Native American use of fire in ecosystems

Prior to European colonization of the Americas, indigenous peoples used controlled burns to modify the landscape. The controlled fires were part of the environmental cycles and maintenance of wildlife habitats that sustained the cultures and economies of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Parts of what was initially perceived by colonists as "untouched, pristine" wilderness in North America was actually the cumulative result of those occasional managed fires creating an intentional mosaic of grasslands and forests across North America, sustained and managed by the original peoples of the landbase. However, other research indicates "paleo-climate, paleo-ecology and archaeological records suggest that native peoples were not modifying their immediate environments to a great degree."

Radical disruption of Indigenous burning practices occurred with European colonization and forced relocation of those who had historically maintained the landscape. Some colonists understood the traditional use and potential benefits of low-intensity broadcast burns ("Indian-type" fires), but others feared and suppressed them. In the 1880s, impacts of colonization had devastated indigenous populations, and fire exclusion had become more widespread. By the early 20th century, fire suppression had become the official US federal policy. Understanding pre-colonization land management and the traditional knowledge held by the Indigenous peoples who practiced it provides an important basis for current re-engagement with the landscape and is critical for the correct interpretation of the ecological basis for vegetation distribution.

Human-shaped landscape

Authors such as William Henry Hudson, Longfellow, Francis Parkman, and Thoreau contributed to the widespread myth that pre-Columbian North America was a pristine, natural wilderness, "a world of barely perceptible human disturbance.” At the time of these writings, however, enormous tracts of land had already been allowed to succeed to climax due to the reduction in anthropogenic fires after the depopulation of Native peoples from epidemics of diseases introduced by Europeans in the 16th century, forced relocation, and warfare. There is also evidence that climatic conditions again became the dominant driver of wildfire when prehistoric populations in parts of North America abandoned farming around 1400 CE. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans had played a major role in determining the diversity of their ecosystems.

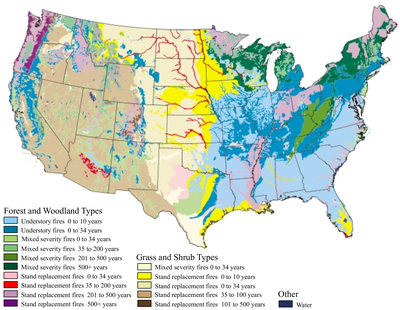

The most significant type of environmental change brought about by Precolumbian human activity was the modification of vegetation. [...] Vegetation was primarily altered by the clearing of forest and by intentional burning. Natural fires certainly occurred but varied in frequency and strength in different habitats. Anthropogenic fires, for which there is ample documentation, tended to be more frequent but weaker, with a different seasonality than natural fires, and thus had a different type of influence on vegetation. The result of clearing and burning was, in many regions, the conversion of forest to grassland, savanna, scrub, open woodland, and forest with grassy openings. (William M. Denevan)

Fire was used to keep large areas of forest and mountains free of undergrowth for hunting or travel, or to create berry patches. The extent of Native American ecological impacts varies across regions and time periods:

In parts of the Americas, Indigenous people had major ecological impacts. For example, the Maya deforested much of the Meso-American landscape, supporting a large, settled population with agriculture. In interior areas of eastern North America, some Native groups farmed intensively around large villages for at least the few centuries immediately preceding European arrival. However, [...] painting all regions with one “human brush” ignores “great geographical and temporal variation in the importance of human versus environmental controls on ecosystem patterns and processes. [...] We conducted a more-detailed analysis for the coastal area for the last 2,000 years, employing 21 palaeoecological records and archaeological data from >1,800 sites. During the Middle to Late Woodland, the period of highest Native American populations of the last 14,000 years, there is no pollen or charcoal evidence for regionally extensive human impacts or open-land vegetation. Meanwhile, the archaeological data indicate that horticulture played a minor role in subsistence. Thus, there is no evidence for forest clearance, widespread farming or increased fire associated with larger Native populations.

Grasslands and savannas

When first encountered by Europeans, many ecosystems were the result of repeated fires every one to three years, resulting in the replacement of forests with grassland or savanna, or opening up the forest by removing undergrowth.Terra preta soils, created by slow burning, are found mainly in the Amazon basin, where estimates of the area covered range from 0.1 to 0.3%, or 6,300 to 18,900 km² of low forested Amazonia to 1.0% or more.

There is some argument about the effect of human-caused burning when compared to lightning in western North America. Eyewitness accounts of extensive pre-settlement prairie in the 1600s, and the rapid conversion of extensive prairie areas to woodland on settlement, combined with accounts of the efforts made to make indigenous prairie burning practices illegal in Canada and the USA, all point to widespread pre-settlement control of fire with the intent to maintain and expand prairie areas. As Emily Russell (1983) has pointed out, “There is no strong evidence that Indians purposely burned large areas....The presence of Indians did, however, undoubtedly increase the frequency of fires above the low numbers caused by lightning.” As might be expected, Indian fire use had its greatest impact “in local areas near Indian habitations.”

Reasons for and benefits of burning

Reasons given for controlled burns in pre-contact ecosystems are numerous and well thought out. They include:

- Facilitating agriculture by rapidly recycling mineral-rich ash and biomass.

- Increasing nut production in wild/wildcrafted orchards by darkening the soil layer with carbonized leaf litter, decreasing localized albedo, and increasing the average temperature in spring, when nut flowers and buds would be sensitive to late frosts.

- Promoting the regrowth of fire-adapted food and utility plants by initiating seed germination or coppicing – shrub species like osier, willow, hazel, Rubus, and others have their lifespan extended and productivity increased through controlled cutting (burning) of branch stems.

- Facilitating hunting by clearing underbrush and fallen limbs, allowing for more silent passage and stalking through the forest, as well as increasing visibility of game and clear avenues for projectiles.

- Facilitating travel by reducing impassible brambles, underbrush and thickets.

- Decreasing the risk of larger scale, catastrophic fires which consume decades of built-up fuel.

- Increasing population of game animals by creating habitat in grasslands or increasing understory habitat of fire-adapted grass forage (in other words, wildcrafted pasturage) for deer, lagomorphs, bison, extinct grazing megafauna like mammoths, rhinoceros, camelids and others, the nearly extinct prairie chicken; and the populations of nut-consuming species like rodents, turkey and bear and notably the passenger pigeon through increased nut production (above); as well as the populations of their predators, i.e. mountain lions, lynx, bobcats, wolves, etc.

- Increasing the frequency of regrowth of beneficial food and medicine plants, like clearing-adapted species like cherry, plum, and others.

- Decreasing tick and biting insect populations by destroying overwintering instars and eggs.

- Smoke density cools river temperatures and decreases evapotranspiration by plants, which increases river flow.

- Rivers cooled by smoke density alert salmon that they may begin upstream migration.

Impacts of European settlement

By the time that European explorers first arrived in North America, millions of acres of "natural" landscapes were already manipulated and maintained for human use. Fires indicated the presence of humans to many European explorers and settlers arriving on ship. In San Pedro Bay in 1542, chaparral fires provided that signal to Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, and later to others across all of what would be named California.

In the American west, it is estimated that 456,500 acres (184,737 ha) burned annually pre-settlement in what is now Oregon and Washington.

By the 17th century, native populations were greatly affected by the genocidal structure of settler colonialism. Many colonists often either deliberately set wildfires and/or allowed out of control fires to "run free." Also, sheep and cattle owners, as well as shepherds and cowboys, often set the alpine meadows and prairies on fire at the end of the grazing season to burn the dried grasses, reduce brush, and kill young trees, as well as encourage the growth of new grasses for the following summer and fall grazing season. Native people were forced off their traditional landbases or killed, and traditional land management practices were eventually made illegal by settler governance.

By the 19th century, many Indigenous nations had been forced to sign treaties with the federal government and relocate to reservations, which were sometimes hundreds of miles away from their ancestral homelands. In addition to violent and forced removal, fire suppression would become part of colonial methods of removal and genocide. As sociologist Kari Norgaard has shown, "Fire suppression was mandated by the very first session of the California Legislature in 1850 during the apex of genocide in the northern part of the state." For example, the Karuk peoples of Northern California "burn [the forest] to enhance the quality of forest food species like elk, deer, acorns, mushrooms, and lilies, as well as basketry materials such as hazel and willow, but also keep travel routes open.” When such relationships to their environment were made illegal through fire suppression, it would have dramatic consequences on their methods of relating to one another, their environment, their food sources, and their educational practices. Thus, many scholars have argued that fire suppression can be seen as a form of "Colonial Ecological Violence," "which results in particular risks and harms experienced by Native peoples and communities."

Through the turn of the 20th century, settlers continued to use fire to clear the land of brush and trees in order to make new farm land for crops and new pastures for grazing animals – the North American variation of slash and burn technology – while others deliberately burned to reduce the threat of major fires – the so‑called "light burning" technique. Light burning is also been called "Paiute forestry," a direct but derogatory reference to southwestern tribal burning habits. The ecological impacts of settler fires were vastly different than those of their Native American predecessors, and further, Native fire practices were largely made illegal at the beginning of the 20th Century with the passage of the Weeks Act in 1911.

Altered fire regimes

Removal of indigenous populations and their controlled burning practices have resulted in major ecological changes, including increased severity of wild fires, especially in combination with Climate change. Attitudes towards Native American-type burning have shifted in recent times, and Tribal agencies and organizations, now with fewer restrictions placed on them by the colonists, have resumed their traditional use of fire practices in a modern context by reintroducing fire to fire-adapted ecosystems, on and adjacent to, tribal lands. Many foresters and ecologists have also recognized the importance of Native fire practices. They are now learning from traditional fire practitioners and using controlled burns to reduce fuel accumulations, change species composition, and manage vegetation structure and density for healthier forests and rangelands.

Archaeological Studies

Jemez Mountains

A study of the anthropological use of fire in the Jemez Mountains was conducted using charcoal samples in the soil and fire scars in tree rings. The study found that increases in low severity ecological fires were positively correlated with population changes, rather than climate changes. The population of the region. The study also found that there were more herbivores present at times of increased burning from fungal evidence. The researchers also found that the landscape fires that occurred during the period of ancient settlement were less severe than modern wildfires in the region.

Stockbridge, MA

A study of sites in Massachusetts that were inhabited from 3000 BCE to 1000 CE found that the precedence of low severity landscape fires was correlated with periods of habitation by looking at charcoal sentiment samples. The research also found that periods of intense burning were correlated with increases in chestnut trees through looking at fossilized pollen samples. The study did not find any archaeological evidence that the fires were intentionally set, but a combination of historic accounts from the region, the correlation with habitation, and the incentive for burning to increase nut producing trees, lead to the inference that it is likely these were anthropogenic fires.

Upper Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee

A study of charcoal and pollen deposits in Tennessee found regular anthropogenic fires were occurring from 3000 years ago to 200 years ago. However, the study found no evidence that the fires changed the overall vegetation that was present in the region.

Cliff Palace Pond, Kentucky

Research conducted by Paul Delcort in Kentucky pioneered the study of anthropogenic fires in the United States using archaeological techniques. These studies looked at pollen and charcoal sediment samples from sites in Kentucky to chart fires over time due to climate changes and human activity. The study found that between 1000 BCE and 1800 CE there was increased charcoal concentrations, suggesting frequent low severity fires. During this same period there was an increase in pollen from fire adapted tree species such as oak, chestnut, and hickory. There was also an increase in pollen from sunflowers and goose foot in forest areas which may suggest that there was food production in burned ecosystems. The studies found that fires which coincided with human habitation prior to fire suppression resulted in a diverse patchwork ecosystem with many plants that could be used by humans.

West Virginia

A Paleoarchealogical study of the Ohio River Valley in West Virginia found that ecosystems experienced coevolution with humans due to land management practices. The study concluded that these practices included burning and land clearing. They found that these practices altered soil carbon cycling and the diversity of plant species. They found that the use of fire decreased biomass, increased charcoal abundance, and potentially led to more usable vegetation.

See also

Further reading

- Blackburn, Thomas C. and Kat Anderson (eds.). 1993. Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press. Several chapters on Indian use of fire, one by Henry T. Lewis as well as his final “In Retrospect.”

- Bonnicksen, Thomas M. 2000. America's Ancient Forests: From the Ice Age to the Age of Discovery. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Especially see chapter 7 “Fire Masters” pp. 143–216.

- Boyd, Robert T. (ed.). 1999. Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, ISBN 978-0-87071-459-7. An excellent series of papers about Indian burning in the West.

- Lewis, Henry T. 1982. A Time for Burning. Occasional Publication No. 17. Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta, Boreal Institute for Northern Studies. 62 pages.

- Lutz, Harold J. 1959. Aboriginal Man and White Men as Historical Causes of Fires in the Boreal Forest, with Particular Reference to Alaska. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin No. 65. New Haven, CT: Yale University. 49 pages.

- Pyne, Stephen J. 1982. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 654 pages. See Chapter 2 “The Fire from Asia” pp. 66–122.

- Russell, Emily W.B. 1983. "Indian‑Set Fires in the Forests of the Northeastern United States." Ecology, Vol. 64, #1 (Feb): 78–88.l

- Stewart, Omer C. with Henry T. Lewis and of course M. Kat Anderson (eds.). 2002. Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 364 pages.

- Vale, Thomas R. (ed.). 2002. Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape. Washington, DC: Island Press. An interesting set of articles that generally depict landscape changes as natural events rather that Indian caused.

- Whitney, Gordon G. 1994. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain: A History of Environmental Change in Temperate North America 1500 to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press. See especially Chapter 5 “Preservers of the Ecological Balance Wheel”, pp. 98–120.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Agriculture.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Agriculture.

| History | |

|---|---|

| Science | |

| Components | |

| Individual fires | |

| Crime | |

| People | |

| Culture | |

| Organizations | |

| Other | |

| Components | |

|---|---|

| Topics | |

| Early starters | |

| Modern starters | |

| Other equipment | |

| Related articles | |