Clerical celibacy in the Catholic Church

Clerical celibacy is the discipline within the Catholic Church by which only unmarried men are ordained to the episcopate, to the priesthood in the Latin Church (with some particular exception and in some autonomous particular Churches, and similarly to the diaconate. In other autonomous particular churches, the discipline applies only to the episcopate.

The Catholic particular church which principally follows this discipline is the Latin Church, this does not apply to the Eastern Catholic Churches which permit married men to be ordained to priesthood with the exception of the Ethiopian Catholic Church. All particular Churches of the Catholic Church require Bishops to be celibate as was the practice of the ancient Church as Bishops were chosen from monastics who always practice celibacy.

In this context, "celibacy" retains its original meaning of "unmarried". Though even the married may observe abstinence from sexual intercourse, the obligation to be celibate is seen as a consequence of the obligation to observe perfect and perpetual continence for the sake of the Kingdom of heaven. Advocates see clerical celibacy as "a special gift of God by which sacred ministers can more easily remain close to Christ with an undivided heart, and can dedicate themselves more freely to the service of God and their neighbour."

In February 2019, the Vatican acknowledged that the policy has not always been enforced and that rules had been secretly established by the Vatican to protect non-celibate clergy who violated their vows of celibacy. Some clergy have also been allowed to retain their clerical state after fathering children. Some Catholic clergy who violated their vows of celibacy also have maintained their clerical status after secretly marrying women. Prefect for the Congregation for Clergy Cardinal Beniamino Stella also acknowledged that child support and transfer have been two common ways for such clergy to maintain their clerical status.

Description

The Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, in general, rule out ordination of married men to the episcopate, and marriage after priestly ordination. Throughout the Catholic Church, East as well as West, a priest may not marry. In the Eastern Catholic Churches, a married priest is one who married before being ordained.

The Catholic Church considers the law of clerical celibacy to be not a doctrine, but a discipline. Exceptions are sometimes made, especially in the case of married male Lutheran, Anglican and other Protestant clergy who convert to the Catholic Church, and the discipline could, in theory, be changed for all ordinations to the priesthood.

Theological and scriptural foundations

Theologically, the Roman Catholic Church teaches that priesthood is a ministry conformed to the life and work of Jesus Christ. Priests as sacramental ministers act in persona Christi, that is in the mask of Christ. Thus the life of the priest conforms, the Church believes, to the chastity of Christ himself. The sacrifice of married life is for the "sake of the Kingdom" (Luke 18:28–30, Matthew 19:27–30), and to follow the example of Jesus Christ in being "married" to the Church, viewed by Catholicism and many Christian traditions as the "Bride of Christ" (following Ephesians 5:25–33 and Revelation 21:9, together with the spousal imagery at Mark 2:19–20; cf. Matthew 9:14–15).

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) in Salt of the Earth saw this practice as based on Jesus' words in Matthew 19:12: "Some are eunuchs because they were born that way; others were made that way by men; and others have renounced marriage because of the kingdom of heaven. The one who can accept this should accept it." He linked this celibacy "because of the kingdom of heaven" with God's choice to confer the Old Testament priesthood on a specific tribe, that of Levi, which unlike the other tribes received no land from God, but which had "God himself as its inheritance" (Numbers 1:48–53).

Paul, within a context of having "no command from the Lord" (1 Cor 7:25), recommends celibacy, but acknowledges that it is not God's gift to all within the church: "For I wish that all men were even as I myself. But each one has his own gift from God, one in this manner and another in that. But I say to the unmarried and to the widows: It is good for them if they remain even as I am, ... I want you to be without care. He who is unmarried cares for the things of the Lord—how he may please the Lord. But he who is married cares about the things of the world—how he may please his wife. There is a difference between a wife and a virgin. The unmarried woman cares about the things of the Lord, that she may be holy both in body and in spirit. But she who is married cares about the things of the world—how she may please her husband. And this I say for your own profit, not that I may put a leash on you, but for what is proper, and that you may serve the Lord without distraction" (1 Corinthians 7:7–8, 7:32–35). Peter Brown and Bart D. Ehrman speculate that for early Christians celibacy had to do with the "imminent end of the age" (1 Corinthians 7:29–31).

Historical origins

In the earliest years of the church, the clergy were largely married men. C. K. Barrett points to 1 Cor 9:5 as clearly indicating that "apostles, like other Christians, have a right to be (and many of them are) married" and the right for their wife to be "maintained by the communities in which they [the apostles] are working." However, Paul himself was celibate at the time of his ministry, and there is no consensus that inclusion among the requirements for candidacy to the office of "overseer" of being "the husband of one wife" meant that celibate Christians were excluded.

Studies by some Catholic scholars, such as the Ukrainian Roman Cholij and Christian Cochini, have argued for the theory that, in early Christian practice, married men who became priests—they were often older men, "elders"—were expected to live in complete continence, refraining permanently from sexual relations with their wives. When at a later stage it was clear that not all did refrain, the Western Church limited ordination to unmarried men and required a commitment to lifelong celibacy, while the Eastern Churches relaxed the rule, so that Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches now require their married clergy to abstain from sexual relations only for a limited period before celebrating the Eucharist. The Church in Persia, which in the fifth century became separated from the Church described as Orthodox or Catholic, decided at the end of that century to abolish the rule of continence and allow priests to marry, but recognized that it was abrogating an ancient tradition. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, whose separation, along with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, came slightly later, allows deacons (who are ordained when they are boys) to marry after ordination, but not priests: any future priests who wish to marry must do so before becoming priests. The Armenian Apostolic Church, which also belongs to Oriental Orthodoxy, while technically prohibiting, like the Eastern Orthodox Church, marriage after ordination to the sub-diaconate, has generally let this rule fall into disuse and allows deacons to marry up to the point of their priestly ordination, thus continuing to maintain the traditional exclusion of marriage by those who are priests. This theory would explain why all the ancient Christian Churches of both East and West, with the one exception mentioned, exclude marriage after priestly ordination, and why all reserve the episcopate (seen as a fuller form of priesthood than the presbyterate) for the celibate.

Some Catholic scholars, such as Jesuits Peter Fink and George T. Dennis of Catholic University of America, have argued that we cannot know if priests in early Christianity practised sexual abstinence. Dennis says "there is simply no clear evidence of a general tradition or practice, much less of an obligation, of priestly celibacy-continence before the beginning of the fourth century." Fink says that a primary book used to support apostolic origins of priestly celibacy "remains a work of interpretation. There are underlying premises that seem to hold firm in this book but which would not stand up so comfortably to historical scrutiny."

The earliest textual evidence of the forbidding of marriage to clerics and the duty of those already married to abstain from sexual contact with their wives is in the fourth-century decrees of the Synod of Elvira and the later Council of Carthage (390). According to some writers, this presumed a previous norm, which was being flouted in practice.

- Synod of Elvira (c. 305)

- (Canon 33): "It is decided that marriage be altogether prohibited to bishops, priests, and deacons, or to all clerics placed in the ministry, and that they keep away from their wives and not beget children; whoever does this shall be deprived of the honor of the clerical office."

- Council of Carthage (390)

- (Canon 3): "It is fitting that the holy bishops and priests of God as well as the Levites, i.e. those who are in the service of the divine sacraments, observe perfect continence, so that they may obtain in all simplicity what they are asking from God; what the Apostles taught and what antiquity itself observed, let us also endeavour to keep.... It pleases us all that bishop, priest and deacon, guardians of purity, abstain from conjugal intercourse with their wives, so that those who serve at the altar may keep a perfect chastity."

Among the early Church statements on the topic of sexual continence and celibacy are the Directa and Cum in unum decretals of Pope Siricius (c. 385), which asserted that clerical sexual abstinence was an apostolic practice that must be followed by ministers of the church.

The writings of Saint Ambrose (died 397) also show that the requirement that priests, whether married or celibate, should be continent was the established rule. To the married clergy who, "in some out-of-the-way places", claimed, on the model of the Old Testament priesthood, the right to father children, he recalled that in Old Testament times even lay people were obliged to observe continence on the days leading to a sacrifice, and commented: "If such regard was paid in what was only the figure, how much ought it to be shown in the reality!" Yet more sternly he wrote: "(Saint Paul) spoke of one who has children, not of one who begets children."

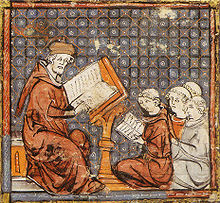

Medieval Christendom

Beyond the fact that clerical celibacy functioned as a spiritual discipline, it also was guarantor of the independence of the Church and of its essential dimension as a spiritual institution ordered toward ends beyond the competence and authority of temporal rulers.

During the decline of the Roman Empire, Roman authority in western Europe completely collapsed. However, the city of Rome, under the guidance of the Catholic Church, still remained a centre of learning and did much to preserve classical Roman culture in Western Europe. The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and the Latin West. Philosopher Will Durant argues that certain prominent features of Plato's ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of the medieval Church in Europe:

The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church. In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians].... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them....

In his book The Ruling Class, Gaetano Mosca wrote of the medieval Church and its structure:

[Although] the Catholic Church has always aspired to a preponderant share in political power, it has never been able to monopolize it entirely, because of two traits, chiefly, that are basic in its structure. Celibacy has generally been required of the clergy and of monks. Therefore no real dynasties of abbots and bishops have ever been able to establish themselves.... Secondly,...the ecclesiastical calling has by its very nature never been strictly compatible with the bearing of arms.

It is sometimes claimed that celibacy became mandatory for Latin Church priests only in the eleventh century; but others say, for instance: "(I)t may fairly be said that by the time of St. Leo the Great (440–61) the law of celibacy was generally recognized in the West," and that the eleventh-century regulations on this matter, as on simony, should obviously not be interpreted as meaning that either non-celibacy or simony were previously permitted. However there is abundant documentation that up to 12th century many priests in Europe were married and that their sons would often follow their path which made the reforms difficult to implement. The last married Pope was Adrian II (r. 867–872), who was married to Stephania, with whom he had a daughter.

Reformation period

Celibacy as a requirement for ordination to the priesthood (in the Western Church) and to the episcopate (in East as well as in West) and declaring marriages of priests invalid (in both East and West) were important points of disagreement during the Protestant Reformation, with the Reformers arguing that these requirements were contrary to Biblical teaching in 1 Timothy 4:1–5, Hebrews 13:4, and 1 Corinthians 9:5, and implied a degradation of marriage, and were one reason for "many abominations" and for widespread sexual misconduct within the clergy at the time of the Reformation. The doctrinal view of the Reformers on this point was reflected in the marriages of Zwingli in 1522, Luther in 1525, and Calvin in 1539; in England, the married Thomas Cranmer was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533. Both of these actions, marriage after ordination to the priesthood and consecration of a married man as a bishop, went against the long-standing tradition of the Church in the East as well as in the West. In the Church of Sweden, a Lutheran Church, the vow of clerical celibacy, along with vowing fidelity to a motherhouse and a life of poverty, was required of deaconesses until the 1960s; this vow of celibacy was made optional and deacons/deaconesses in the Church of Sweden may be married in present-day practice.

Celibacy in the present-day Church

Celibacy of deacons

Following recommendations made at the Second Vatican Council, the Latin Church now admits married men of mature age to ordination as deacons, to remain permanently as deacons and not as part of the process by which aspirants are temporarily deacons on their way to priestly ordination. The change was effected by Pope Paul VI's motu proprio Sacrum diaconatus ordinem of 18 June 1967. A candidate for ordination to the permanent diaconate must have reached the age of 25 if unmarried or the age of 35 if married (or higher if established by the Conference of Bishops), and must have the written consent of his wife.

Ordination even to the diaconate is an impediment to a later marriage (for example, if a man who was already married by the time of ordination to the diaconate subsequently becomes a widower), though special dispensation can be received for remarriage under extenuating circumstances.

Celibacy of priests

Debate on celibacy of priests

Garry Wills, in his book Papal Sin: Structures of Deceit, argued that the imposition of celibacy among Catholic priests played a pivotal role in the cultivation of the Church as one of the most influential institutions in the world. In his discussion concerning the origins of the said policy, Wills mentioned that the Church drew its inspiration from the ascetics, monks who devote themselves to meditation and total abstention from earthly wealth and pleasures in order to sustain their corporal and spiritual purity, after seeing that its initial efforts in propagating the faith were fruitless. The rationale behind such strict policy is that it significantly helps the priests perform well in their religious services while at the same time following the manner in which Jesus Christ lived his life. Moreover, the author also mentioned that although the said policy insists on helping priests focus more on ecclesiastical duties, it also enabled the Church to control the wealth amassed by the clerics through their various religious activities, hence contributing to the growing power of the institution.

The Latin Church discipline continues to be debated for a variety of reasons.

First, many believe celibacy was not required of the apostles. Peter himself had a wife at some time, whose mother Jesus healed of a high fever. And 1 Corinthians 9:5 is commonly interpreted as saying that years later, Peter and other apostles were accompanied by their wives. However, on the basis especially of Luke 18:28–30, others think the apostles left their wives, and that the women mentioned in 1 Corinthians as accompanying some apostles were "holy women, who, in accordance with Jewish custom, ministered to their teachers of their substance, as we read was the practice with even our Lord himself."

Second, this requirement excludes a great number of otherwise qualified men from the priesthood, qualifications which according to the defenders of celibacy should be determined not by merely human hermeneutics but by the hermeneutics of the divine. Supporters of clerical celibacy answer that God only calls men to the priesthood if they are capable. Those who are not called to the priesthood should seek other paths in life since they will be able to serve God better there. Therefore, to the supporters of celibacy no one who is called is excluded.

Third, some say that resisting the natural sexual impulse in this way is unrealistic and harmful for a healthy life. Sexual scandals among priests, especially homosexuality and pedophilia, the defenders say, are a breach of the Church's discipline, not a result of it, especially since only a small percentage of priests have been involved.

Fourth, it is said that mandatory celibacy distances priests from this experience of life, compromising their moral authority in the pastoral sphere, although its defenders argue that the Church's moral authority is rather enhanced by a life of total self-giving in imitation of Christ, a practical application of the Vatican II teaching that "man cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself."

In 1970, nine German theologians, including Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI), signed a letter calling for a new discussion of the law of celibacy, though refraining from making a statement as to whether the law of celibacy should in fact be changed.

In 2011, hundreds of German, Austrian, and Swiss theologians (249 as of 15 February 2011) signed a letter calling for married priests, as well as for women in Church ministry.

Since the Second Vatican Council

During and after the Council, the Magisterium of the Catholic Church has repeatedly re-affirmed the permanent value of the discipline of obligatory clerical celibacy in the Latin Church. Pope John Paul II wrote in 1992:

"The synod fathers clearly and forcefully expressed their thought on this matter in an important proposal which deserves to be quoted here in full: "While in no way interfering with the discipline of the Oriental churches, the synod, in the conviction that perfect chastity in priestly celibacy is a charism, reminds priests that celibacy is a priceless gift of God for the Church and has a prophetic value for the world today. This synod strongly reaffirms what the Latin Church and some Oriental rites require, that is that the priesthood be conferred only on those men who have received from God the gift of the vocation to celibate chastity (without prejudice to the tradition of some Oriental churches and particular cases of married clergy who convert to Catholicism, which are admitted as exceptions in Pope Paul VI's encyclical on priestly celibacy, no. 42). The synod does not wish to leave any doubts in the mind of anyone regarding the Church's firm will to maintain the law that demands perpetual and freely chosen celibacy for present and future candidates for priestly ordination in the Latin rite."

He added that the "unchanging" essence of ordination "configures the priest to Jesus Christ the Head and Spouse of the Church." Thus, he said, "The Church, as the Spouse of Jesus Christ, wishes to be loved by the priest in the total and exclusive manner in which Jesus Christ her Head and Spouse loved her."

There has never been any doubt, however, that it is an ecclesiastical discipline, as the Council Fathers explicitly recognised when they stated that "it is not demanded by the very nature of the priesthood." Pope John Paul II took up this theme when he said at a public audience on 17 July 1993 that celibacy "does not belong to the essence of priesthood." He went on to speak of its aptness for, and its congruence with, the requirements of sacred orders, asserting that the discipline "enters into the logic of [priestly] consecration."

Yet some commentators have argued for the possibility that married men of proven seriousness and maturity (viri probati, taking up a phrase which appears in the first-century First Epistle of Clement in a different context) might be ordained to a localized and modified form of the priesthood. The topic of viri probati was raised by some participants in discussions at Ordinary General Assembly XI of the Synod of Bishops held at the Vatican in October 2005 on the theme of the Eucharist, but it was rejected as a solution for the insufficiency of priests.

Pope Francis

Pope Francis shared his views on celibacy, and the possibility of church discussion on the topic, when he was the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, recorded in the book On Heaven and Earth, a record of conversations conducted with a Buenos Aires rabbi. He commented that celibacy "is a matter of discipline, not of faith. It can change" but added: "For the moment, I am in favor of maintaining celibacy, with all its pros and cons, because we have ten centuries of good experiences rather than failures.... Tradition has weight and validity." He said that now the rule must be strictly adhered to, and any priest who cannot obey it "has to leave the ministry."National Catholic Reporter Vatican analyst, Jesuit Thomas J. Reese, called Bergoglio's use of "conditional language" regarding the rule of celibacy "remarkable." He said that phrases like "for the moment" and "for now" are "not the kind of qualifications one normally hears when bishops and cardinals discuss celibacy."

In a conversation with Bishop Erwin Krautler about mandatory celibacy on 4 April 2014, the Pope also spoke about a possible mechanism for a change starting with national bishop conferences. These conferences would

seek and find consensus on reform and we should then bring up our suggestions for reform in Rome. ...The pope explained that he could not take everything in hand personally from Rome. We local bishops, who are best acquainted with the needs of our faithful, should be ‘corajudos,’ that is ‘courageous’ in Spanish, and make concrete suggestions.... It was up to the bishops to make suggestions, the pope said again.

In 2018 Francis showed that he wanted the topic discussed, beginning with remote areas like Amazonia that have a shortage of priests.

In October 2018, Belgian Catholic bishop conference supported married priests.

Different German catholic bishops like Ulrich Neymeyr (Roman Catholic Diocese of Erfurt), Reinhard Marx (Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising),Peter Kohlgraf (Roman Catholic Diocese of Mainz), Helmut Dieser (Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen),Franz Jung (Roman Catholic Diocese of Würzburg),Franz-Josef Overbeck (Roman Catholic Diocese of Essen) and Karl-Heinz Wiesemann (Roman Catholic Diocese of Speyer) support exceptions from clerical celibacy for priests. Also German bishop Georg Bätzing (Roman Catholic Diocese of Limburg) said, there should be also married priests in Roman Catholic Church. The same opinion was also expressed by German bishop Gerhard Feige (Roman Catholic Diocese of Magdeburg) in February 2019 and German bishop Heiner Wilmer (Roman Catholic Diocese of Hildesheim) in February 2019. In March 2019, German bishop Stefan Oster (Roman Catholic Diocese of Passau) said, there can be also married priests in Roman Catholic Church. In Lingen the German catholic bishops started a reform group under leadership of bishop Felix Genn (Roman Catholic Diocese of Münster) to talk over a reform of clerical celibacy for priests and if married priests should also be allowed. In April 2019, Austrian bishop Christoph Schönborn (Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna) said, there can be clerical celibacy priests and also married priests in Roman Catholic Church. In June 2019, German bishop Franz-Josef Bode (Roman Catholic Diocese of Osnabrück) said, there can be clerical celibacy priests and also married priests in Roman Catholic Church. In December 2019, German bishop Heinrich Timmerevers answered also, there can be married priests in Catholic Church.

In November 2019, the Amazonassynode in Rome voted by 128 to 41 votes in favour for married priests in Latin America. Following the synod, Pope Francis rejected the proposal in his post-synodal apostolic exhortation Querida Amazonia.

On March 9, 2023 again in Frankfurt am Main at Synodal Path around 75 percentage of German Roman-Catholic bishops supported married priests and want a free celibacy for priests.

Exceptions to the rule of priestly celibacy

Exceptions to the rule of celibacy for priests of the Latin Church are sometimes granted by authority of the Pope, when married Protestant clergy become Catholic. Thus married Anglicans have been ordained to the Catholic priesthood in personal ordinariates and through the United States Pastoral Provision. Because the rule of celibacy is an ecclesiastical law and not a doctrine, it can, in principle, be changed at any time by the Pope. Nonetheless, both Pope Benedict XVI and his predecessors have spoken clearly of their understanding that the traditional practice was not likely to change.

Father Richard McBrien, a controversial voice within the Church, argued that the existence of these exceptions, coupled with a declining number of priests in active ministry (per McBrien's North America and in Europe) and reported cases of non-observance of the norm will keep the subject in the spotlight. However, the number of priests worldwide has been increased from about 405,000 in 1995 to 415,000 in 2016, reversing the previous downward tendency from about 420,000 in 1970 to 403,000 in 1990.

Lack of enforcement

Despite the Latin Church's historical practice of priestly celibacy, there have been Catholic priests throughout the centuries who have engaged in sexual relations through the practice of concubinage.

One notable example was former EWTN priest Francis Mary Stone, who was also revealed to have privately maintained his clerical status after violating his vow of celibacy and also fathering a child with an employee at EWTN when he was serving as a host of the network's show Life on the Rock. After these revelations were made public, Stone was at first only suspended from public ministry. He was later accused of sexually abusing the son he fathered with this employee, but was later acquitted. By 2018, it was reported that Stone was still only suspended from his religious order and was not yet acknowledged to have been removed.

On 18 February 2019, the Vatican acknowledged that the celibacy policy has not always been enforced. Some of the Catholic clergy who violated their vow of celibacy had also fathered children as well. It was also revealed that during the course of history, rules were secretly established by the Vatican to protect clergy who had violated the celibacy policy, including those who fathered children. Some people who were fathered by Catholic clergy also made themselves public as well.

In an interview with Vatican News editor Andrea Tornielli on 27 February 2019, Prefect of Congregation of the Clergy Beniamino Stella revealed that his Congregation manages matters concerning priests who violate their vows of celibacy. Regarding violation of the celibacy policy, Stella stated "In such cases there are, unfortunately, Bishops and Superiors who think that, after having provided economically for the children, or after having transferred the priest, the cleric could continue to exercise the ministry."

Some clergy who violated the celibacy policy, which also forbids marriage for clergy who did not convert from the Protestant faiths, such as Lutheranism or Anglicanism, have also maintained their clerical status after marrying women in secret. One example was shown in the Diocese of Greensburg in Pennsylvania, where a priest maintained his clerical status after marrying a girl he impregnated. In 2012, Kevin Lee, a priest in Australia, revealed that he had maintained his clerical status after being secretly married for a full year and that church leaders were aware of his secret marriage, but disregarded the celibacy policy. The same year, it was revealed that former Los Angeles Auxiliary Bishop Gabino Zavala had privately fathered two children and had "more than a passing relationship" with their mother, who had two separate pregnancies, before he resigned from his post as Auxiliary Bishop and from the Catholic clergy.

Eastern Catholic churches

In general, the Eastern Catholic Churches allow ordination of married men as priests. Within the lands of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest Eastern Rite Catholic Church, priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a tightly-knit hereditary caste. In North America, by the provisions of the decree Cum data fuerit, and for fear that married priests would create scandal among Latin Church Catholics, Eastern Catholic bishops were directed to ordain only unmarried men. This ban, which some bishops determined to be null in various circumstances or at times or simply decided not to enforce, was finally rescinded by a decree of June 2014. Similarly, the Maronite Church does not demand celibacy vows from its deacons or parish priests; their monks, however, are celibate, as well as their bishops who are normally selected from celibate priests and sometimes from the monasteries. The current Patriarch of the Maronite Church is originally a monk in the Mariamite Maronite Order.

A condition for becoming an Eastern Catholic bishop is to be unmarried or a widower.

See also

- Children of the Ordained

- Clerical marriage

- Christian monks, religious sisters and nuns make vows of celibacy.

- List of sexually active popes

Further reading

- Priestly Celibacy Today—book by Thomas McGovern

- Priestly celibacy in patristics and in the history of the Church—Roman Cholij

- Priestly Celibacy. Ecclesiastical Institution or Apostolic Tradition?—Cesare Bonivento

- The Case for Clerical Celibacy:Its Historical Development and Theological Foundations Archived 13 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine—Alfons Stickler

- Celibacy Dates Back to the Apostles—Fr. Anthony Zimmerman, STD

- The Ancient Tradition of Clerical Celibacy—Mary R. Schneider (Ignatius Press)

- Celibacy in the Old Testament and Jewish Tradition—by Br. Anthony Opisso, M.D.

- Francis Speaks, Scalfari Transcribes, Brandmüller Shreds—by Sandro Magister

- "Why Does the Catholic Church Insist on Celibacy?" by Rafael Domingo

External links

- Encyclical Sacerdotalis caelibatus—Pope Paul VI

- The radical importance of the graced gift of priestly celibacy—Congregation for the Clergy

|

Patriarchates (by order of precedence) |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

|

||||||

| Language | |||||||

|

Liturgical rites Liturgical days |

|

||||||

| See also | |||||||

| |||||||