Deep brain stimulation

| Deep brain stimulation | |

|---|---|

| |

| MeSH | D046690 |

| MedlinePlus | 007453 |

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical procedure involving the placement of a medical device called a neurostimulator, which sends electrical impulses, through implanted electrodes, to specific targets in the brain (the brain nucleus) for the treatment of movement disorders, including Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and other conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and epilepsy. While its underlying principles and mechanisms are not fully understood, DBS directly changes brain activity in a controlled manner.

DBS has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for essential tremor and Parkinson's disease (PD) since 1997. DBS was approved for dystonia in 2003, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2009, and epilepsy in 2018. DBS has been studied in clinical trials as a potential treatment for chronic pain for various affective disorders, including major depression. It is one of few neurosurgical procedures that allow blinded studies.

Medical use

Parkinson's disease

DBS is used to manage some of the symptoms of Parkinson's disease that cannot be adequately controlled with medications. PD is treated by applying high-frequency (> 100 Hz) stimulation to three target structures, namely to the ventrolateral thalamus, internal pallidum, and subthalamic nucleus (STN) to mimic the clinical effects of lesioning. It is recommended for people who have PD with motor fluctuations and tremors inadequately controlled by medication, or to those who are intolerant to medication, as long as they do not have severe neuropsychiatric problems. Four areas of the brain have been treated with neural stimulators in PD. These are the globus pallidus internus, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus and the pedunculopontine nucleus. However, most DBS surgeries in routine practice target either the globus pallidus internus or the Subthalamic nucleus.

- DBS of the globus pallidus internus reduces uncontrollable shaking movements called dyskinesias. This enables a patient to take adequate quantities of medications (especially levodopa), thus leading to better control of symptoms.

- DBS of the subthalamic nucleus directly reduces symptoms of Parkinson's. This enables a decrease in the dose of anti-parkinsonian medications.

- DBS of the PPN may help with freezing of gait, while DBS of the thalamus may help with tremors. These targets are not routinely utilized.

Selection of the correct DBS target is a complicated process. Multiple clinical characteristics are used to select the target including – identifying the most troublesome symptoms, the dose of levodopa that the patient is currently taking, the effects and side-effects of current medications and concurrent problems. For example, subthalamic nucleus DBS may worsen depression and hence is not preferred in patients with uncontrolled depression.

Generally, DBS is associated with a 30–60% improvement in motor score evaluations. However, DBS is administered continuously and with fixed parameters and does not fully control motor fluctuations that characterize Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, in recent years, the concept of adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation (aDBS), a type of DBS that automatically adapts stimulation parameters to Parkinsonian symptoms, was developed. aDBS devices are currently under investigation to be adopted in clinical practice.

Tourette syndrome

DBS has been used experimentally in treating adults with severe Tourette syndrome who do not respond to conventional treatment. Despite widely publicized early successes, DBS remains a highly experimental procedure for treating Tourette's, and more study is needed to determine whether long-term benefits outweigh the risks. The procedure is well tolerated, but complications include "short battery life, abrupt symptom worsening upon cessation of stimulation, hypomanic or manic conversion, and the significant time and effort involved in optimizing stimulation parameters".

The procedure is invasive and expensive and requires long-term expert care. Benefits for severe Tourette's are inconclusive, considering the less robust effects of this surgery seen in the Netherlands. Tourette's is more common in pediatric populations, tending to remit in adulthood, so, in general, this would not be a recommended procedure for use on children. It may not always be obvious how to utilize DBS for a particular person because the diagnosis of Tourette's is based on a history of symptoms rather than an examination of neurological activity. Due to concern over the use of DBS in Tourette syndrome treatment, the Tourette Association of America convened a group of experts to develop recommendations guiding the use and potential clinical trials of DBS for TS.

Robertson reported that DBS had been used on 55 adults by 2011, remained an experimental treatment at that time, and recommended that the procedure "should only be conducted by experienced functional neurosurgeons operating in centres which also have a dedicated Tourette syndrome clinic". According to Malone et al. (2006), "Only patients with severe, debilitating, and treatment-refractory illness should be considered; while those with severe personality disorders and substance-abuse problems should be excluded." Du et al. (2010) say, "As an invasive therapy, DBS is currently only advisable for severely affected, treatment-refractory TS adults". Singer (2011) says, "pending determination of patient selection criteria and the outcome of carefully controlled clinical trials, a cautious approach is recommended". Viswanathan et al. (2012) say DBS should be used for people with "severe functional impairment that cannot be managed medically".

Epilepsy

As many as 36.3% of epilepsy patients are drug-resistant. These patients are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality. In cases where surgery is not an option, neurostimulation such as DBS, as well as vagus nerve stimulation and responsive neurostimulation can be considered. Targets other than the anterior nucleus of the thalamus have been studied for the treatment of epilepsy, such as the centromedian nucleus of the thalamus, the cerebellum and others.

Adverse effects

DBS carries the risks of major surgery, with a complication rate related to the experience of the surgical team. The major complications include hemorrhage (1–2%) and infection (3–5%).

The potential exists for neuropsychiatric side effects after DBS, including apathy, hallucinations, hypersexuality, cognitive dysfunction, depression, and euphoria. However, these effects may be temporary and related to (1) correct placement of electrodes, (2) open-loop VS closed-loop stimulation, meaning a constant stimulation or an A.I. monitoring delivery system and (3) calibration of the stimulator, so these side effects are potentially reversible.

Because the brain can shift slightly during surgery, the electrodes can become displaced or dislodged from the specific location. This may cause more profound complications such as personality changes, but electrode misplacement is relatively easy to identify using CT scan. Also, surgery complications may occur, such as bleeding within the brain. After surgery, swelling of the brain tissue, mild disorientation, and sleepiness are normal. After 2–4 weeks, a follow-up visit is used to remove sutures, turn on the neurostimulator, and program it.

Impaired swimming skills surfaced as an unexpected risk of the procedure; several Parkinson's disease patients lost their ability to swim after receiving deep brain stimulation.

Mechanisms

The exact mechanism of action of DBS is not known. A variety of hypotheses try to explain the mechanisms of DBS:

- Depolarization blockade: Electrical currents block the neuronal output at or near the electrode site.

- Synaptic inhibition: This causes an indirect regulation of the neuronal output by activating axon terminals with synaptic connections to neurons near the stimulating electrode.

- Desynchronization of abnormal oscillatory activity of neurons

- Antidromic activation either activating/blockading distant neurons or blockading slow axons

DBS represents an advance on previous treatments which involved pallidotomy (i.e., surgical ablation of the globus pallidus) or thalamotomy (i.e., surgical ablation of the thalamus). Instead, a thin lead with multiple electrodes is implanted in the globus pallidus, nucleus ventralis intermedius thalami, or subthalamic nucleus, and electric pulses are used therapeutically. The lead from the implant is extended to the neurostimulator under the skin in the chest area.

Its direct effect on the physiology of brain cells and neurotransmitters is currently debated, but by sending high-frequency electrical impulses into specific areas of the brain, it can mitigate symptoms and directly diminish the side effects induced by PD medications, allowing a decrease in medications, or making a medication regimen more tolerable.

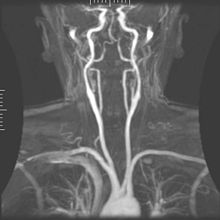

Components and placement

The DBS system consists of three components: the implanted pulse generator (IPG), the lead, and an extension. The IPG is a battery-powered neurostimulator encased in a titanium housing, which sends electrical pulses to the brain that interfere with neural activity at the target site. The lead is a coiled wire insulated in polyurethane with four platinum-iridium electrodes and is placed in one or two different nuclei of the brain. The lead is connected to the IPG by an extension, an insulated wire that runs below the skin, from the head, down the side of the neck, behind the ear, to the IPG, which is placed subcutaneously below the clavicle, or in some cases, the abdomen. The IPG can be calibrated by a neurologist, nurse, or trained technician to optimize symptom suppression and control side effects.

DBS leads are placed in the brain according to the type of symptoms to be addressed. For non-Parkinsonian essential tremor, the lead is placed in either the ventrointermediate nucleus of the thalamus or the zona incerta; for dystonia and symptoms associated with PD (rigidity, bradykinesia/akinesia, and tremor), the lead may be placed in either the globus pallidus internus or the subthalamic nucleus; for OCD and depression to the nucleus accumbens; for incessant pain to the posterior thalamic region or periaqueductal gray; and for epilepsy treatment to the anterior thalamic nucleus.

All three components are surgically implanted inside the body. Lead implantation may take place under local anesthesia or under general anesthesia ("asleep DBS"), such as for dystonia. A hole about 14 mm in diameter is drilled in the skull and the probe electrode is inserted stereotactically, using either frame-based or frameless stereotaxis. During the awake procedure with local anesthesia, feedback from the person is used to determine the optimal placement of the permanent electrode. During the asleep procedure, intraoperative MRI guidance is used for direct visualization of brain tissue and device. The installation of the IPG and extension leads occurs under general anesthesia. The right side of the brain is stimulated to address symptoms on the left side of the body and vice versa.

Research

Chronic pain

Stimulation of the periaqueductal gray and periventricular gray for nociceptive pain, and the internal capsule, ventral posterolateral nucleus, and ventral posteromedial nucleus for neuropathic pain has produced impressive results with some people, but results vary. One study of 17 people with intractable cancer pain found that 13 were virtually pain-free and only four required opioid analgesics on release from hospital after the intervention. Most ultimately did resort to opioids, usually in the last few weeks of life. DBS has also been applied for phantom limb pain.

Major depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder

DBS has been used in a small number of clinical trials to treat people with severe treatment-resistant depression (TRD). A number of neuroanatomical targets have been used for DBS for TRD including the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus,nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and the lateral habenula. A recently proposed target of DBS intervention in depression is the superolateral branch of the medial forebrain bundle; its stimulation lead to surprisingly rapid antidepressant effects.

The small numbers in the early trials of DBS for TRD currently limit the selection of an optimal neuroanatomical target. Evidence is insufficient to support DBS as a therapeutic modality for depression; however, the procedure may be an effective treatment modality in the future. In fact, beneficial results have been documented in the neurosurgical literature, including a few instances in which people who were deeply depressed were provided with portable stimulators for self-treatment.

A systematic review of DBS for TRD and OCD identified 23 cases, nine for OCD, seven for TRD, and one for both. "[A]bout half the patients did show dramatic improvement" and adverse events were "generally trivial" given the younger age of the psychiatric population relative to the age of people with movement disorders. The first randomized, controlled study of DBS for the treatment of TRD targeting the ventral capsule/ventral striatum area did not demonstrate a significant difference in response rates between the active and sham groups at the end of a 16-week study. However, a second randomized controlled study of ventral capsule DBS for TRD did demonstrate a significant difference in response rates between active DBS (44% responders) and sham DBS (0% responders). Efficacy of DBS is established for OCD, with on average 60% responders in severely ill and treatment-resistant patients. Based on these results the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved DBS for treatment-resistant OCD under a Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE), requiring that the procedure be performed only in a hospital with specialist qualifications to do so.

DBS for TRD can be as effective as antidepressants and have good response and remission rates, but adverse effects and safety must be more fully evaluated. Common side effects include "wound infection, perioperative headache, and worsening/irritable mood [and] increased suicidality".

Other clinical applications

Results of DBS in people with dystonia, where positive effects often appear gradually over a period of weeks to months, indicate a role of functional reorganization in at least some cases. The procedure has been tested for effectiveness in people with epilepsy that is resistant to medication. DBS may reduce or eliminate epileptic seizures with programmed or responsive stimulation.

DBS of the septal areas of persons with schizophrenia has resulted in enhanced alertness, cooperation, and euphoria. Persons with narcolepsy and complex-partial seizures also reported euphoria and sexual thoughts from self-elicited DBS of the septal nuclei.

Orgasmic ecstasy was reported with the electrical stimulation of the brain with depth electrodes in the left hippocampus at 3mA, and the right hippocampus at 1 mA.

In 2015, a group of Brazilian researchers led by neurosurgeon Erich Fonoff described a new technique that allows for simultaneous implants of electrodes called bilateral stereotactic procedure for DBS. The main benefits are less time spent on the procedure and greater accuracy.

In 2016, DBS was found to improve learning and memory in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. More recent (2018) work showed, that forniceal DBS upregulates genes involved in synaptic function, cell survival, and neurogenesis, making some first steps at explaining the restoration of hippocampal circuit function.

Epilepsy target

According to one long-term follow-up study, DBS targeting the anterior nucleus of the thalamus may be somewhat more effective for temporal lobe epilepsy, and efficacy may increase over time.

See also

- Brain implant

- Brain stimulation reward

- Electroconvulsive therapy

- Neuromodulation (medicine)

- Neuroprosthetics

- Responsive neurostimulation device

Further reading

- Appleby BS, Duggan PS, Regenberg A, Rabins PV (September 2007). "Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with deep brain stimulation: A meta-analysis of ten years' experience". Movement Disorders. 22 (12): 1722–1728. doi:10.1002/mds.21551. PMID 17721929. S2CID 22925963.

- Schlaepfer TE, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Hurlemann R, Coenen VA (May 2014). "Deep brain stimulation of the human reward system for major depressionsnd – rationale, outcomes and outlook". Neuropsychopharmacology. 39 (6): 1303–1314. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.28. PMC 3988559. PMID 24513970.

- Diamond A, Shahed J, Azher S, Dat-Vuong K, Jankovic J (May 2006). "Globus pallidus deep brain stimulation in dystonia". Movement Disorders. 21 (5): 692–695. doi:10.1002/mds.20767. PMID 16342255. S2CID 29677149.

- Richter, E. Oscar; Lozano, Andres M. (2004). "Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders". Bioelectromagnetic Medicine. pp. 271–282. doi:10.3109/9780203021651-24. ISBN 978-0-429-22857-5.

External links

- Video: Deep brain stimulation to treat Parkinson's disease

- Video: Deep brain stimulation therapy for Parkinson's disease

- The Perils of Deep Brain Stimulation for Depression. Author Danielle Egan. September 24, 2015.

- Treatment center for Deep Brain Stimulation of movement disorders, OCD, Tourette or depression.

- Treatment center for Deep Brain Stimulation for OCD