Lead–crime hypothesis

The lead–crime hypothesis is a research area that involves a study of the correlation between elevated blood lead levels in children and increased rates of crime, delinquency, and recidivism later in life.

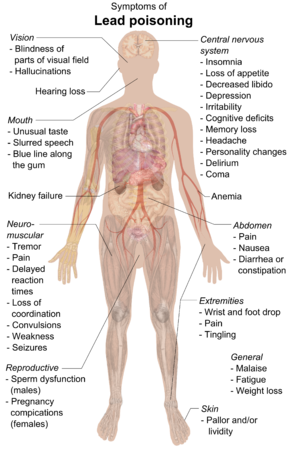

Lead is widely understood to be highly toxic to multiple organs of the body, particularly the brain. Individuals exposed to lead at young ages are more vulnerable to learning disabilities, decreased I.Q.,attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and problems with impulse control, all of which may negatively impact decision-making and lead to the commission of more crimes as these children reach adulthood, especially violent crimes.

Proponents of the lead–crime hypothesis argue that the removal of lead additives from motor fuel, and the consequent decline in children's lead exposure, explains the fall in crime rates in the United States beginning in the 1990s. This hypothesis also offers an explanation of the earlier rise in crime in the preceding decades as the result of increased lead exposure throughout the mid-20th century.

The lead–crime hypothesis is not mutually exclusive with other explanations of the drop in US crime rates such as the legalized abortion and crime effect. Lead exposure during the years in question correlated with exposure to urban poverty, due to close residential or primary school proximity with high-density motor vehicle traffic burning leaded gasoline or from residing in older, poorly maintained housing stock, much of which contained high levels of lead in the form of lead paint, lead solder, or other lead-based building materials; additionally, municipalities with a low taxation base often continued to receive drinking water via degraded lead pipes rather than upgrading to modern infrastructure. The difficulty in measuring the effect of lead exposure on crime rates lies in separating the effect from other indicators of low socioeconomic status such as poorer schools, nutrition, and medical care, exposure to other pollutants, and other variables that are predictive of criminal behavior.

Background

Lead is a naturally occurring metal of bluish-grey color that has been used for multiple purposes in the history of human civilization. Being soft and pliable, as well as resistant to corrosion compared to other metals, has resulted in lead being used for many different items across time. Some of the earliest items made from lead were beads and jewelry dating back to 7th millennium B.C. Its malleability made lead an ideal choice for the Romans to build pipes for transporting water. Furthermore, lead acetate (also referred to as "sugar of lead") has been reported to have been used medicinally in the past. However, it was also noted that exposure to lead may have health consequences. The botanist Nicander was one of the first to write about the uses of lead.Dioscorides would later report that "the mind gives way" in individuals exposed to lead. Nonetheless, despite the hazards posed by lead, its durability made it useful and it was added to items such as glass, paint, and eventually gasoline. The widespread substance is also able to function as a shield against various forms of radiation.

The use of leaded products such as lead paint and leaded gasoline have resulted in higher environmental levels of lead in the air and soil. Lead is also a stable element and does not break down in the environment, so it must be physically removed. Most cases of lead exposure occur via inhalation or ingestion, though transdermal exposure is also possible. Once in the body lead has a half-life of approximately 30 days if in the blood, but can remain in the body for 20 to 30 years if it has accumulated in bones and organs. Expanded scientific investigation into organolead chemistry and the varied ways in which human biology changes due to lead exposure took place throughout the 20th century. Although it has continued to be in wide use even into the 21st century, greater understanding of blood lead levels (BLLs) and other factors have meant that a new scientific consensus has emerged. No safe level of lead in the human bloodstream exists as such; any amount can contribute to neurological problems and other health issues.

Analyses of the role of lead exposure in the brain have been ongoing for the past few decades. Lead can interfere with numerous neurotransmitter systems in the brain, most likely because of its ability to mimic calcium. Elevation of aminolevulinic acid from lead-induced disruption of heme synthesis results in lead poisoning having symptoms similar to acute porphyria. Exposure to lead can also alter brain structure and function. At the behavioral level, exposure to lead has been observed to cause increases in impulsive actions and social aggression, as well as the possibility of developing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Those conditions likely influence personality traits and behavioral choices, with examples including having poor job performance, beginning a pattern of substance abuse, and undergoing teenage pregnancy. Evidence that lead exposure contributes to lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores goes back to a seminal 1979 study in Nature, with later analysis finding the link particularly robust.

The heavy metal lead can be found readily in the environment, especially in urban and industrialized areas. The majority of modern-day environmental lead contamination can be traced back to leaded paint and the addition of tetraethyllead and tetramethyllead to gasoline, though other sources have contributed as well. Though some of the hazards of lead exposure have been documented for centuries, recognition of the hazards posed did not appear to gain much traction until the 1960s with the Senate hearings of Edmund Muskie that would help lead to the phaseout of leaded gasoline and lead-based paint in the 1970s. Blood lead levels would drop in a statistically significant way soon after the phaseout. In the decades since, scientists have concluded that no safe threshold for lead exposure exists.

Though efforts to reduce environmental levels of lead were initially slowed down by the lead industry, the emergence of Clair Patterson in the 1960s would lead to more meaningful changes. The establishment of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the influence of the Consumer Product Safety Commission would help ensure that gasoline and paint could only contain trace amounts of lead. Furthermore, several major legislative acts were passed to help reduce the amount of lead being introduced into the environment, including the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Lead Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act.

The international process of trying to lower the prevalence of lead has been largely spearheaded by the Partnership for Clean Fuels and Vehicles (PCFV). The non-governmental organization partners with major oil companies, various governmental departments, multiple civil society groups, and other such institutions worldwide. Efforts to phase-out lead in transport fuel achieved major gains in over seventy-five nations. In discussions at the 2002 Earth Summit, institutions under the umbrella of the United Nations vowed to emphasize public–private partnerships (PPPs) in order to help developing and transitional countries go unleaded.

Research on lead–crime correlation

After decades of increasing crime across the industrialised world, crime rates started to decline sharply in the 1990s, a trend that continued into the new millennium. Many explanations have been proposed, including situational crime prevention and interactions between many other factors complex, multifactorial causation.

The economists Steven D. Levitt and John J. Donohue III, of the University of Chicago and Stanford University have argued that the decline in U.S. crime rates took place due to the combination of increases in the number of police, hikes in size of the prison population, waning of the spread of crack cocaine, and the widespread legalization of abortion from the 1970s onward. Possible other factors include changes in alcohol consumption. Later studies have upheld many of these findings while disputing others.. However, relatively few studies have noted that crime trends have been broadly consistent internationally, whereas academics have been prone to insularity. For example, trends in drug use in the US are not replicated elsewhere, and while the UK decriminalised abortion five years before the US crime rates there declined five years after those in the US.

Hence the attraction of a theory which could transcend national jurisdictions. While noting that correlation does not imply causation, the fact that in the United States anti-lead efforts took place simultaneously alongside falls in violent crime rates attracted attention from researchers. Changes were not uniform across the country, even while increasingly stringent Environmental Protection Agency rules went into force from 1970s onward. Several areas had far greater lead exposure compared to others for years.

A 2007 report published by The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, authored by Jessica Wolpaw Reyes of Amherst College, found that between 1992 and 2002 the phase-out of lead from gasoline in the U.S. "was responsible for approximately a 56% decline in violent crime". The report noted a significant flaw, cautioning that the findings relating to "murder are not robust if New York and the District of Columbia are included". Nonetheless, the author concluded that "[o]verall, the phase-out of lead and the legalization of abortion appear to have been responsible for significant reductions in violent crime rates." She additionally speculated that by "2020, all adults in their 20s and 30s will have grown up without any direct exposure to gasoline lead during childhood, and their crime rates could be correspondingly lower."]

A 2011 study by the California State University found that "Ridding the world of leaded petrol, with the United Nations leading the effort in developing countries, has resulted in $2.4 trillion in annual benefits, 1.2 million fewer premature deaths, higher overall intelligence and 58 million fewer crimes", according to the United Nations News Centre. The executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Achim Steiner argued that "Although this global effort has often flown below the radar of [the] media and global leaders, it is clear that the elimination of leaded petrol is an immense achievement on par with the global elimination of major deadly diseases."

According to a May 2017 study, lead exposure in childhood substantially increased school suspensions and juvenile detention among boys in Rhode Island, suggesting that the phasing out of leaded gasoline may explain a significant part of the decline in crime in the United States beginning in the 1990s.

A 2018 longitudinal study conducted in New Zealand found only a weak association between childhood lead levels and criminal conviction, which was no longer significant after controlling for sex. In New Zealand, there is no correlation between lead exposure and socioeconomic status, thus social class does not act as a confounder. The authors conclude that "past studies of the association between BLL and crime, in which high BLL and low socioeconomic status were associated, may not have completely overcome confounding". Data from the same cohort was published the next year as well and has been cited in review papers as evidence of lead poisoning having long-lasting consequences for mental health and personality.

A 2022 meta-analysis, which pooled 542 estimates from 24 studies and corrected for publication bias, found that the estimates indicated that "the abatement of lead pollution may be responsible for 7–28% of the fall in homicide in the US," leaving 93-72% unaccounted for. It concluded that "Lead increases crime, but does not explain the majority of the fall in crime observed in some countries in the 20th century. Additional explanations are needed". Another 2022 analysis found that lead abatement was responsible for about 7% of the reduction in offense rates among U.S. cohorts. Most of the remainder was due to "relative cohort size, the prevalence of crime during childhood, and the capacity of families and neighborhoods to socialize children".

See also

- Biosocial criminology

- Environmental toxicology

- Lead abatement

- Lead poisoning

- Organolead chemistry

- Pollution control

- Statistical correlations of criminal behavior

- Tetraethyllead

Further reading

- Carpenter, David O.; Nevin, Rick (February 2010). "Environmental causes of violence" (PDF). Physiology & Behavior. 99 (2): 260–268. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.09.001. PMID 19758571. S2CID 5706643.

- Casciani, Dominic (April 21, 2014). "Did removing lead from petrol spark a decline in crime?". BBC News.

- Drum, Kevin (February 11, 2016). "Lead: America's Real Criminal Element". Mother Jones.

- Feigenbaum, James J.; Muller, Christopher (October 2016). "Lead exposure and violent crime in the early twentieth century" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 62: 51–86. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2016.03.002. S2CID 43223100.

- Firestone, Scott (January 8, 2013). "Does Lead Exposure Cause Violent Crime? The Science is Still Out". Discover.

- Knapp, Alex (January 3, 2013). "How Lead Caused America's Violent Crime Epidemic". Forbes.

- Nevin, Rick (December 19, 2012). "The Answer is Lead Poisoning".

- Nevin, Rick (2016). Lucifer Curves: The Legacy of Lead Poisoning. BookBaby. ASIN B01I3LTR4W.

- Vedantam, Shankar (July 8, 2007). "Research Links Lead Exposure, Criminal Activity". The Washington Post.

- Wakefield, Julie (October 2002). "The lead effect?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (10): A574–A580. doi:10.1289/ehp.110-a574. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1241041. PMID 12361937.