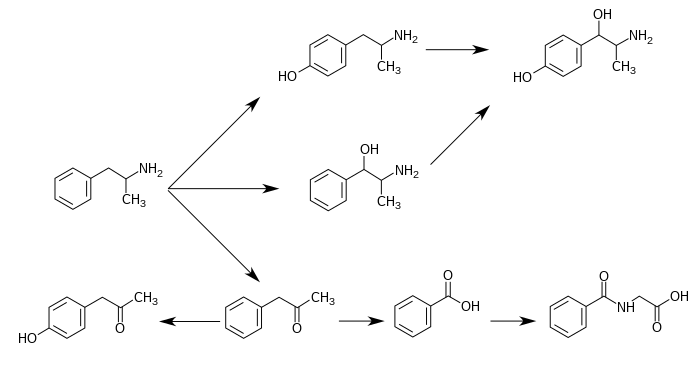

CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), butyrate-CoA ligase (XM-ligase), and glycine N-acyltransferase (GLYAT) are the enzymes known to metabolize amphetamine or its metabolites in humans. Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamphetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone. Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4-hydroxyamphetamine,4-hydroxynorephedrine, and norephedrine. The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination. The known metabolic pathways, detectable metabolites, and metabolizing enzymes in humans include the following:

|

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans

Para-

Hydroxylation Para-

Hydroxylation Para-

Hydroxylation unidentified

Beta-

Hydroxylation Beta-

Hydroxylation Oxidative

Deamination Oxidation

unidentified

Glycine

Conjugation |

Pharmacomicrobiomics

The human metagenome (i.e., the genetic composition of an individual and all microorganisms that reside on or within the individual's body) varies considerably between individuals. Since the total number of microbial and viral cells in the human body (over 100 trillion) greatly outnumbers human cells (tens of trillions), there is considerable potential for interactions between drugs and an individual's microbiome, including: drugs altering the composition of the human microbiome, drug metabolism by microbial enzymes modifying the drug's pharmacokinetic profile, and microbial drug metabolism affecting a drug's clinical efficacy and toxicity profile. The field that studies these interactions is known as pharmacomicrobiomics.

Similar to most biomolecules and other orally administered xenobiotics (i.e., drugs), amphetamine is predicted to undergo promiscuous metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota (primarily bacteria) prior to absorption into the blood stream. The first amphetamine-metabolizing microbial enzyme, tyramine oxidase from a strain of E. coli commonly found in the human gut, was identified in 2019. This enzyme was found to metabolize amphetamine, tyramine, and phenethylamine with roughly the same binding affinity for all three compounds.Related endogenous compounds

Amphetamine has a very similar structure and function to the endogenous trace amines, which are naturally occurring neuromodulator molecules produced in the human body and brain. Among this group, the most closely related compounds are phenethylamine, the parent compound of amphetamine, and N-methylphenethylamine, an isomer of amphetamine (i.e., it has an identical molecular formula). In humans, phenethylamine is produced directly from L-phenylalanine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) enzyme, which converts L-DOPA into dopamine as well. In turn, N-methylphenethylamine is metabolized from phenethylamine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, the same enzyme that metabolizes norepinephrine into epinephrine. Like amphetamine, both phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine regulate monoamine neurotransmission via TAAR1; unlike amphetamine, both of these substances are broken down by monoamine oxidase B, and therefore have a shorter half-life than amphetamine.

History

The pharmaceutical company Rexar reformulated their popular weight loss drug Obetrol following its mandatory withdrawal from the market in 1973 under the Kefauver Harris Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act due to the results of the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) program (which indicated a lack of efficacy). The new formulation simply replaced the two methamphetamine components with dextroamphetamine and amphetamine components of the same weight (the other two original dextroamphetamine and amphetamine components were preserved), preserved the Obetrol branding, and despite it lacking FDA approval, it still made it onto the market and was marketed and sold by Rexar for many years.

In 1994, Richwood Pharmaceuticals acquired Rexar and began promoting Obetrol as a treatment for ADHD (and later narcolepsy as well), now marketed under the new brand name of Adderall, a contraction of the phrase "A.D.D. for All" intended to convey that "it was meant to be kind of an inclusive thing" for marketing purposes. The FDA cited the company for numerous significant CGMP violations related to Obetrol discovered during routine inspections following the acquisition (including issuing a formal warning letter for the violations), then later issued a second formal warning letter to Richwood Pharmaceuticals specifically due to violations of "the new drug and misbranding provisions of the FD&C Act". Following extended discussions with Richwood Pharmaceuticals regarding the resolution of a large number of issues related to the company's numerous violations of FDA regulations, the FDA formally approved the first Obetrol labeling/sNDA revisions in 1996, including a name change to Adderall and a restoration of its status as an approved drug product. In 1997 Richwood Pharmaceuticals was acquired by Shire Pharmaceuticals in a $186 million transaction.

Richwood Pharmaceuticals, which later merged with Shire plc, introduced the current Adderall brand in 1996 as an instant-release tablet. In 2006, Shire agreed to sell rights to the Adderall name for the instant-release form of the medication to Duramed Pharmaceuticals. DuraMed Pharmaceuticals was acquired by Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2008 during their acquisition of Barr Pharmaceuticals, including Barr's Duramed division.

The first generic version of Adderall IR was introduced to market in 2002. Later on, Barr and Shire reached a settlement agreement permitting Barr to offer a generic form of the extended-release drug beginning in April 2009.

Commercial formulation

Chemically, Adderall is a mixture of four amphetamine salts; specifically, it is composed of equal parts (by mass) of amphetamine aspartate monohydrate, amphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine sulfate, and dextroamphetamine saccharate. This drug mixture has slightly stronger CNS effects than racemic amphetamine due to the higher proportion of dextroamphetamine. Adderall is produced as both an immediate release (IR) and extended release (XR) formulation. As of December 2013, ten different companies produced generic Adderall IR, while Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Actavis, and Barr Pharmaceuticals manufactured generic Adderall XR. As of 2013, Shire plc, the company that held the original patent for Adderall and Adderall XR, still manufactured brand name Adderall XR, but not Adderall IR.

Comparison to other formulations

Adderall is one of several formulations of pharmaceutical amphetamine, including singular or mixed enantiomers and as an enantiomer prodrug. The table below compares these medications (based on U.S.-approved forms):

| drug | formula |

molar mass |

amphetamine base |

amphetamine base in equal doses |

doses with equal base content |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/mol) | (percent) | (30 mg dose) | ||||||||

| total | base | total | dextro- | levo- | dextro- | levo- | ||||

| dextroamphetamine sulfate | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 |

368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

73.38%

|

—

|

22.0 mg

|

—

|

30.0 mg

|

|

| amphetamine sulfate | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 |

368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

36.69%

|

36.69%

|

11.0 mg

|

11.0 mg

|

30.0 mg

|

|

| Adderall |

62.57%

|

47.49%

|

15.08%

|

14.2 mg

|

4.5 mg

|

35.2 mg

|

||||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine sulfate | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 |

368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

73.38%

|

—

|

|||

| 25% | amphetamine sulfate | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 |

368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

36.69%

|

36.69%

|

|||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine saccharate | (C9H13N)2•C6H10O8 |

480.55

|

270.41

|

56.27%

|

56.27%

|

—

|

|||

| 25% | amphetamine aspartate monohydrate | (C9H13N)•C4H7NO4•H2O |

286.32

|

135.21

|

47.22%

|

23.61%

|

23.61%

|

|||

| lisdexamfetamine dimesylate | C15H25N3O•(CH4O3S)2 |

455.49

|

135.21

|

29.68%

|

29.68%

|

—

|

8.9 mg

|

—

|

74.2 mg

|

|

| amphetamine base suspension | C9H13N |

135.21

|

135.21

|

100%

|

76.19%

|

23.81%

|

22.9 mg

|

7.1 mg

|

22.0 mg

|

|

Society and culture

Legal status

- In Canada, amphetamines are in Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, and can only be obtained by prescription.

- In Japan, the use, production, and import of any medicine containing amphetamines is prohibited.

- In South Korea, amphetamines are prohibited.

- In Taiwan, amphetamines including Adderall are Schedule 2 drugs with a minimum five years prison term for possession. Only Ritalin can be legally prescribed for treatment of ADHD.

- In Thailand, amphetamines are classified as Type 1 Narcotics.

- In the United Kingdom, amphetamines are regarded as Class B drugs. The maximum penalty for unauthorized possession is five years in prison and an unlimited fine. The maximum penalty for illegal supply is 14 years in prison and an unlimited fine.

- In the United States, amphetamine is a Schedule II prescription drug, classified as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant.

- Internationally, amphetamine is in Schedule II of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Shortages

In February 2023, news organizations began reporting on shortages of Adderall in the United States that have lasted for over five months. The Food and Drug Administration first reported the shortage in October 2022.

- Image legend

External links

- "Amphetamine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Amphetamine sulfate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Amphetamine aspartate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Dextroamphetamine saccharate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Amphetamine". MedlinePlus.

- "Buy Adderall Online". Drug Information Portal. U.S. Pharmacy Store.

| Phenethylamines |

|

|---|---|

| Amphetamines |

|

| Phentermines |

|

| Cathinones |

|

| Phenylisobutylamines | |

| Phenylalkylpyrrolidines | |

|

Catecholamines |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Adamantanes | |

|---|---|

| Adenosine antagonists | |

| Alkylamines | |

| Ampakines | |

| Arylcyclohexylamines | |

| Benzazepines | |

| Cathinones |

|

| Cholinergics |

|

| Convulsants | |

| Eugeroics | |

| Oxazolines | |

| Phenethylamines |

|

| Phenylmorpholines | |

| Piperazines | |

| Piperidines |

|

| Pyrrolidines | |

| Racetams | |

| Tropanes |

|

| Tryptamines | |

| Others |

|

| CNS stimulants | |

|---|---|

| Non-classical CNS stimulants |

|

|

α2-adrenoceptor agonists |

|

| Antidepressants | |

| Miscellaneous/others | |

| Related articles |

|

| TAAR1 |

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAAR2 |

|

||||||||||

| TAAR5 |

|

||||||||||

† References for all endogenous human TAAR1 ligands are provided at List of trace amines

‡ References for synthetic TAAR1 agonists can be found at TAAR1 or in the associated compound articles. For TAAR2 and TAAR5 agonists and inverse agonists, see TAAR for references.

| |||||||||||