Announcement of polio vaccine success

The announcement of the polio vaccine's safety and effectiveness was on April 12, 1955, by Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., of the University of Michigan, the monitor of the test results. Within minutes of his announcement to the audience of scientists and reporters, news of the event was carried coast to coast by wire services and radio and television newscasts. When the vaccine was announced as successful, therefore, it led to spontaneous celebrations across the United States. It was the world's first successful polio vaccine, declared “safe, effective, and potent.” It was possibly the most significant biomedical advance of the past century.

In 1954, the year leading up to the announcement, polio was killing more American children than any other infectious disease. Jonas Salk's vaccine was made ready for its third and final field tests. It became the most elaborate program of its kind in history, involving 20,000 physicians and public health officers, 64,000 school personnel, and 220,000 volunteers. At least one hundred million people had contributed to the March of Dimes, and seven million people had donated their time and labor.

Even before the announcement, optimism and hope were so widespread that the Polio Fund in the U.S. had already contracted to purchase enough of the Salk vaccine to immunize 9,000,000 children and pregnant women the following year. And around the world, the official news prompted an immediate international rush to vaccinate.

Test results announced

Clearly a momentous and historic advance in the protection of human wellbeing.

Iain Macleod, Britain's Minister Health

On April 12, 1955, Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., of the University of Michigan, the monitor of the test results, "declared the vaccine to be safe and effective." The announcement was made at the University of Michigan, exactly 10 years to the day after the death of President Roosevelt, who himself was crippled by polio. As the world's first successful polio vaccine, it was declared “safe, effective, and potent.” Some medical experts called it "arguably the most significant biomedical advance of the past century."

Five hundred people, including 150 press, radio, and television reporters, filled the room; 16 television and newsreel cameras stood on a long platform at the back; 54,000 physicians, sitting in movie theaters across the country, watched the broadcast on closed-circuit television.Eli Lilly, a major pharmaceutical company, paid $250,000 to broadcast the event. Americans turned on their radios to hear the details, department stores set up loudspeakers, and judges suspended trials so that everyone in the courtroom could hear. Actor Robert Redford, who was 11-years-old at the time and a victim of polio, called it "earth-shattering news." Europeans listened on the Voice of America.Paul Offit describes the event in a documentary film:

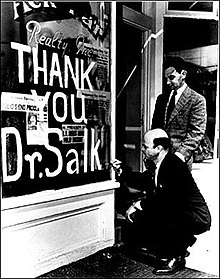

- "The presentation was numbing, but the results were clear: the vaccine worked. Inside the auditorium, Americans tearfully and joyfully embraced the results. By the time Thomas Francis stepped down from the podium, church bells were ringing across the country, factories were observing moments of silence, synagogues and churches were holding prayer meetings, and parents and teachers were weeping. One shopkeeper painted a sign on his window: Thank you, Dr. Salk. 'It was as if a war had ended', one observer recalled."

"The report," wrote the New York Times, "was a medical classic." Dr. Francis reported that the vaccinations had been 80 to 90 percent effective on the basis of results in eleven states. Overall, the vaccine was administered to over 440,000 children in forty-four states, three Canadian provinces and in Helsinki, Finland, and the final report required the evaluation of 144,000,000 separate items of information. After the announcement, when asked whether the effectiveness of the vaccine could be improved, Salk said, "Theoretically, the new 1955 vaccines and vaccination procedures may lead to 100 percent protection from paralysis of all those vaccinated."

Initial reactions

Within minutes of Francis's declaration that the vaccine was safe and effective, the news of the event was carried world-wide by wire services and radio and television newscasts.

These reactions by the public and media were seen as justified due to the history of the disease. At the start of the 20th century, for instance, during the 1914 and 1919 polio epidemics in the United States, physicians and nurses made house-to-house searches to identify all infected persons. Children suspected of being infected were taken to hospitals and the child's family was quarantined until they were no longer potentially infectious, even if it meant they could not go to their child's funeral if the child died in the hospital.

New York alone had 9,023 cases in 1916, of which 2,448 (28%) resulted in death and a larger number in paralysis. Over the years, as more states began recording instances of the disease, the numbers of victims grew larger. Nearly 58,000 cases of polio were reported in 1952, with 3,145 people dying and 21,269 left with mild to disabling paralysis.

The "public reaction was to a plague", said historian William O'Neill. Citizens of urban areas were terrified each summer when the epidemic was at its worst. "Apart from the atomic bomb," stated a PBS documentary, "America's greatest fear was polio."

It meant that scientists and political leaders were in a frantic race to prevent or cure the disease. Basil O'Connor, president of the American Red Cross, was tasked by President Roosevelt to do whatever was necessary to see that a vaccine was created. That included allowing the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, the primary fundraising organization, to go into debt to help Salk complete his research and testing. O'Connor's devotion to this task became almost obsessive when his daughter, a mother of five, told him that she had contracted the illness, saying, "I've gotten some of your polio." "Salk worked sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, for years," wrote Dennis Denenberg.

Nothing short of the overthrow of the Communist regime in the Soviet Union could bring such rejoicing to the hearths and homes of America as the historic announcement last Tuesday that the 166-year war against paralytic poliomyelitis is almost certainly at an end.

When Salk's vaccine was announced as successful, it led to spontaneous celebrations across the United States: "Business came to a halt as the news spread," states Bookchin. The Eisenhower administration made plans to present Salk a special presidential medal designating him "a benefactor of mankind" in a Rose Garden ceremony.

It was also declared "a victory for the whole nation." Jonas Salk became "world famous overnight and was showered with awards", said historian William O'Neill. He received a Presidential Citation, the nation's first Congressional Medal for Distinguished Civilian Service, and a large number of honorary degrees and related honors.

According to O'Neill, April 12 had almost become a national holiday. He recalls:

People observed moments of silence, rang bells, honked horns, blew factory whistles, fired salutes, kept their red lights red in brief periods of tribute, took the rest of the day off, closed their schools or convoked fervid assemblies therein, drank toasts, hugged children, attended church, smiled at strangers, and forgave enemies."

Results

Six months before Salk's announcement, optimism and hope were so widespread that the Polio Fund in the United States had already contracted to purchase enough of the Salk vaccine to immunize 9,000,000 children and pregnant women the following year. And around the world, the official news prompted an immediate international rush to vaccinate. Medical historian Debbie Bookchin notes that Israel had committed to the Salk vaccine just days before the final report was released, and soon after, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, West Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium all announced plans to either immediately begin polio immunization campaigns using Salk's vaccine or to gear up to quickly do so.

By the summer of 1957, over two years later, 100,000,000 doses had been distributed throughout the United States and reported complications were rare. Scientists from other nations reported similar experiences: Denmark, for example, reported only a few cases from 2,500,000 who were vaccinated. Australia reported virtually no polio during her past summer season.

Other countries where the vaccine was not yet in use suffered continued epidemics, however. In 1957, Hungary, for example, reported a severe epidemic requiring emergency international assistance. By the first half of the year they had 713 reported cases and a death rate of 6.6%, and the peak infection months of summer were still ahead. Canada sent a shipment of vaccines to Hungary by a refrigerated plane, and Britain and Sweden sent iron lungs. A few years later, during a polio outbreak in Canada, "masked bandits" stole 75,000 Salk vaccine shots from a Montreal university research center.

Just months after the vaccine's success was announced, American President Eisenhower signed the Polio Vaccination Assistance Act of 1955, to ensure the vaccine would be distributed to the public. As a result, 30 million inoculations were given to children in the United States within a year, leading polio cases to fall by almost half during that time. By 1962, the number of cases had fallen to less than 1,000. In 1965, with total cases having dropped to 121, U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry called it an "historic triumph of preventive medicine — unparalleled in history." In 1979 the United States was declared polio-free.

Globally, by the end of 1990 an estimated 500,000 annual cases worldwide of paralysis were prevented as result of the polio vaccine immunization programs carried out by WHO, UNICEF, and many other organizations. In developing countries, estimates ran as high as 350,000 cases each year in 1988. As a result, in 2002, more than 500 million children were immunized in 93 countries, and by December 2002, there were only 1,924 cases worldwide, mainly in India.