Kivu Ebola epidemic

Democratic Republic of the Congo & Uganda; areas affected by the epidemic.

| |||||||||||||||||

| Date | 1 August 2018 (2018-08-01) – 25 June 2020 (2020-06-25) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casualties | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Kivu Ebola epidemic was an outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) that ravaged the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in Central Africa from 2018 to 2020. Between 1 August 2018 and 25 June 2020 it resulted in 3,470 reported cases. The Kivu outbreak also affected Ituri Province, whose first case was confirmed on 13 August 2018. In November 2018, the outbreak became the biggest Ebola outbreak in the DRC's history, and had become the second-largest Ebola outbreak in recorded history worldwide, behind only the 2013–2016 Western Africa epidemic. In June 2019, the virus reached Uganda, having infected a 5-year-old Congolese boy who entered Uganda with his family, but was contained.

A military conflict in the region that had begun in January 2015 hindered treatment and prevention efforts. The World Health Organization (WHO) described the combination of military conflict and civilian distress as a potential "perfect storm" that could lead to a rapid worsening of the outbreak. In May 2019, the WHO reported that since January, 85 health workers had been wounded or killed in 42 attacks on health facilities. In some areas, aid organizations had to stop their work due to violence. Health workers also had to deal with misinformation spread by opposing politicians.

Due to the deteriorating security situation in North Kivu and surrounding areas, the WHO raised the risk assessment at the national and regional level from "high" to "very high" in September 2018. In October, the United Nations Security Council stressed that all armed hostility in the DRC should come to a stop to better fight the ongoing EVD outbreak. A confirmed case in Goma triggered the decision by the WHO to convene an emergency committee for the fourth time, and on 17 July 2019, the WHO announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the highest level of alarm the WHO can sound.

On 15 September 2019, some slowdown of EVD cases was noted by the WHO in DRC. However, contact tracing continued to be less than 100%; at the time, it was at 89%. As of mid-October the transmission of the virus had significantly reduced; by then it was confined to the Mandima region near where the outbreak began, and was only affecting 27 health zones in the DRC (down from a peak of 207). New cases dwindled to zero by 17 February 2020, but after 52 days without a case, surveillance and response teams on the ground confirmed three new cases of Ebola in Beni health zone in mid-April. On 25 June 2020, the outbreak was declared ended.

As a new and separate outbreak, the Congolese health ministry reported on 1 June 2020 that there were cases of Ebola in Équateur Province in north-western DRC, described as the eleventh Ebola outbreak since records began. This separate outbreak was declared over as of 18 November following no reported cases for 42 days, and caused 130 cases and 55 deaths.

Epidemiology

As indicated below and per numbers offered by the United Nations the final death toll was 2,280 with a total of 3,470 cases in DRC in almost a two-year period. This was made very difficult due to the ongoing military attacks in the region which created a perfect storm for the virus, despite there being a vaccine. rVSV-ZEBOV or Ebola Zaire vaccine live, is a vaccine that prevents Ebola caused by the Zaire ebolavirus. The graph of reported cases reflects cases that were not able to have a laboratory test sample before burial as probable cases.

*2018–19 Kivu Ebola epidemic (total cases-deaths as of 25 June 2020)

*xindicates (2) 21 day periods have passed and outbreak is over

Democratic Republic of the Congo

On 1 August 2018, the North Kivu health division notified Congo's health ministry of 26 cases of hemorrhagic fever, including 20 deaths. Four of the six samples that were sent for analysis to the National Institute of Biological Research in Kinshasa came back positive for Ebola and an outbreak was declared on that date. The index case is believed to have been the death and unsafe burial of a 65-year-old woman on 25 July in Mangina, quickly followed by the deaths of seven close family members. This outbreak started just days after the end of the outbreak in Équateur province. On 1 August, just after the Ebola epidemic had been declared, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) arrived in Mangina, the point of origin of the outbreak, to mount a response. On 2 August, Oxfam indicated it would be taking part in the response to this latest outbreak in the DRC. On 4 August, the WHO indicated that the current situation in the DRC, due to several factors, warranted a "high risk assessment" at the national and regional level for public health.

By 3 August, the virus had developed in multiple locations; cases were reported in five health zones – Beni, Butembo, Oicha, Musienene and Mabalako – in North Kivu province as well as Mandima and Mambasa in Ituri Province. However, one month later there had been confirmed cases only in the Mabalako, Mandima, Beni and Oicha health zones. The five suspected cases in the Mambasa Health Zone proved not to be EVD; it was not possible to confirm the one probable case in the Musienene Health Zone and the two probable cases in the Butembo Health Zone. No new cases had been recorded in any of those health zones.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu indicated on 15 August that the outbreak then in the DRC might be worse than the West African outbreak of 2013–2016, with the IRC connecting this to the ongoing Kivu conflict. The Kivu outbreak was the biggest of the ten recorded outbreaks recorded in the DRC. The first confirmed case in Butembo was announced on 4 September, the same day that it was announced that one of the cases registered at Beni had actually come from the Kalunguta Health Zone.

In November, it was reported that the EVD outbreak ran across two provinces and 14 health zones. By 23 December, the EVD outbreak had spread to more health zones, and at that time 18 such areas had been affected.

Becoming the 2nd biggest EVD outbreak

On 7 August 2018, the DRC Ministry of Public Health indicated that the total count had climbed to almost 90 cases, and the Uganda Ministry of Health issued an alert for extra surveillance as the outbreak was just 100 kilometres (62 mi) away from its border. Two days later the total count was nearly 100 cases. On 16 August, the United Kingdom indicated it would help with EVD diagnosis and monitoring in the DRC. On 17 August 2018, the WHO reported that there were around 1,500 "contacts", while noting that certain conflict zones in the DRC that could not be reached might have contained more contacts. Some 954 contacts were successfully followed up on 18 August; however, Mandima Health Zone indicated resistance, so contacts were not followed up there. On 4 September, Butembo, a city with almost one million people and an international airport, recorded its first fatality in the Ebola outbreak. The city of Butembo, in the DRC, has trade links to nearby Uganda.

On 24 September, it was reported that all contact tracing and vaccinations would stop for the foreseeable future in Beni due to a deadly attack by rebel groups the day before. On 25 September, Peter Salama of the WHO indicated that insecurity was obstructing efforts to stop the virus and believed a combination of factors could establish conditions for an epidemic. On 18 October, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) raised its travelers' alert to the DRC from a level 1 to level 2 for all U.S. travelers. On 26 October, the WHO indicated that half of confirmed cases were not showing any fever symptoms, thus making diagnosis more difficult.

According to a September 2018 Lancet survey, 25% of respondents in Beni and Butembo believed the Ebola outbreak to be a hoax. These beliefs correlated with decreased likelihood of seeking healthcare or accepting vaccination.

On 6 November 2018, the CDC indicated that the current outbreak in the east region of the DRC was potentially non-containable. This would be the first time since 1976 that an outbreak was not able to be curbed. On 13 November, the WHO indicated that the viral outbreak would last at least six months.

On 29 December 2018, the DRC Ministry of Public Health announced that there had been "0 new confirmed cases detected because of the paralysis of the activities of the response in Beni, Butembo, Komanda and Mabalako" and no vaccination had occurred for three consecutive days. On 22 January, the total case count approached 1,000 cases, (951 suspected) in the DRC Ministry of Public Health situation report. The graphs below demonstrate the EVD intensity in different locations in the DRC, as well as in the West African epidemic of 2014–15 as a comparison:

On 16 March 2019, the director of the CDC indicated that the outbreak in the DRC could last another year, additionally suggesting that vaccine supplies could run out. According to the WHO, resistance to vaccination in the Kaniyi Health Zone was ongoing as of March 2019. There was still a belief by some in surrounding areas that the epidemic was a hoax.

Until the outbreak in North Kivu in 2018, no outbreak had surpassed 320 total cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By 24 February 2019, the epidemic had surpassed 1,000 total cases (1,048).

On 10 May 2019, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that the outbreak could eventually surpass the West African epidemic.

The 12 May 2019 issue of WHO Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, indicates that "continued increase in the number of new EVD cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is worrying...no end in sight to the difficult security situation". On 25 November 2019, it was reported that violence had broken out in Beni again, to such a degree that some aid agencies had evacuated. According to the same report, around 300 individuals might have been exposed to EVD via an infected individual.

Spread to Goma

On 14 July 2019, the first case of EVD was confirmed in the capital of North Kivu, Goma, a city with an international airport and a highly mobile population of 2 million people located near the DRC's eastern border with Rwanda. This case was a man who had passed through three health checkpoints, with different names on traveller lists. The WHO stated that he died in a treatment centre, whereas according to Reuters he died en route to a treatment centre. This case triggered the decision by the WHO to again reconvene an emergency committee, where the situation was officially declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

On 30 July, a second case of EVD was confirmed in the city of Goma, apparently not linked to the first case. Across the border from Goma in the country of Rwanda, Ebola simulation drills were being conducted at health facilities. A third case of EVD was confirmed in Goma on 1 August. On 22 August 2019, Nyiragongo Health Zone, the affected area on the outskirts of Goma, reached 21 days without further cases being confirmed.

Spread to South Kivu Province

On 16 August 2019, it was reported that the Ebola virus disease had spread to a third province – South Kivu – via two new cases who had travelled from Beni, North Kivu. By 22 August the number of cases in Mwenga had risen to four, including one person at a health facility visited by the first case.

Uganda

In August 2018 a UN agency indicated that active screening was deployed to ensure that those leaving the DRC into Uganda were not infected with Ebola. The government of Uganda opened two Ebola treatment centers at the border with the DRC, though there had not yet been any confirmed cases in the country of Uganda. By 13 June 2019, nine treatment units were in place near the affected border.

According to the International Red Cross, a "most likely scenario" entailed an asymptomatic case entering the country of Uganda undetected among the numerous refugees then coming from the DRC. On 20 September, Uganda indicated it was ready for immediate vaccination, should the Ebola virus be detected in any individual.

On 21 September, officials of the DRC indicated a confirmed case of EVD at Lake Albert, an entry point into Uganda, though no cases were then confirmed within Ugandan territory.

On 2 November, it was reported that the Ugandan government would start vaccinating health workers along the border with the DRC as a proactive measure against the virus. Vaccinations started on 7 November, and by 13 June 2019, 4,699 health workers at 165 sites had been vaccinated. Proactive vaccination was also carried out in South Sudan, with 1,471 health workers vaccinated by 7 May 2019.

On 2 January 2019, it was reported that refugee movement from the DRC to Uganda had increased after the presidential elections. On 12 February, it was reported that 13 individuals had been isolated due to their contact with a suspected Ebola case in Uganda; lab results came back negative several hours later.

On 11 June 2019, the WHO reported that the virus had spread to Uganda. A 5-year-old Congolese boy entered Uganda on the previous Sunday with his family to seek medical care. On 12 June, the WHO reported that the 5-year-old patient had died, while 2 more cases of Ebola infection within the same family were also confirmed. On 14 June it was reported that there were 112 contacts since EVD was first detected in Uganda.Ring vaccination of Ugandan contacts was scheduled to start on 15 June. As of 18 June 2019, 275 contacts had been vaccinated per the Uganda Ministry of Health.

On 14 July, an individual entered the country of Uganda from DRC while symptomatic for EVD; a search for contacts in Mpondwe followed. On 24 July, Uganda marked the needed 42 day period without any EVD cases to be declared Ebola-free. On 29 August, a 9-year-old Congolese girl became the fourth individual in Uganda to test positive for EVD when she crossed from the DRC into the district of Kasese.

Tanzania

In regards to possible EVD cases in Tanzania, the WHO stated on 21 September 2019 that "to date, the clinical details and the results of the investigation, including laboratory tests performed for differential diagnosis of these patients, have not been shared with WHO. The insufficient information received by WHO does not allow for a formulation of a hypotheses regarding the possible cause of the illness". On 27 September, the CDC and U.S. State Department alerted potential travellers to the possibility of unreported EVD cases within Tanzania.

The Tanzanian Health Minister Ummy Mwalimu stated on 3 October 2019 that there was no Ebola outbreak in Tanzania. The WHO were provided with a preparedness update on 18 October which outlined a range of actions, and included commentary that since the outbreak commenced, there had been "29 alerts of Ebola suspect cases reported, 17 samples tested and were negative for Ebola (including 2 in September 2019)".

Countries with medically evacuated individuals

On 29 December, an American physician who was exposed to the Ebola virus (and who was non-symptomatic) was evacuated, and taken to the University of Nebraska Medical Center. On 12 January, the individual was released after 21 days without symptoms.

The table which follows indicates confirmed, probable and suspected cases, as well as deaths; the table also indicates the multiple countries where these cases took place, during this outbreak.

| Date | Cases # | Deaths | CFR | Contacts | Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | Probable | Suspected | Totals | |||||

| DRC.2018-08-01†DRC | 4 | 22 | 0 | 26 | 20 | - | - | |

| 2018-08-03 | 13 | 30 | 33 | 76 | 33 | 0.76.7%‡ | 879 | |

| 2018-08-05 | 16 | 27 | 31 | 74 | 34 | 79%‡ | 966 | |

| 2018-08-10 | 25 | 27 | 48 | 100 | 39 | 75%‡ | 953 | |

| 2018-08-12 | 30 | 27 | 58 | 115 | 41 | - | 997 | |

| 2018-08-17 | 64 | 27 | 12 | 103 | 50 | 0.55.6%‡ | 1,609 | |

| 2018-08-20 | 75 | 27 | 9 | 111 | 59 | - | 2,408 | |

| 2018-08-24 | 83 | 28 | 6 | 117 | 72 | 65%‡ | 3,421 | |

| 2018-08-26 | 83 | 28 | 10 | 121 | 75 | 0.67.6%‡ | 2,445 | |

| 2018-08-31 | 90 | 30 | 8 | 128 | 78 | 65%‡ | 2,462 | |

| 2018-09-02 | 91 | 31 | 9 | 131 | 82 | - | 2,512 | |

| 2018-09-07 | 100 | 31 | 14 | 145 | 89 | 68%‡ | 2,426 | |

| 2018-09-09 | 101 | 31 | 9 | 141 | 91 | - | 2,265 | |

| 2018-09-14 | 106 | 31 | 17 | 154 | 92 | 0.67.2%‡ | 1,751 | |

| 2018-09-16 | 111 | 31 | 7 | 149 | 97 | - | 2,173 | |

| 2018-09-21 | 116 | 31 | n/a | 147 | 99 | 0.67.3%‡ | 1,641 | |

| 2018-09-23 | 119 | 31 | 9 | 159 | 100 | 67%‡ | 1,836 | |

| 2018-09-28 | 126 | 31 | 23 | 180 | 102 | 65%‡ | 1,410 | |

| 2018-10-02 | 130 | 32 | 17 | 179 | 106 | 0.65.4%‡ | 1,463 | |

| 2018-10-05 | 142 | 35 | 11 | 188 | 113 | 0.63.8%‡ | 2,045 | |

| 2018-10-07 | 146 | 35 | 21 | 202 | 115 | 0.63.5%‡ | 2,115 | |

| 2018-10-12 | 176 | 35 | 32 | 243 | 135 | 64%‡ | 2,663 | |

| 2018-10-15 | 181 | 35 | 32 | 248 | 139 | 64%‡ | 4,707 | |

| 2018-10-19 | 202 | 35 | 33 | 270 | 153 | 65%‡ | 5,518 | |

| 2018-10-21 | 203 | 35 | 14 | 252 | 155 | 65%‡ | 5,341 | |

| 2018-10-26 | 232 | 35 | 43 | 310 | 170 | 64%‡ | 6,026 | |

| 2018-10-28 | 239 | 35 | 32 | 306 | 174 | 0.63.5%‡ | 5,991 | |

| 2018-11-02 | 263 | 35 | 70 | 368 | 186 | 0.62.4%‡ | 5,036 | |

| 2018-11-04 | 265 | 35 | 61 | 361 | 186 | 62%‡ | 4,971 | |

| 2018-11-09 | 294 | 35 | 60 | 389 | 205 | 62%‡ | 4,779 | |

| 2018-11-11 | 295 | 38 | n/a | 333 | 209 | - | 4,803 | |

| 2018-11-16 | 319 | 47 | 49 | 415 | 214 | 59%‡ | 4,430 | |

| 2018-11-21 | 326 | 47 | 90 | 463 | 217 | - | 4,668 | |

| 2018-11-23 | 365 | 47 | 45 | 457 | 236 | 57%‡ | 4,354 | |

| 2018-11-26 | 374 | 47 | 74 | 495 | 241 | 57%‡ | 4,767 | |

| 2018-11-30 | 392 | 48 | 63 | 503 | 255 | 58%‡ | 4,820 | |

| 2018-12-03 | 405 | 48 | 79 | 532 | 268 | 59%‡ | 5,335 | |

| 2018-12-07 | 446 | 48 | 95 | 589 | 283 | 57%‡ | 6,417 | |

| 2018-12-10 | 452 | 48 | n/a | 500 | 289 | 58%‡ | 6,509 | |

| 2018-12-14 | 483 | 48 | 111 | 642 | 313 | 59%‡ | 6,695 | |

| 2018-12-21 | 526 | 48 | 118 | 692 | 347 | 60%‡ | 8,422 | |

| 2018-12-28 | 548 | 48 | 52 | 648 | 361 | 61%‡ | 7,007 | |

| 2019-01-04 | 575 | 48 | 118 | 741 | 374 | 60%‡ | 5,047 | |

| 2019-01-11 | 595 | 49 | n/a | 644 | 390 | 61%‡ | 4,937 | |

| 2019-01-18 | 636 | 49 | 209 | 894 | 416 | 61%‡ | 4,971 | |

| 2019-01-25 | 679 | 54 | 204 | 937 | 459 | 63%‡ | 6,241 | |

| 2019-02-01 | 720 | 54 | 168 | 942 | 481 | 62%‡ | >7,000 | |

| 2019-02-10 | 750 | 61 | 148 | 959 | 510 | 63%‡ | 7,846 | |

| 2019-02-18 | 773 | 65 | 135 | 973 | 534 | 64%‡ | 6,772 | |

| 2019-02-24 | 804 | 65 | 219 | 1,088 | 546 | 63%‡ | 5,739 | |

| 2019-03-03 | 830 | 65 | 182 | 1,077 | 561 | 63%‡ | 5,613 | |

| 2019-03-10 | 856 | 65 | 191 | 1,112 | 582 | 63%‡ | 4,830 | |

| 2019-03-17 | 886 | 65 | 231 | 1,182 | 598 | 63%‡ | 4,158 | |

| 2019-03-25 | 944 | 65 | 226 | 1,235 | 629 | 62%‡ | 4,132 | |

| 2019-03-31 | 1,016 | 66 | 279 | 1,361 | 676 | 62%‡ | 6,989 | |

| 2019-04-07 | 1,080 | 66 | 282 | 1,428 | 721 | 63%‡ | 7,099 | |

| 2019-04-14 | 1,185 | 66 | 269 | 1,520 | 803 | 64%‡ | 10,461 | |

| 2019-04-21 | 1,270 | 66 | 92 | 1,428 | 870 | 65%‡ | 5,183 | |

| 2019-04-28 | 1,373 | 66 | 176 | 1,615 | 930 | 65%‡ | 11,841 | |

| 2019-05-05 | 1,488 | 66 | 205 | 1,759 | 1,028 | 66%‡ | 12,969 | |

| 2019-05-12 | 1,592 | 88 | 534 | 2,214 | 1,117 | 67%‡ | 13,174 | |

| 2019-05-19 | 1,728 | 88 | 278 | 2,094 | 1,209 | 67%‡ | 12,608 | |

| 2019-05-26 | 1,818 | 94 | 277 | 2,189 | 1,277 | 67%‡ | 20,415 | |

| 2019-06-02 | 1,900 | 94 | 316 | 2,310 | 1,339 | 67%‡ | 19,465 | |

| 2019-06-09 | 1,962 | 94 | 271 | 2,327 | 1,384 | 67%‡ | 15,045 | |

| 2019-06-16 DRC & Uganda |

2,051 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 319 / 1 | 2,468 | 1,440 | 67%‡/100%‡ | 15,992 / 90 | |

| 2019-06-23 | 2,145 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 276 / 0 | 2,515 | 1,506 | 67%‡/100%‡ | 15,903 / 110 | |

| 2019-06-30 | 2,231 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 309 / 0 | 2,634 | 1,563 | 67%‡/100%‡ | 18,088 / 108 | |

| 2019-07-07 | 2,314 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 323 / 0 | 2,731 | 1,625 | 68%‡/100%‡ | 19,227 / 0 | |

| 2019-07-14 | 2,407 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 335 / 0 | 2,836 | 1,665 | 67%‡/100%‡ | 19,118 / 0 | |

| 2019-07-21 | 2,484 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 361 / 0 | 2,939 | 1,737 | 67%‡/100%‡ | 20,505 / 19 | |

| DRC.2019-07-28 DRC | 2,565 | 94 | 358 | 3,017 | 1,782 | 67%‡ | 20,072 | |

| 2019-08-04 | 2,659 | 94 | 397 | 3,150 | 1,843 | 67%‡ | 19,156 | |

| 2019-08-11 | 2,722 | 94 | 326 | 3,142 | 1,888 | 67%‡ | 15,988 | |

| 2019-08-19 | 2,783 | 94 | 387 | 3,264 | 1,934 | 67%‡ | 15,817 | |

| 2019-08-25 | 2,863 | 105 | 396 | 3,364 | 1,986 | 67%‡ | 17,293 | |

| 2019-09-01 | 2,926 | 105 | 365 | 3,396 | 2,031 | 67%‡ | 16,370 | |

| 2019-09-08 | 2,968 | 111 | 403 | 3,486 | 2,064 | 67%‡ | 14,737 | |

| 2019-09-15 | 3,005 | 111 | 497 | 3,613 | 2,090 | 67%‡ | 13,294 | |

| 2019-09-22 | 3,053 | 111 | 415 | 3,583 | 2,115 | 67%‡ | 11,335 | |

| 2019-09-29 | 3,074 | 114 | 426 | 3,618 | 2,133 | 67%‡ | 7,775 | |

| 2019-10-06 | 3,090 | 114 | 414 | 3,622 | 2,146 | 67%‡ | 7,807 | |

| 2019-10-13 | 3,104 | 114 | 429 | 3,647 | 2,150 | 67%‡ | 5,622 | |

| 2019-10-20 | 3,123 | 116 | 420 | 3,659 | 2,169 | 67%‡ | 5,570 | |

| 2019-10-28 | 3,146 | 117 | 357 | 3,624 | 2,180 | 67%‡ | 4,437 | |

| 2019-11-03 | 3,157 | 117 | 513 | 3,787 | 2,185 | 67%‡ | 6,078 | |

| 2019-11-10 | 3,169 | 118 | 482 | 3,769 | 2,193 | 67%‡ | 6,137 | |

| 2019-11-17 | 3,174 | 118 | 422 | 3,714 | 2,195 | 67%‡ | 4,857 | |

| 2019-11-24 | 3,183 | 118 | 349 | 3,650 | 2,198 | 67%‡ | 3,371 | |

| 2019-12-08 | 3,202 | 118 | 391 | 3,711 | 2,209 | 67%‡ | 2,955 | |

| 2019-12-22 | 3,240 | 118 | 446 | 3,804 | 2,224 | 66%‡ | 5,137 | |

| 2020-01-05 | 3,270 | 118 | 464 | 3,852 | 2,233 | 66%‡ | 4,133 | |

| 2020-01-19 | 3,293 | 119 | 438 | 3,854 | 2,241 | 66%‡ | 5,018 | |

| 2020-02-02 | 3,305 | 123 | 447 | 3,879 | 2,250 | 66%‡ | 2,374 | |

| 2020-02-16 | 3,309 | 123 | 504 | 3,936 | 2,253 | 66%‡ | 1,972 | |

| 2020-03-29 | 3,310 | 143 | 232 | 3,685 | 2,273 | 66%‡ | - | |

| 02020-06-25x | 3,313 | 153 | 0 | 3,470 | 2,280 | 66%‡ | - | |

|

#These figures may increase when new cases are discovered, and fall consequently, when tests show cases were not Ebola-related. | ||||||||

Outbreak and military conflict

At the time of the epidemic, there were about 70 armed military groups, among them the Alliance of Patriots for a Free and Sovereign Congo and the Mai-Mayi Nduma défense du Congo-Rénové, in North Kivu. The fighting displaced thousands of individuals and seriously affected the response to the outbreak. According to the WHO, health care workers were to be accompanied by military personnel for protection and ring vaccination may not be possible. On 11 August 2018, it was reported that seven individuals were killed in Mayi-Moya due to a militant group, about 24 miles from the city of Beni where there were several EVD cases.

On 24 August 2018, it was reported that an Ebola-stricken physician had been in contact with 97 individuals in an inaccessible military area, who hence could not be diagnosed. In September, it was reported that 2 peacekeepers were attacked and wounded by rebel groups in Beni, and 14 individuals were killed in a military attack. In September 2018, the WHO's Deputy Director-General for Emergency Preparedness and Response described the combination of military conflict and civilian distress as a potential "perfect storm" that could lead to a rapid worsening of the outbreak.

On 20 October 2018, an armed rebel group in the DRC killed 13 civilians and took 12 children as hostages in Beni, which was then experiencing one of the worst outbreaks. On 11 November, six people were killed in an attack by an armed rebel group in Beni; as a consequence vaccinations were suspended there. Yet another attack reported on 17 November, in Beni by an armed rebel group forced the cessation of EVD containment efforts and WHO staff to evacuate to another DRC city for the time being. Beni continued to be the site of attacks by militant groups as 18 civilians were killed on 6 December. On 22 December, it was reported that elections for the President of the DRC would go forward despite the EVD outbreak, including in the Ebola-stricken area of Beni. Four days later, on 26 December, the DRC government reversed itself to indicate those Ebola-stricken areas, such as Beni, would not vote for several months; as a consequence election protesters ransacked an Ebola assessment center in Beni. Post election tensions continued when it was reported that the DRC government had cut off internet connectivity for the population, as the vote results were yet to be released.

On 29 December 2018, Oxfam said it would suspend its work due to the ongoing violence in the DRC; on the same day, the International Rescue Committee suspended their Ebola support efforts as well. On 18 January, the African Union indicated that presidential election results announcements should be suspended in the DRC.

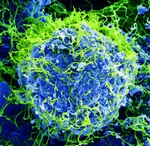

Pathogen

The DRC Ministry of Public Health confirmed that the new Ebola outbreak was caused by the Zaire ebolavirus species – the same strain involved in the early 2018 outbreak in western DRC, but different genetic coding. The most lethal of the six known strains (including the newly discovered Bombali strain),Zaire ebolavirus strain is fatal in up to 90% of cases. Both Ebola and Marburg virus are part of the Filoviridae family, which is a virus family that causes severe hemorrhagic fever.

The natural reservoir of the virus is thought to be the African fruit bat, which is used in many parts of Africa as bushmeat.

Viral mechanism

A significant part of the actual EVD infection is based on immune suppression along with systemic inflammation, leading to multiple organ failure and shock. Systemic inflammation and fever may damage many types of tissues in the body but the consequences are especially profound in the liver where Ebola wipes out cells required to produce coagulation. In the gastrointestinal tract damaged cells lead to diarrhea putting patients at risk of dehydration. And in the adrenal gland the virus cripples the cells that make steroids which regulate blood pressure, resulting in circulatory collapse.

Genetic epidemiology

Genetic epidemiology is a medical field that studies how genetic factors and the environment interact, in this case the outbreak affecting the populations of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the neighboring country of Uganda. Genetic sequencing had already identified another unrelated strain of Zaire ebolavirus that was implicated in the 2018 outbreak in Équateur province which had ended only a week previously. This was the first time two epidemiologically and genetically distinct outbreaks of Ebola had emerged within weeks of each other. In 2020 a third outbreak of Zaire ebolavirus occurred in the DRC. Genome sequencing suggests that this outbreak – the 11th outbreak since the virus was first discovered in the country in 1976 – is related to neither the one in North Kivu Province nor the previous outbreak in the same area in 2018.

Transmission

Ebola virus is found in a variety of bodily fluids, such as breast milk, saliva, stool, blood, and semen, rendering it highly contagious due to ease of contact. Although a few transmission methods are known, there is a possibility that many other methods are unknown and must be further researched. Here are some potential routes of transmission:

- Droplets: Droplet transmission occurs when contact is made with virus-containing droplets.

- Fomites: Occurs when an individual comes in contact with a pathogen-containing surface.

- Bodily fluids: The most common way of transmitting the Ebola virus in humans is through contact with infected bodily fluids.

Those infected by EVD generally gain immunity, although it is considered possible that such immunity is only temporary. On 31 October 2019, it was reported that an EVD survivor who had been assisting at a treatment center in Beni had been reinfected with EVD and died; such an incident was unprecedented.

Containment and control

Even with the advances made in vaccine technology and treatment options during previous Ebola outbreaks, effective control of the North Kivu Epidemic continued to rely on traditional public health efforts including the timely identification and isolation of cases, control measures in hospital settings, identification and follow-up of contacts, community engagement, and safe burials. Data from the West African Ebola Outbreak showed that response strategies that achieved 60% efficacy for sanitary burial, case isolation, and contact-tracing combined, could have greatly reduced the daily number of Ebola cases and ended the outbreak after only 6 months.

Surveillance and contact tracing

Contact tracing is defined as the identification and follow-up of persons who may have been in contact with a person infected with Ebola. Ideally, close contacts are observed for 21 days after their last known exposure to a case and isolated if they become symptomatic. The volume of contacts and the duration of monitoring presented challenges in Ebola surveillance as it required careful record-keeping by properly trained and equipped staff. To strengthen surveillance activities, the DRC Ministry of Health began disseminating standardized Ebola case definitions, developed reporting tools, and communication strategies, and began distribution of daily situation reports. Rapid response teams were deployed to affected health zones to strengthen Ebola case management and infection prevention and control in health care facilities and treatment centers. Similar to the West African Ebola Outbreak, relatively few (less than 10%) Ebola cases presented with hemorrhagic symptoms.

In North Kivu and Ituri, outbreaks of sporadic violence and suspicion of the response in parts of some affected communities impacted heavily on disease surveillance. Poor record keeping by local health facilities also made it difficult or impossible to identify and trace contacts that might have been exposed to the disease while they were undergoing treatment for other illness at health centers. Additionally, the high degree of mobility of affected populations, combined with occasional mistrust of the response has meant that contacts that had been identified have sometimes been lost to follow-up for extended periods. Initially, it was estimated that 30-50% of contacts may not have originally been registered by contact tracing teams.

Community engagement and awareness

Surveys among the affected population in North Kivu and Ituri showed both general mistrust with the Ebola response, partly related to years of mistrust of any governmental or external action, and specific opposition to the response because of conflicts with local cultural practices. Some of the cultural practices which complicated the Ebola response included eating bush meat, regular gatherings at family or village events, and traditional funeral practices, which were events that were particularly high risk for Ebola transmission. Additionally, people from the affected region reported that their perception of security and trust in the government, as well as humanitarian workers, declined over the course of the outbreak, complicating an already complex response.

Misinformation

Combatting misinformation was a key element in overcoming Ebola in North Kivu. One study using surveys found that low institutional trust coupled with a belief in misinformation about Ebola were inversely associated with preventive behaviors in individuals, including Ebola vaccine acceptance. Belief in misinformation regarding Ebola was widespread, with 25% of respondents reporting that they did not believe the Ebola outbreak was real. Some of the rumors that were being circulated included statements that the outbreak did not exist, it was fabricated by the authorities for financial gains, or was fabricated to destabilize the region. Approximately 68% of respondents reported that they did not trust the local authorities to represent their interest, and community trust in the Ebola response was often further undermined by misinformation spread by local politicians.

Delay in seeking treatment

Early in the epidemic there were delays in patients seeking care for Ebola because the initial cases were misdiagnosed. Ebola symptoms were similar to symptoms of more common infectious diseases such as malaria, flu, and typhoid fever so patients would wait until their clinical situation deteriorated dangerously, usually after failure to respond to anti-malarial and/or antibiotic regimens, before reporting to the hospitals.

Burials

The IFRC has called funerals "super-spreading events" as burial traditions include kissing and generally touching bodies. Safe burial teams formed by health workers are subject to suspicion.

Travel restrictions and border closings

On 26 July 2019, it was reported that the country of Saudi Arabia would not allow visas from the DRC after the WHO declared it an international emergency due to EVD. On 1 August 2019, the country of Rwanda closed its border with the DRC after multiple cases in the city of Goma, which borders the country in the upper Northwestern region.

To minimize the risk of the spread to neighboring countries, screening points which consisted of temperature and symptom monitoring were established at many border crossings. Over 2 million screenings were undertaken during the outbreak which no doubt contributed to the containment of the epidemic within DRC.

Treatment

In August 2018, the WHO evaluated several drugs used to treat EVD, including Remdesivir, ZMapp, atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, ansuvimab and favipiravir. The drug ansuvimab (which is a monoclonal antibody) was deployed for the first time to treat infected individuals during this EVD outbreak.

In November 2018, the DRC gave approval to start randomized clinical trials for EVD treatment. On 12 August 2019, it was announced that two clinical trial medications were found to improve the rate of survival in those infected by EVD: atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, a cocktail of three monoclonal Ebola antibodies, and ansuvimab. These two will be further used in therapy; when used shortly after infection they were found to have a 90% survival rate. ZMapp and Remdesivir were subsequently discontinued.

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab with an indication for the treatment of infection caused by Zaire ebolavirus.

Vaccination

On 8 August 2018, the process of vaccination began with rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine. While several studies have shown the vaccine to be safe and protective against the virus, additional research is needed before it can be licensed. Consequently, the WHO reported that it was being used under a ring vaccination strategy with what is known as "compassionate use" to protect persons at highest risk of the Ebola outbreak, i.e. contacts of those infected, contacts of those contacts, and front-line medical personnel. As of 15 September, according to the WHO, almost a quarter of a million individuals had been vaccinated in the outbreak.

On 20 September 2019 it was reported that a second vaccine by Johnson & Johnson would be introduced in the current EVD epidemic in the DRC.

In November 2019, the World Health Organization prequalified an Ebola vaccine, rVSV-ZEBOV, for the first time. As of 22 February 2020, a total of 297,275 people had been vaccinated since the start of the outbreak. By 21 June 2020, 303,905 people had been vaccinated with rVSV-ZEBOV and 20,339 were given the initial dose of Ad26-ZEBOV/MVA-BN-FILO.

Vaccination has helped to contain the epidemic, though military attacks and community resistance have complicated distribution of the vaccines.

Pregnant and lactating women

Based on a lack of evidence about the safety of the vaccine during pregnancy, the DRC ministry of health and the WHO decided to cease vaccinating women who were pregnant or lactating. Some authorities criticized this decision as ethically "utterly indefensible". They noted that as caregivers of the sick, pregnant and lactating women are more likely to contract Ebola. They also noted that since it is known that almost 100% of pregnant women who contract Ebola will die, a safety concern should not be a deciding factor. As of June 2019, pregnant and lactating women were also being vaccinated.

Vaccine stockpile

The DRC Ministry of Public Health reported on 16 August 2018 that 316 individuals had been vaccinated. On 24 August, the DRC indicated it had vaccinated 2,957 individuals, including 1,422 in Mabalako against the Ebola virus. By late October, more than 20,000 individuals had been vaccinated. In December, Dr. Peter Salama, who is Deputy Director-General of Emergency Preparedness and Response for WHO, reported that the current 300,000 vaccine stockpile might not be enough to contain the EVD outbreak, especially since it takes several months to make more of the Zaire EVD vaccine (rVSV-ZEBOV). On 11 December, it was reported that Beni only had 4,290 doses of vaccine in stock.

As of August 2019, Merck & Co, the producers of the vaccine in use, reported a stockpile sufficient for 500,000 individuals, with more in production.

Effectiveness

In April 2019, the WHO published the preliminary results of its research, in association with the DRC's Institut National pour la Recherche Biomedicale, into the effectiveness of the ring vaccination program, including data from 93,965 at-risk people who had been vaccinated. WHO stated that the rVSV-ZEBOV-GP vaccine had been 97.5% effective at stopping Ebola transmission. The vaccine had also reduced mortality among those who were infected after vaccination. The ring vaccination strategy was effective at reducing EVD in contacts of contacts (tertiary cases), with only two such cases being reported.

Treatment centres

In August 2018, the Mangina Ebola Treatment Center was reported to be operational. A fourth Ebola Treatment Center (after those in Mangina, Beni and Butembo) was inaugurated in September in Makeke in the Mandima Health Zone of Ituri Province. Makeke is less than five kilometers from Mangina along a well-traveled local road; the site had been proposed in August when it appeared that a second Ebola Treatment Center would be needed in the area, and space was insufficient in Mangina itself to accommodate one. By mid-September, however, there had been only two additional cases in the Mandima Health Zone, and only sporadic cases were being reported in the Mabalako Health Zone.

In February 2019, it was reported that attacks at treatment centers had been carried out in Butembo and Katwa. The motives behind the attacks were unclear. Due to the violence, international aid organizations had to stop their work in the two communities. In April, an epidemiologist from WHO was killed and two health workers injured in a militia attack on Butembo University Hospital in Katwa. In May, WHO's health emergencies chief said insecurity had become a "major impediment" to controlling the outbreak. He reported that since January there had been 42 attacks on health facilities and 85 health workers had been wounded or killed. "Every time we have managed to regain control over the virus and contain its spread, we have suffered major, major security events. We are anticipating a scenario of continued intense transmission".

Healthcare workers

Health workers must wear personal protection equipment during treatment of those affected by the virus. On 3 September 2018, WHO stated that 16 health workers had contracted the virus. On 10 December, the WHO reported that the current DRC outbreak had led to 49 healthcare workers contracting the Ebola virus, and 15 had died. As of 30 April 2019, there have been 92 health care workers in the DRC infected with EVD, of which 33 had died. With false rumors being spread by word-of-mouth and social media, residents remain mistrustful and fearful of health care workers. In January 2020, it was reported that there had been nearly 400 attacks on medical workers since the outbreak began in 2018.

Post-Ebola virus syndrome

In terms of prognosis, aside from the possible effects of post-Ebola syndrome, there is also the reality of survivors returning to communities where they might be shunned due to the fear many have towards the Ebola virus, hence psychosocial assistance is needed. Many survivors of EVD face serious side effects, including but not limited to the following:

History

The Ebola virus disease outbreak in Zaire (Yambuku) started in late 1976, and was the second outbreak ever after the earlier one in Sudan the same year. On 1 August 2018, the tenth Ebola outbreak was declared in the DRC, only a few days after a prior outbreak in the same country had been declared over on 24 July.

- Table 2.

| Date | Country | Major location | Outbreak information | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Cases | Deaths | CFR | ||||

| Aug 1976 | Zaire | Yambuku | EBOV | 318 | 280 | 88% | |

| Jun 1977 | Zaire | Tandala | EBOV | 1 | 1 | 100% | |

| May–Jul 1995 | Zaire | Kikwit | EBOV | 315 | 254 | 81% | |

| Aug–Nov 2007 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 264 | 187 | 71% | |

| Dec 2008–Feb 2009 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 32 | 14 | 45% | |

| Jun–Nov 2012 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Orientale | BDBV | 77 | 36 | 47% | |

| Aug–Nov 2014 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Tshuapa | EBOV | 66 | 49 | 74% | |

| May–Jul 2017 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Likati | EBOV | 8 | 4 | 50% | |

| Apr–Jul 2018 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | EBOV | 54 | 33 | 61% | |

| Aug 2018–June 2020 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kivu | EBOV | 3,470 | 2,280 | 66% | |

| June–Nov 2020 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | EBOV | 130 | 55 | 42% | |

| Feb 2021–May 2021 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | North Kivu | EBOV | 12 | 6 | 50% | |

| April 2022 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | EBOV | 5 | 5 | 100% | |

| August 2022 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | North Kivu | EBOV | 1 | 1 | 100% | |

Learning from other responses, such as in the 2000 outbreak in Uganda, the WHO established its Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, and other public health measures were instituted in areas at high risk. Field laboratories were established to confirm cases, instead of shipping samples to South Africa. Additionally, the outbreak was closely monitored by the CDC Special Pathogens Branch.

Statistical measures

One way to measure the outbreak is via the basic reproduction number, R0, a statistical measure of the average number of people expected to be infected by one person with a disease. If the basic reproduction number is less than 1, the infection dies out; if it is greater than 1, the infection continues to spread—with exponential growth in the number of cases. A March 2019 paper by Tariq et al. suggested that R0 was oscillating around 0.9.

Response

During the Ebola outbreak in Democratic Republic of the Congo, a number of organizations helped in different capacities: CARITAS DRC, CARE International, Cooperazione Internationale (COOPE), Catholic Organization for Relief and Development Aid (CORDAID/PAP-DRC), International Rescue Committee (IRC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Oxfam, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and Samaritan's Purse.

WHO

On 12 April 2019, the WHO Emergency Committee was reconvened by the WHO Director-General after an increase in the rate of new cases, and determined that the outbreak still failed to meet the criteria for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).

Following the confirmation of Ebola crossing into Uganda, a third review by the WHO on 14 June 2019 concluded that while the outbreak was a health emergency in the DRC and the region, it did not meet all three criteria required for a PHEIC. Following a case in Goma, the reconvening of a fourth review was announced on 15 July 2019. The WHO officially declared the situation a PHEIC on 17 July 2019, and as of 12 February 2020, it continues to be a PHEIC.

Sex abuse accusations

In September 2021, a commission found that between 2018 and 2020, WHO staff had engaged in sex abuse and rape. The report prompted WHO's chief Tedros Adhanom to issue a formal apology to those women and girls affected.

World Bank

The World Bank was criticised when its Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility, intended to support countries affected by pandemic diseases, had only paid out $31 million of a potential total of $425 million by August 2019 while generating substantial returns for investors. The conditions used to decide when the fund should pay out to disease-affected countries were criticised as too stringent.

International governments

Financial support has been contributed by the governments of the US and the UK, among others. The UK DfID minister, Rory Stewart, visited the area in July 2019, and called for other western countries, including Canada, France and Germany, to donate more financial aid. He identified a funding deficit of $100–300 million to continue responding to the outbreak until December. He urged WHO to classify the situation as a PHEIC, to facilitate the release of international aid.

Subsequent outbreaks and other regional health issues

2020 Équateur province

On 1 June 2020, the Congolese health ministry announced a new DRC outbreak of Ebola in Mbandaka, Équateur Province, a region along the Congo River. This area was the site of the 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak, which infected 53 people and resulted in 29 deaths. That outbreak was quickly brought under control with the use of the Ebola vaccine.

Genome sequencing suggested that this 2020 outbreak, the 11th outbreak since the virus was first discovered in the country in 1976, was unrelated to the one in North Kivu Province or the previous outbreak in the same area in 2018. It was reported that six cases had been identified with four fatalities. It was expected that more people would be identified as surveillance activities increased.

The WHO assisted with the response to this outbreak in part using the structures put in place for the 2018 outbreak. Testing and contact tracing was used and additional medical staff had been sent in.Médecins Sans Frontières was also on hand to give assistance if needed. The outbreak added to an already difficult time for the Congo due to both COVID-19 cases and a large measles outbreak that has caused more than 7,000 deaths as of August 2020.

By 8 June, a total of 12 cases had been identified in and around Mbandaka and 6 deaths due to the virus. The WHO said 300 people in Mbandaka and the surrounding Équateur province had been vaccinated. By 15 June the case count had increased to 17 with 11 deaths, with more than 2,500 people having been vaccinated. On 17 October, it had increased to 128 cases and 53 deaths, despite an effective vaccine being available. As of 18 November, the World Health Organization has had no reported cases of Ebola in Équateur province for 42 days; therefore the outbreak is over. In the end there were 130 cases and 55 dead due to the virus.

![]() This article was submitted to WikiJournal of Medicine for external academic peer review in 2021 (reviewer reports). The updated content was reintegrated into the Wikipedia page under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license (2022). The version of record as reviewed is:

Osmin Anis; et al. (13 April 2022). "The Kivu Ebola epidemic" (PDF). WikiJournal of Medicine. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.15347/WJM/2022.001. ISSN 2002-4436. Wikidata Q105411509.

This article was submitted to WikiJournal of Medicine for external academic peer review in 2021 (reviewer reports). The updated content was reintegrated into the Wikipedia page under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license (2022). The version of record as reviewed is:

Osmin Anis; et al. (13 April 2022). "The Kivu Ebola epidemic" (PDF). WikiJournal of Medicine. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.15347/WJM/2022.001. ISSN 2002-4436. Wikidata Q105411509.

Further reading

- Branswell, Helen (20 December 2019). "FDA approves an Ebola vaccine, long in development, for the first time". STAT. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Dokubo, Emily Kainne; Wendland, Annika; Mate, Suzanne E; et al. (September 2018). "Persistence of Ebola virus after the end of widespread transmission in Liberia: an outbreak report". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (9): 1015–1024. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30417-1. PMID 30049622. S2CID 51725253.

- Nanclares, Carolina; Kapetshi, Jimmy; Lionetto, Fanshen; et al. (September 2016). "Ebola Virus Disease, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2014". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (9): 1579–1586. doi:10.3201/eid2209.160354. PMC 4994351. PMID 27533284.

- Claude, Kasereka Masumbuko; Underschultz, Jack; Hawkes, Michael T (October 2018). "Ebola virus epidemic in war-torn eastern DR Congo". The Lancet. 392 (10156): 1399–1401. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32419-X. PMID 30297137.

- "Experimental Ebola vaccines elicit year-long immune response/NIH reports final data from large clinical trial in West Africa". National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH.gov. 11 October 2017.

- Kuhn, Jens; Andersen, Kristian; Baize, Sylvain; et al. (24 November 2014). "Nomenclature- and Database-Compatible Names for the Two Ebola Virus Variants that Emerged in Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2014". Viruses. 6 (11): 4760–4799. doi:10.3390/v6114760. PMC 4246247. PMID 25421896.

- Jones-Konneh, Tracey Elizabeth Claire; Suda, Tomomi; Sasaki, Hiroyuki; et al. (2018). "Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation of Nosocomial Infection among Healthcare Workers during Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in Sierra Leone". The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 245 (4): 231–238. doi:10.1620/tjem.245.231. PMID 30078788.

- "International travel and health". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Rising to the Ebola challenge, again". Nature Microbiology. 3 (9): 965. 16 August 2018. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0243-2. PMID 30115963. S2CID 52019660.

- Lévy, Yves; Lane, Clifford; Piot, Peter; et al. (September 2018). "Prevention of Ebola virus disease through vaccination: where we are in 2018". The Lancet. 392 (10149): 787–790. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31710-0. PMC 6128979. PMID 30104048.

- Dhama, Kuldeep; Karthik, Kumaragurubaran; Khandia, Rekha; et al. (2018). "Advances in Designing and Developing Vaccines, Drugs, and Therapies to Counter Ebola Virus". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 1803. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01803. PMC 6095993. PMID 30147687.

- West, Brandyn R.; Moyer, Crystal L.; King, Liam B.; et al. (11 September 2018). "Structural Basis of Pan-Ebolavirus Neutralization by a Human Antibody against a Conserved, yet Cryptic Epitope". mBio. 9 (5). doi:10.1128/mBio.01674-18. PMC 6134094. PMID 30206174.

- Nakkazi, Esther (August 2018). "DR Congo Ebola virus outbreak: responding in a conflict zone". The Lancet. 392 (10148): 623. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31981-0. PMID 30152332.

- Juan-Giner, Aitana; Tchaton, Marie; Jemmy, Jean-Paul; et al. (2019). "Safety of the rVSV ZEBOV vaccine against Ebola Zaire among frontline workers in Guinea". Vaccine. 37 (48): 7171–7177. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.009. PMID 30266489.

- De Nys, Helene M.; Kingebeni, Placide Mbala; Keita, Alpha K.; et al. (December 2018). "Survey of Ebola Viruses in Frugivorous and Insectivorous Bats in Guinea, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2015–2017". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 24 (12): 2228–2240. doi:10.3201/eid2412.180740. PMC 6256401. PMID 30307845.

- Brett-Major, David; Lawler, James (19 August 2018). "Catching Chances: The Movement to Be on the Ground and Research Ready before an Outbreak". Viruses. 10 (8): 439. doi:10.3390/v10080439. PMC 6116208. PMID 30126221.

- Cousins, Sophie (December 2018). "Violence and community mistrust hamper Ebola response". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (12): 1314–1315. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30658-3. PMID 30385158.

- Owens, Michael D.; Rice, Jason (2019). "The Angolan Pandemic Rapid Response Team: An Assessment, Improvement, and Development Analysis of the First Self-sufficient African National Response Team Curriculum". Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 13 (3): 577–581. doi:10.1017/dmp.2018.122. PMID 30479245. S2CID 53786120.

- Den Boon, Saskia; Marston, Barbara J.; Nyenswah, Tolbert G.; et al. (February 2019). "Ebola Virus Infection Associated with Transmission from Survivors". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 25 (2): 249–255. doi:10.3201/eid2502.181011. PMC 6346469. PMID 30500321.

- Coltart, Cordelia E. M.; Lindsey, Benjamin; Ghinai, Isaac; et al. (26 May 2017). "The Ebola outbreak, 2013–2016: old lessons for new epidemics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1721): 20160297. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0297. PMC 5394636. PMID 28396469.

- Okoror, Lawrence; Kamara, Abdul; Kargbo, Brima; et al. (6 November 2018). "Transplacental transmission: A rare case of Ebola virus transmission". Infectious Disease Reports. 10 (3): 7725. doi:10.4081/idr.2018.7725. PMC 6297901. PMID 30631407.

- Allegranzi, Benedetta; Ivanov, Ivan; Harrell, Mason; et al. (22 November 2018). "Infection Rates and Risk Factors for Infection Among Health Workers During Ebola and Marburg Virus Outbreaks: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 218 (suppl_5): S679–S689. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy435. PMC 6249600. PMID 30202878.

- Ilunga Kalenga, Oly; Moeti, Matshidiso; Sparrow, Annie; et al. (29 May 2019). "The Ongoing Ebola Epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018–2019". New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (4): 373–383. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1904253. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31141654.

- Burki, Talha (November 2019). "DRC getting ready to introduce a second Ebola vaccine". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (11): 1174–1175. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30577-8. ISSN 1474-4457. PMID 31657782.

External links

- World Health Organization Democratic Republic of the Congo crisis information

- World Health Organization Ebola situation reports

- "Ebola outbreak: timeline". Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. 13 September 2016.

- "Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak Uganda Situation Reports". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "Genomic epidemiology of the 2018–19 Ebola epidemic". nextstrain.org. Retrieved 9 November 2019. open source (see Nextstrain)

- "Safety and Health Topics | Ebola". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

Video

- "Donning PPE: Perform Hand Hygiene Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Contact tracing/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 15 September 2018.

| Ebolavirus |

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marburgvirus |

|

||||||||||||||

| Cuevavirus |

|

||||||||||||||

| Dianlovirus |

|

||||||||||||||

| Striavirus |

|

||||||||||||||

| Thamnovirus |

|

||||||||||||||

| Arthropod -borne |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammal -borne |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Local |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

![Mabalako between 16 July and 31 December 2018[71]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cb/Weekly_Ebola_cases_18_Mabalako.svg/225px-Weekly_Ebola_cases_18_Mabalako.svg.png)

![Beni between 23 July 2018 and 28 January 2019[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/02/Weekly_Ebola_cases_18-19_Beni.svg/225px-Weekly_Ebola_cases_18-19_Beni.svg.png)

![Katwa (orange) and Butembo (purple) between 23 July 2018 and 4 February 2019[73]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Weekly_Ebola_cases_18-19_Butembo_und_Katwa.svg/225px-Weekly_Ebola_cases_18-19_Butembo_und_Katwa.svg.png)

![Western Africa Ebola Epidemic (for comparison with current outbreak).[74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/2014_West_Africa_Ebola_Epidemic_-_New_Cases_per_Week.svg/225px-2014_West_Africa_Ebola_Epidemic_-_New_Cases_per_Week.svg.png)

![Ebola (and Marburg virus depicted as green squares) outbreaks on the African continent, both from the Filoviridae family[15][359]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/80/Ebola-and-Marburg-Hemorrhagic-Fevers-Neglected-TropicalDiseases-pntd.0001546.g001.jpg)