- 17q12 microdeletion syndrome

- Childhood disintegrative disorder

- Dup15q

- Fragile X syndrome

- High-functioning autism

- Hikikomori

- Low-functioning autism

- Pervasive developmental disorder

- Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified

- SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability

- Autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder

| Autism | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

| Repetitively stacking or lining up objects is a common trait associated with autism. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, pediatrics, occupational medicine |

| Symptoms | Difficulties in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and the presence of repetitive behavior or restricted interests |

| Complications | Social isolation, educational and employment problems,anxiety,stress,bullying, depression,self-harm |

| Onset | Early childhood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Multifactorial, with many uncertain factors |

| Risk factors | Family history, certain genetic conditions, having older parents, certain prescribed drugs, perinatal and neonatal health issues |

| Diagnostic method | Based on combination of clinical observation of behavior and development and comprehensive diagnostic testing completed by a team of qualified professionals (including clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, pediatricians, and speech-language pathologists) |

| Differential diagnosis | Intellectual disability, anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, Rett syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizoid personality disorder, selective mutism, schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, Einstein syndrome, PTSD, learning disorders (mainly speech disorders), social anxiety |

| Management | Applied behavior analysis, cognitive behavioral therapy, occupational therapy, psychotropic medication,speech–language pathology |

| Frequency |

|

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and social interaction, and repetitive or restricted patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities, which can include hyper- and hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

Psychiatry has traditionally classified autism as a mental disorder, while the autism rights movement and a small but increasing number of researchers see autism as part of neurodiversity, the natural diversity in human thinking and experience, with strengths, differences, and weaknesses. From this point of view, autistic people often still have a disability, but need to be accommodated, rather than cured. This perspective has led to significant controversy among those who are autistic alongside advocates, practitioners, and charities.

There are many theories about what causes autism; it is highly heritable and believed to be mainly genetic, but many genes are involved, and environmental factors may also be relevant. The syndrome frequently co-occurs with other conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy, and intellectual disability. Disagreements continue about questions such as what should be included as part of the diagnosis, whether there are meaningful subtypes of autism, and the significance of autism-associated traits in the wider population. The combination of broader criteria and increased awareness has led to a trend of steadily increasing estimates of autism prevalence, causing a misconception that there is an autism epidemic and perpetuating the myth that it is caused by vaccines.

There are many forms of therapy, such as speech and occupational therapy, that may help autistic people. Some forms of therapy, such as applied behavior analysis, are controversial in the autism rights movement, with many advocates considering them unhelpful and unethical. Intervention can require accommodations such as alternative modes of communication. The use of medicine is usually focused on associated conditions such as epilepsy or treating certain symptoms.

Classification

Spectrum model

Before the DSM-5 (2013) and ICD-11 (2022) diagnostic manuals were adopted, what is now called ASD was found under the diagnostic category pervasive developmental disorder. The previous system relied on a set of closely related and overlapping diagnoses such as Asperger syndrome and Kanner syndrome. This created unclear boundaries between the terms, so for the DSM-5 and ICD-11, a spectrum approach was taken. The new system is also more restrictive, meaning fewer people now qualify for diagnosis.

The DSM-5 and ICD-11 use different categorisation tools to define this spectrum. DSM-5 uses a "level" system, which ranks how in need of support the patient is, while the ICD-11 system has two axes: intellectual impairment and language impairment, as these are seen as the most crucial factors.

It is now known that autism is a highly variable neurodevelopmental disorder that is generally thought to cover a broad and deep spectrum, manifesting very differently from one person to another. Some have high support needs, may be non-speaking, and experience developmental delays; this is more likely with other co-existing diagnoses. Others have relatively low support needs; they may have more typical speech-language and intellectual skills but atypical social/conversation skills, narrowly focused interests, and wordy, pedantic communication. They may still require significant support in some areas of their lives. The spectrum model should not be understood as a continuum running from mild to severe, but instead means that autism can present very differently in each individual. How a person presents can depend on context, and may vary over time.

While the DSM and ICD are greatly influenced by each other, there are also differences. For example, Rett syndrome was included in ASD in the DSM-5, but in the ICD-11 it was excluded and placed in the chapter on Developmental Anomalies. The ICD and the DSM change over time, and there has been collaborative work toward a convergence of the two since 1980 (when DSM-III was published and ICD-9 was current), including more rigorous biological assessment—in place of historical experience—and a simplification of the classification system.

ICD

The World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision), ICD-11, was released in June 2018 and came into full effect as of January 2022. It describes ASD as follows:

Autism spectrum disorder is characterised by persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and to sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication, and by a range of restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests or activities that are clearly atypical or excessive for the individual's age and sociocultural context. The onset of the disorder occurs during the developmental period, typically in early childhood, but symptoms may not become fully manifest until later, when social demands exceed limited capacities. Deficits are sufficiently severe to cause impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and are usually a pervasive feature of the individual's functioning observable in all settings, although they may vary according to social, educational, or other context. Individuals along the spectrum exhibit a full range of intellectual functioning and language abilities.

— ICD-11, chapter 6, section A02

ICD-11 was produced by professionals from 55 countries out of the 90 involved and is the most widely used reference worldwide.

DSM

The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), released in 2022, is the current version of the DSM. It is the predominant mental health diagnostic system used in the United States and Canada, and is often used in Anglophone countries.

Its fifth edition, DSM-5, released in May 2013, was the first to define ASD as a single diagnosis, which is still the case in the DSM-5-TR. ASD encompasses previous diagnoses, including Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, PDD-NOS, and the range of diagnoses that included the word autism. Rather than distinguishing among these diagnoses, the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR adopt a dimensional approach to diagnosing disorders that fall underneath the autism spectrum umbrella in one diagnostic category. Within this category, the DSM-5 and the DSM include a framework that differentiates each individual by dimensions of symptom severity, as well as by associated features (i.e., the presence of other disorders or factors that likely contribute to the symptoms, other neurodevelopmental or mental disorders, intellectual disability, or language impairment). The symptom domains are social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors, with the option of a separate severity—the negative impact of the symptoms on the individual—being specified for each domain, rather than an overall severity. Before the DSM-5, the DSM separated social deficits and communication deficits into two domains. Further, the DSM-5 changed to an onset age in the early developmental period, with a note that symptoms may manifest later when social demands exceed capabilities, rather than the previous, more restricted three years of age. These changes remain in the DSM-5-TR.

Common characteristics

Pre-diagnosis

For many autistic people, characteristics first appear during infancy or childhood and follow a steady course without remission (different developmental timelines are described in more detail below). Autistic people may be severely impaired in some respects but average, or even superior, in others.

Clinicians consider assessment for ASD when a patient shows:

- regular difficulties in social interaction or communication

- restricted or repetitive behaviors (often called "stimming")

- resistance to changes or restricted interests

These features are typically assessed with the following, when appropriate:

- problems in obtaining or sustaining employment or education

- difficulties in initiating or sustaining social relationships

- connections with mental health or learning disability services

- a history of neurodevelopmental conditions (including learning disabilities and ADHD) or mental health conditions.

There are many signs associated with autism; the presentation varies widely:

Common signs for autistic spectrum disorder - avoidance of eye-contact

- little or no babbling as an infant

- not showing interest in indicated objects

- delayed language skills (e.g. having a smaller vocabulary than peers or difficulty expressing themselves in words)

- reduced interest in other children or caretakers, possibly with more interest in objects

- difficulty playing reciprocal games (e.g. peek-a-boo)

- hyper- or hypo-sensitivity to or unusual response to the smell, texture, sound, taste, or appearance of things

- resistance to changes in routine

- repetitive, limited, or otherwise unusual usage of toys (e.g. lining up toys)

- repetition of words or phrases (echolalia)

- repetitive motions or movements, including stimming

- self-harming

Broader autism phenotype

The broader autism phenotype (BAP) describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic traits, such as avoiding eye contact and stimming.

Social and communication skills

In social contexts, autistic people may respond and behave differently than people without ASD.

Impairments in social skills present many challenges for autistic people. Deficits in social skills may lead to problems with friendships, romantic relationships, daily living, and vocational success. One study that examined the outcomes of autistic adults found that, compared to the general population, autistic people were less likely to be married, but it is unclear whether this outcome was due to deficits in social skills, intellectual impairment, or another reason. One factor is likely discrimination against autistic people, which is perpetuated by myths—for example, the myth that they have no empathy.

Until 2013, deficits in social function and communication were considered two separate symptom domains of autism. The current social communication domain criteria for autism diagnosis require individuals to have deficits across three social skills: social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communication, and developing and sustaining relationships.

A range of social-emotional reciprocity difficulties (an individual's ability to naturally engage in social interactions) may be present. Autistic individuals may lack mutual sharing of interests; many autistic children prefer not to play or interact with others. They may lack awareness or understanding of other people's thoughts or feelings: a child may get too close to peers (entering their personal space) without noticing that this makes them uncomfortable. They may also engage in atypical behaviors to gain attention: a child may push a peer to gain attention before starting a conversation.

Older autistic children and adults perform worse on tests of face and emotion recognition than non-autistic individuals, although this may be due to the prevalence of alexithymia in autistic people rather than autism itself.

Autistic people experience deficits in their ability to develop, maintain, and understand relationships, as well as difficulties adjusting behavior to fit social contexts. ASD presents with impairments in pragmatic communication skills, such as difficulty initiating a conversation or failure to consider the listener's interests to sustain a conversation. The ability to be focused exclusively on one topic in communication is known as monotropism, and can be compared to "tunnel vision". It is common for autistic people to communicate strong interest in a specific topic, speaking in lesson-like monologues about their passion instead of enabling reciprocal communication. What may look like self-involvement or indifference to others stems from a struggle to recognize or remember that other people have their own personalities, perspectives, and interests. Another difference in pragmatic communication skills is that autistic people may not recognize the need to control the volume of their voice in different social settings; for example, they may speak loudly in libraries or movie theaters.

Autistic people display atypical nonverbal behaviors or have difficulties with nonverbal communication. They may make infrequent eye contact: an autistic person may not make eye contact when called by name, or may avoid eye contact with an observer. Aversion of gaze can also be seen in anxiety disorders, but poor eye contact in autistic children is not due to shyness or anxiety; rather, it is overall diminished in quantity. Autistic people may struggle with both production and understanding of facial expressions. They often do not know how to recognize emotions from others' facial expressions, or may not respond with appropriate facial expressions. They may have trouble recognizing subtle expressions of emotion and identifying what various emotions mean for the conversation. A defining feature is that autistic people have social impairments and often lack intuitions about others that many people take for granted. Temple Grandin, an autistic woman involved in autism activism, described her inability to understand the social communication of neurotypicals, or people with typical neural development, as leaving her feeling "like an anthropologist on Mars". They may also not pick up on body language or social cues such as eye contact and facial expressions if they provide more information than the person can process at that time. They struggle with understanding the context and subtext of conversational or printed situations, and have trouble forming resulting conclusions about the content. This also results in a lack of social awareness and atypical language expression. How facial expressions differ between those on the autism spectrum and neurotypical individuals is not clear. Further, at least half of autistic children have unusual prosody.

Autistic people may also experience difficulties with verbal communication. Differences in communication may be present from the first year of life, and may include delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and vocal patterns that are not synchronized with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences, and are more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia).Joint attention seems to be necessary for functional speech, and deficits in joint attention seem to distinguish autistic infants. For example, they may look at a pointing hand instead of the object to which the hand is pointing, and they consistently fail to point at objects in order to comment on or share an experience. Autistic children may have difficulty with imaginative play and with developing symbols into language. Some autistic linguistic behaviors include repetitive or rigid language, and restricted interests in conversation. For example, a child might repeat words or insist on always talking about the same subject. Echolalia may also be present in autistic individuals, for example by responding to a question by repeating the inquiry instead of answering. Language impairment is also common in autistic children, but is not part of a diagnosis. Many autistic children develop language skills at an uneven pace where they easily acquire some aspects of communication, while never fully developing others, such as in some cases of hyperlexia. In some cases, individuals remain completely nonverbal throughout their lives. The CDC estimated that around 40% of autistic children don't speak at all, although the accompanying levels of literacy and nonverbal communication skills vary.

Restricted and repetitive behaviors

ASD includes a wide variety of characteristics. Some of these include behavioral characteristics which widely range from slow development of social and learning skills to difficulties creating connections with other people. Autistic individuals may experience these challenges with forming connections due to anxiety or depression, which they are more likely to experience, and as a result isolate themselves.

Other behavioral characteristics include abnormal responses to sensations (such as sights, sounds, touch, taste and smell) and problems keeping a consistent speech rhythm. The latter problem influences an individual's social skills, leading to potential problems in how they are understood by communication partners. Behavioral characteristics displayed by autistic people typically influence development, language, and social competence. Behavioral characteristics of autistic people can be observed as perceptual disturbances, disturbances of development rate, relating, speech and language, and motility.

The second core symptom of autism spectrum is a pattern of restricted and repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. In order to be diagnosed with ASD under the DSM-5-TR, a person must have at least two of the following behaviors:

- Repetitive behaviors – Repetitive behaviors such as rocking, hand flapping, finger flicking, head banging, or repeating phrases or sounds. These behaviors may occur constantly or only when the person gets stressed, anxious or upset. These behaviors are also known as stimming.

- Resistance to change – A strict adherence to routines such as eating certain foods in a specific order, or taking the same path to school every day. The individual may become distressed if there is any change or disruption to their routine.

- Restricted interests – An excessive interest in a particular activity, topic, or hobby, and devoting all their attention to it. For example, young children might completely focus on things that spin and ignore everything else. Older children might try to learn everything about a single topic, such as the weather or sports, and perseverate or talk about it constantly.

- Sensory reactivity – An unusual reaction to certain sensory inputs such as having a negative reaction to specific sounds or textures, being fascinated by lights or movements or having an apparent indifference to pain or heat.

Autistic individuals can display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, which the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) categorizes as follows.

- Stereotyped behaviors: Repetitive movements, such as hand flapping, head rolling, or body rocking.

- Compulsive behaviors: Time-consuming behaviors intended to reduce anxiety, that an individual feels compelled to perform repeatedly or according to rigid rules, such as placing objects in a specific order, checking things, or handwashing.

- Sameness: Resistance to change; for example, insisting that the furniture not be moved or refusing to be interrupted.

- Ritualistic behavior: Unvarying pattern of daily activities, such as an unchanging menu or a dressing ritual. This is closely associated with sameness and an independent validation has suggested combining the two factors.

- Restricted interests: Interests or fixations that are abnormal in theme or intensity of focus, such as preoccupation with a single television program, toy, or game.

- Self-injury: Behaviors such as eye-poking, skin-picking, hand-biting and head-banging.

Self-injury

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) are relatively common in autistic people, and can include head-banging, self-cutting, self-biting, and hair-pulling. Some of these behaviors can result in serious injury or death. Following are theories about the cause of self-injurious behavior in children with developmental delay, including autistic individuals:

- Frequency and/or continuation of self-injurious behavior can be influenced by environmental factors (e.g. reward in return for halting self-injurious behavior). However this theory is not applicable to younger children with autism. There is some evidence that frequency of self-injurious behavior can be reduced by removing or modifying environmental factors that reinforce this behavior.

- Higher rates of self-injury are also noted in socially isolated individuals with autism. Studies have shown that socialization skills are related factors to self injurious behavior for individuals with autism.

- Self-injury could be a response to modulate pain perception when chronic pain or other health problems that cause pain are present.

- An abnormal basal ganglia connectivity may predispose to self-injurious behavior.

Other features

Autistic individuals may have symptoms that do not contribute to the official diagnosis, but that can affect the individual or the family.

- Some individuals with ASD show unusual or notable abilities, ranging from splinter skills (such as the memorization of trivia) to rare talents in mathematics, music or artistic reproduction, which in exceptional cases are considered a part of the savant syndrome. One study describes how some individuals with ASD show superior skills in perception and attention, relative to the general population.Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of autistic people, and are considered core features by some.

- More generally, autistic people tend to show a 'spiky skills profile', with strong abilities in some areas contrasting with much weaker abilities in others.

- Differences between the previously recognized disorders under the autism spectrum are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for sensation seeking (for example, rhythmic movements). An estimated 60–80% of autistic people have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking; deficits in motor coordination are pervasive across ASD and are greater in autism proper.

- Pathological demand avoidance can occur. People with this set of autistic symptoms are more likely to refuse to do what is asked or expected of them, even to activities they enjoy.

- Unusual or atypical eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator. Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food refusal also occur.

- There is tentative evidence that gender dysphoria occurs more frequently in autistic people (see Autism and LGBT identities). As well as that, a 2021 anonymized online survey of 16–90 year-olds revealed that autistic males are more likely to identify as bisexual, while autistic females are more likely to identify as homosexual.

Possible causes

Exactly what causes autism remains unknown. It was long mostly presumed that there is a common cause at the genetic, cognitive, and neural levels for the social and non-social components of ASD's symptoms, described as a triad in the classic autism criteria. But it is increasingly suspected that autism is instead a complex disorder whose core aspects have distinct causes that often cooccur. While it is unlikely that ASD has a single cause, many risk factors identified in the research literature may contribute to ASD development. These include genetics, prenatal and perinatal factors (meaning factors during pregnancy or very early infancy), neuroanatomical abnormalities, and environmental factors. It is possible to identify general factors, but much more difficult to pinpoint specific ones. Given the current state of knowledge, prediction can only be of a global nature and therefore requires the use of general markers.

Biological subgroups

Research into causes has been hampered by the inability to identify biologically meaningful subgroups within the autistic population and by the traditional boundaries between the disciplines of psychiatry, psychology, neurology and pediatrics. Newer technologies such as fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging can help identify biologically relevant phenotypes (observable traits) that can be viewed on brain scans, to help further neurogenetic studies of autism; one example is lowered activity in the fusiform face area of the brain, which is associated with impaired perception of people versus objects. It has been proposed to classify autism using genetics as well as behavior. (For more, see Brett Abrahams)

Genetics

Autism has a strong genetic basis, although the genetics of autism are complex and it is unclear whether ASD is explained more by rare mutations with major effects, or by rare multi-gene interactions of common genetic variants. Complexity arises due to interactions among multiple genes, the environment, and epigenetic factors which do not change DNA sequencing but are heritable and influence gene expression. Many genes have been associated with autism through sequencing the genomes of affected individuals and their parents. However, most of the mutations that increase autism risk have not been identified. Typically, autism cannot be traced to a Mendelian (single-gene) mutation or to a single chromosome abnormality, and none of the genetic syndromes associated with ASD have been shown to selectively cause ASD. Numerous candidate genes have been located, with only small effects attributable to any particular gene. Most loci individually explain less than 1% of cases of autism. As of 2018, it appeared that between 74% and 93% of ASD risk is heritable. After an older child is diagnosed with ASD, 7% to 20% of subsequent children are likely to be as well. If parents have one autistic child, they have a 2% to 8% chance of having a second child who is autistic. If the autistic child is an identical twin, the other will be affected 36% to 95% of the time. A fraternal twin is affected up to 31% of the time. The large number of autistic people with unaffected family members may result from spontaneous structural variation, such as deletions, duplications or inversions in genetic material during meiosis. Hence, a substantial fraction of autism cases may be traceable to genetic causes that are highly heritable but not inherited: that is, the mutation that causes the autism is not present in the parental genome.

As of 2018, understanding of genetic risk factors had shifted from a focus on a few alleles to an understanding that genetic involvement in ASD is probably diffuse, depending on a large number of variants, some of which are common and have a small effect, and some of which are rare and have a large effect. The most common gene disrupted with large effect rare variants appeared to be CHD8, but less than 0.5% of autistic people have such a mutation. The gene CHD8 encodes the protein chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8, which is a chromatin regulator enzyme that is essential during fetal development, CHD8 is an ATP dependent enzyme. The protein contains an Snf2 helicase domain that is responsible for the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP. CHD8 encodes for a DNA helicase that function as a transcription repressor by remodeling chromatin structure by altering the position of nucleosomes. CHD8 negatively regulates Wnt signaling. Wnt signaling is important in the vertebrate early development and morphogenesis. It is believed that CHD8 also recruits the linker histone H1 and causes the repression of β-catenin and p53 target genes. The importance of CHD8 can be observed in studies where CHD8-knockout mice died after 5.5 embryonic days because of widespread p53 induced apoptosis. Some studies have determined the role of CHD8 in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). CHD8 expression significantly increases during human mid-fetal development. The chromatin remodeling activity and its interaction with transcriptional regulators have shown to play an important role in ASD aetiology. The developing mammalian brain has a conserved CHD8 target regions that are associated with ASD risk genes. The knockdown of CHD8 in human neural stem cells results in dysregulation of ASD risk genes that are targeted by CHD8. Recently CD8 has been associated to the regulation of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and the regulation of X chromosome inactivation (XCI) initiation, via regulation of Xist long non-coding RNA, the master regulator of XCI, though competitive binding to Xist regulatory regions.

Some ASD is associated with clearly genetic conditions, like fragile X syndrome; however, only around 2% of autistic people have fragile X. Hypotheses from evolutionary psychiatry suggest that these genes persist because they are linked to human inventiveness, intelligence or systemising.

Current research suggests that genes that increase susceptibility to ASD are ones that control protein synthesis in neuronal cells in response to cell needs, activity and adhesion of neuronal cells, synapse formation and remodeling, and excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitter balance. Therefore, despite up to 1000 different genes thought to contribute to increased risk of ASD, all of them eventually affect normal neural development and connectivity between different functional areas of the brain in a similar manner that is characteristic of an ASD brain. Some of these genes are known to modulate production of the GABA neurotransmitter which is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nervous system. These GABA-related genes are under-expressed in an ASD brain. On the other hand, genes controlling expression of glial and immune cells in the brain e.g. astrocytes and microglia, respectively, are over-expressed which correlates with increased number of glial and immune cells found in postmortem ASD brains. Some genes under investigation in ASD pathophysiology are those that affect the mTOR signaling pathway which supports cell growth and survival.

All these genetic variants contribute to the development of the autistic spectrum; however, it cannot be guaranteed that they are determinants for the development.

ASD may be under-diagnosed in women and girls due to an assumption that it is primarily a male condition, but genetic phenomena such as imprinting and X linkage have the ability to raise the frequency and severity of conditions in males, and theories have been put forward for a genetic reason why males are diagnosed more often, such as the imprinted brain hypothesis and the extreme male brain theory.

Early life

Several prenatal and perinatal complications have been reported as possible risk factors for autism. These risk factors include maternal gestational diabetes, maternal and paternal age over 30, bleeding during pregnancy after the first trimester, use of certain prescription medication (e.g. valproate) during pregnancy, and meconium in the amniotic fluid. While research is not conclusive on the relation of these factors to autism, each of these factors has been identified more frequently in children with autism, compared to their siblings who do not have autism, and other typically developing youth. While it is unclear if any single factors during the prenatal phase affect the risk of autism, complications during pregnancy may be a risk.

There are also studies being done to test if certain types of regressive autism have an autoimmune basis.

Maternal nutrition and inflammation during preconception and pregnancy influences fetal neurodevelopment. Intrauterine growth restriction is associated with ASD, in both term and preterm infants. Maternal inflammatory and autoimmune diseases may damage fetal tissues, aggravating a genetic problem or damaging the nervous system.

Exposure to air pollution during child pregnancy, especially heavy metals and particulates, may increase the risk of autism.Environmental factors that have been claimed without evidence to contribute to or exacerbate autism include certain foods, infectious diseases, solvents, PCBs, phthalates and phenols used in plastic products, pesticides, brominated flame retardants, alcohol, smoking, illicit drugs, vaccines, and prenatal stress. Some, such as the MMR vaccine, have been completely disproven.

Disproven vaccine hypothesis

Parents may first become aware of ASD symptoms in their child around the time of a routine vaccination. This has led to unsupported and disproven theories blaming vaccine "overload", a vaccine preservative, or the MMR vaccine for causing autism spectrum disorder. In 1998, British physician and academic Andrew Wakefield led a fraudulent, litigation-funded study that suggested that the MMR vaccine may cause autism. This conjecture suggested that autism results from brain damage caused either by the MMR vaccine itself, or by thimerosal, a vaccine preservative. No convincing scientific evidence supports these claims. They are biologically implausible, and further evidence continues to refute them, including the observation that the rate of autism continues to climb despite elimination of thimerosal from routine childhood vaccines. A 2014 meta-analysis examined ten major studies on autism and vaccines involving 1.25 million children worldwide; it concluded that neither the MMR vaccine, which has never contained thimerosal, nor the vaccine components thimerosal or mercury, lead to the development of ASDs. Despite this, misplaced parental concern has led to lower rates of childhood immunizations, outbreaks of previously controlled childhood diseases in some countries, and the preventable deaths of several children.

Etiological hypotheses

Several hypotheses have been presented that try to explain how and why autism develops by integrating known causes (genetic and environmental effects) and findings (neurobiological and somatic). Some are more comprehensive, such as the Pathogenetic Triad, which proposes and operationalizes three core features (an autistic personality, cognitive compensation, neuropathological burden) that interact to cause autism, and the Intense World Theory, which explains autism through a hyper-active neurobiology that leads to an increased perception, attention, memory, and emotionality. There are also simpler hypotheses that explain only individual parts of the neurobiology or phenotype of autism, such as mind-blindness (a decreased ability for theory of mind), the weak central coherence theory, or the extreme male brain and empathising–systemising theory.

Evolutionary hypotheses

Research exploring the evolutionary benefits of autism and associated genes has suggested that autistic people may have played a "unique role in technological spheres and understanding of natural systems" in the course of human development. It has been suggested that it may have arisen as "a slight trade off for other traits that are seen as highly advantageous", providing "advantages in tool making and mechanical thinking", with speculation that the condition may "reveal itself to be the result of a balanced polymorphism, like sickle cell anemia, that is advantageous in a certain mixture of genes and disadvantageous in specific combinations".

In 2011, a paper in Evolutionary Psychology proposed that autistic traits, including increased abilities for spatial intelligence, concentration and memory, could have been naturally selected to enable self-sufficient foraging in a more (although not completely) solitary environment, referred to as the "Solitary Forager Hypothesis". A 2016 paper examines Asperger syndrome as "an alternative prosocial adaptive strategy" which may have developed as a result of the emergence of "collaborative morality" in the context of small-scale hunter-gathering, i.e. where "a positive social reputation for making a contribution to group wellbeing and survival" becomes more important than complex social understanding.

Conversely, some multidisciplinary research suggests that recent human evolution may be a driving force in the rise of a number of medical conditions in recent human populations, including autism. Studies in evolutionary medicine indicate that as biological evolution becomes outpaced by cultural evolution, disorders linked to bodily dysfunction increase in prevalence due to a lack of contact with pathogens and negative environmental conditions that once widely affected ancestral populations. Because natural selection primarily favors reproduction over health and longevity, the lack of this impetus to adapt to certain harmful circumstances creates a tendency for genes in descendant populations to over-express themselves, which may cause a wide array of maladies, ranging from mental disorders to autoimmune diseases.

Pathophysiology

Autism's symptoms result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain. How autism occurs is not yet well understood. Its mechanism can be divided into two areas: the pathophysiology of brain structures and processes associated with autism, and the neuropsychological linkages between brain structures and behaviors. The behaviors appear to have multiple pathophysiologies.

There is evidence that gut–brain axis abnormalities may be involved. A 2015 review proposed that immune, gastrointestinal inflammation, malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, gut flora alterations, and food metabolites may cause brain neuroinflammation and dysfunction. A 2016 review concludes that enteric nervous system abnormalities might play a role in neurological disorders such as autism. Neural connections and the immune system are a pathway that may allow diseases originated in the intestine spread to the brain.

Several lines of evidence point to synaptic dysfunction as a cause of autism. Some rare mutations may lead to autism by disrupting some synaptic pathways, such as those involved with cell adhesion. All known teratogens (agents that cause birth defects) related to the risk of autism appear to act during the first eight weeks from conception, and though this does not exclude the possibility that autism can be initiated or affected later, there is strong evidence that autism arises very early in development.

In general, neuroanatomical studies support the concept that autism may involve a combination of brain enlargement in some areas and reduction in others. These studies suggest that autism may be caused by abnormal neuronal growth and pruning during the early stages of prenatal and postnatal brain development, leaving some areas of the brain with too many neurons and other areas with too few neurons. Some research has reported an overall brain enlargement in autism, while others suggest abnormalities in several areas of the brain, including the frontal lobe, the mirror neuron system, the limbic system, the temporal lobe, and the corpus callosum.

In functional neuroimaging studies, when performing theory of mind and facial emotion response tasks, the median person on the autism spectrum exhibits less activation in the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices of the brain than the median member of a properly sampled control population. This finding coincides with reports demonstrating abnormal patterns of cortical thickness and grey matter volume in those regions of autistic peoples' brains.

Brain connectivity

Brains of autistic individuals have been observed to have abnormal connectivity and the degree of these abnormalities directly correlates with the severity of autism. Following are some observed abnormal connectivity patterns in autistic individuals:

- Decreased connectivity between different specialized regions of the brain (e.g. lower neuron density in corpus callosum) and relative over-connectivity within specialized regions of the brain by adulthood. Connectivity between different regions of the brain ('long-range' connectivity) is important for integration and global processing of information and comparing incoming sensory information with the existing model of the world within the brain. Connections within each specialized regions ('short-range' connections) are important for processing individual details and modifying the existing model of the world within the brain to more closely reflect incoming sensory information. In infancy, children at high risk for autism that were later diagnosed with autism were observed to have abnormally high long-range connectivity which then decreased through childhood to eventual long-range under-connectivity by adulthood.

- Abnormal preferential processing of information by the left hemisphere of the brain vs. preferential processing of information by right hemisphere in neurotypical individuals. The left hemisphere is associated with processing information related to details whereas the right hemisphere is associated with processing information in a more global and integrated sense that is essential for pattern recognition. For example, visual information like face recognition is normally processed by the right hemisphere which tends to integrate all information from an incoming sensory signal, whereas an ASD brain preferentially processes visual information in the left hemisphere where information tends to be processed for local details of the face rather than the overall configuration of the face. This left lateralization negatively impacts both facial recognition and spatial skills.

- Increased functional connectivity within the left hemisphere which directly correlates with severity of autism. This observation also supports preferential processing of details of individual components of sensory information over global processing of sensory information in an ASD brain.

- Prominent abnormal connectivity in the frontal and occipital regions. In autistic individuals low connectivity in the frontal cortex was observed from infancy through adulthood. This is in contrast to long-range connectivity which is high in infancy and low in adulthood in ASD. Abnormal neural organization is also observed in the Broca's area which is important for speech production.

Neuropathology

Listed below are some characteristic findings in ASD brains on molecular and cellular levels regardless of the specific genetic variation or mutation contributing to autism in a particular individual:

- Limbic system with smaller neurons that are more densely packed together. Given that the limbic system is the main center of emotions and memory in the human brain, this observation may explain social impairment in ASD.

- Fewer and smaller Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum. New research suggest a role of the cerebellum in emotional processing and language.

- Increased number of astrocytes and microglia in the cerebral cortex. These cells provide metabolic and functional support to neurons and act as immune cells in the nervous system, respectively.

- Increased brain size in early childhood causing macrocephaly in 15–20% of ASD individuals. The brain size however normalizes by mid-childhood. This variation in brain size in not uniform in the ASD brain with some parts like the frontal and temporal lobes being larger, some like the parietal and occipital lobes being normal sized, and some like cerebellar vermis, corpus callosum, and basal ganglia being smaller than neurotypical individuals.

- Cell adhesion molecules that are essential to formation and maintenance of connections between neurons, neuroligins found on postsynaptic neurons that bind presynaptic cell adhesion molecules, and proteins that anchor cell adhesion molecules to neurons are all found to be mutated in ASD.

Gut-immune-brain axis

46% to 84% of autistic individuals have GI-related problems like reflux, diarrhea, constipation, inflammatory bowel disease, and food allergies. It has been observed that the makeup of gut bacteria in autistic people is different than that of neurotypical individuals which has raised the question of influence of gut bacteria on ASD development via inducing an inflammatory state. Listed below are some research findings on the influence of gut bacteria and abnormal immune responses on brain development:

- Some studies on rodents have shown gut bacteria influencing emotional functions and neurotransmitter balance in the brain, both of which are impacted in ASD.

- The immune system is thought to be the intermediary that modulates the influence of gut bacteria on the brain. Some ASD individuals have a dysfunctional immune system with higher numbers of some types of immune cells, biochemical messengers and modulators, and autoimmune antibodies. Increased inflammatory biomarkers correlate with increased severity of ASD symptoms and there is some evidence to support a state of chronic brain inflammation in ASD.

- More pronounced inflammatory responses to bacteria were found in ASD individuals with an abnormal gut microbiota. Additionally, immunoglobulin A antibodies that are central to gut immunity were also found in elevated levels in ASD populations. Some of these antibodies may attack proteins that support myelination of the brain, a process that is important for robust transmission of neural signal in many nerves.

- Activation of the maternal immune system during pregnancy (by gut bacteria, bacterial toxins, an infection, or non-infectious causes) and gut bacteria in the mother that induce increased levels of Th17, a pro-inflammatory immune cell, have been associated with an increased risk of autism. Some maternal IgG antibodies that cross the placenta to provide passive immunity to the fetus can also attack the fetal brain.

- It is proposed that inflammation within the brain promoted by inflammatory responses to harmful gut microbiome impacts brain development.

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IFN-α, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-17 have been shown to promote autistic behaviors in animal models. Giving anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-17 along with IL-6 and IL-17, respectively, have been shown to negate this effect in the same animal models.

- Some gut proteins and microbial products can cross the blood–brain barrier and activate mast cells in the brain. Mast cells release pro-inflammatory factors and histamine which further increase blood–brain barrier permeability and help set up a cycle of chronic inflammation.

Social brain interconnectivity

A number of discrete brain regions and networks among regions that are involved in dealing with other people have been discussed together under the rubric of the social brain. As of 2012, there is a consensus that autism spectrum is likely related to problems with interconnectivity among these regions and networks, rather than problems with any specific region or network.

Temporal lobe

Functions of the temporal lobe are related to many of the deficits observed in individuals with ASDs, such as receptive language, social cognition, joint attention, action observation, and empathy. The temporal lobe also contains the superior temporal sulcus and the fusiform face area, which may mediate facial processing. It has been argued that dysfunction in the superior temporal sulcus underlies the social deficits that characterize autism. Compared to neurotypical individuals, one study found that individuals with high-functioning autism had reduced activity in the fusiform face area when viewing pictures of faces.

Mitochondria

ASD could be linked to mitochondrial disease, a basic cellular abnormality with the potential to cause disturbances in a wide range of body systems. A 2012 meta-analysis study, as well as other population studies show that approximately 5% of autistic children meet the criteria for classical mitochondrial dysfunction. It is unclear why this mitochondrial disease occurs, considering that only 23% of children with both ASD and mitochondrial disease present with mitochondrial DNA abnormalities.

Serotonin

Serotonin is a major neurotransmitter in the nervous system and contributes to formation of new neurons (neurogenesis), formation of new connections between neurons (synaptogenesis), remodeling of synapses, and survival and migration of neurons, processes that are necessary for a developing brain and some also necessary for learning in the adult brain. 45% of ASD individuals have been found to have increased blood serotonin levels. It has been hypothesized that increased activity of serotonin in the developing brain may facilitate the onset of ASD, with an association found in six out of eight studies between the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) by the pregnant mother and the development of ASD in the child exposed to SSRI in the antenatal environment. The study could not definitively conclude SSRIs caused the increased risk for ASD due to the biases found in those studies, and the authors called for more definitive, better conducted studies. Confounding by indication has since then been shown to be likely. However, it is also hypothesized that SSRIs may help reduce symptoms of ASD and even positively affect brain development in some ASD patients.

Diagnosis

Autism spectrum disorder is a clinical diagnosis that is typically made by a physician based on reported and directly observed behavior in the affected individual. According to the updated diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5-TR, in order to receive a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, one must present with "persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction" and "restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities." These behaviors must begin in early childhood and affect one's ability to perform everyday tasks. Furthermore, the symptoms must not be fully explainable by intellectual developmental disorder or global developmental delay.

There are several factors that make autism spectrum disorder difficult to diagnose. First off, there are no standardized imaging, molecular or genetic tests that can be used to diagnose ASD. Additionally, there is a lot of variety in how ASD affects individuals. The behavioral manifestations of ASD depend on one's developmental stage, age of presentation, current support, and individual variability. Lastly, there are multiple conditions that may present similarly to autism spectrum disorder, including intellectual disability, hearing impairment, a specific language impairment such as Landau–Kleffner syndrome.ADHD, anxiety disorder, and psychotic disorders. Furthermore, the presence of autism can make it harder to diagnose coexisting psychiatric disorders such as depression.

Ideally the diagnosis of ASD should be given by a team of clinicians (e.g. pediatricians, child psychiatrists, child neurologists) based on information provided from the affected individual, caregivers, other medical professionals and from direct observation. Evaluation of a child or adult for autism spectrum disorder typically starts with a pediatrician or primary care physician taking a developmental history and performing a physical exam. If warranted, the physician may refer the individual to an ASD specialist who will observe and assess cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions. A pediatric neuropsychologist is often asked to assess behavior and cognitive skills, both to aid diagnosis and to help recommend educational interventions. Further workup may be performed after someone is diagnosed with ASD. This may include a clinical genetics evaluation particularly when other symptoms already suggest a genetic cause. Although up to 40% of ASD cases may be linked to genetic causes, it is not currently recommended to perform complete genetic testing on every individual who is diagnosed with ASD. Consensus guidelines for genetic testing in patients with ASD in the US and UK are limited to high-resolution chromosome and fragile X testing.Metabolic and neuroimaging tests are also not routinely performed for diagnosis of ASD.

The age at which ASD is diagnosed varies. Sometimes ASD can be diagnosed as early as 18 months, however, diagnosis of ASD before the age of two years may not be reliable. Diagnosis becomes increasingly stable over the first three years of life. For example, a one-year-old who meets diagnostic criteria for ASD is less likely than a three-year-old to continue to do so a few years later. Additionally, age of diagnosis may depend on the severity of ASD, with more severe forms of ASD more likely to be diagnosed at an earlier age. Issues with access to healthcare such as cost of appointments or delays in making appointments often lead to delays in the diagnosis of ASD. In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice. Lack of access to appropriate medical care, broadening diagnostic criteria and increased awareness surrounding ASD in recent years has resulted in an increased number of individuals receiving a diagnosis of ASD as adults. Diagnosis of ASD in adults poses unique challenges because it still relies on an accurate developmental history and because autistic adults sometimes learn coping strategies, known as "masking" or "camouflaging", which may make it more difficult to obtain a diagnosis.

The presentation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder may vary based on sex and gender identity. Most studies that have investigated the impact of gender on presentation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder have not differentiated between the impact of sex versus gender. There is some evidence that autistic women and girls tend to show less repetitive behavior and may engage in more camouflaging than autistic males. Camouflaging may include making oneself perform normative facial expressions and eye contact. Differences in behavioral presentation and gender-stereotypes may make it more challenging to diagnose autism spectrum disorder in a timely manner in females. A notable percentage of autistic females may be misdiagnosed, diagnosed after a considerable delay, or not diagnosed at all.

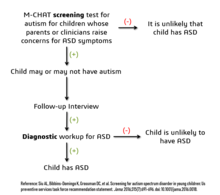

Considering the unique challenges in diagnosing ASD using behavioral and observational assessment, specific US practice parameters for its assessment were published by the American Academy of Neurology in the year 2000, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 1999, and a consensus panel with representation from various professional societies in 1999. The practice parameters outlined by these societies include an initial screening of children by general practitioners (i.e., "Level 1 screening") and for children who fail the initial screening, a comprehensive diagnostic assessment by experienced clinicians (i.e. "Level 2 evaluation"). Furthermore, it has been suggested that assessments of children with suspected ASD be evaluated within a developmental framework, include multiple informants (e.g., parents and teachers) from diverse contexts (e.g., home and school), and employ a multidisciplinary team of professionals (e.g., clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists).

As of 2019, psychologists wait until a child showed initial evidence of ASD tendencies, then administer various psychological assessment tools to assess for ASD. Among these measurements, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) are considered the "gold standards" for assessing autistic children. The ADI-R is a semi-structured parent interview that probes for symptoms of autism by evaluating a child's current behavior and developmental history. The ADOS is a semi-structured interactive evaluation of ASD symptoms that is used to measure social and communication abilities by eliciting several opportunities for spontaneous behaviors (e.g., eye contact) in standardized context. Various other questionnaires (e.g., The Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist) and tests of cognitive functioning (e.g., The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test) are typically included in an ASD assessment battery. The diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders (DISCO) may also be used.

Screening

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child's atypical behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months. If a child does not meet any of the following milestones, it "is an absolute indication to proceed with further evaluations. Delay in referral for such testing may delay early diagnosis and treatment and affect the [child's] long-term outcome."

- No response to name (or gazing with direct eye contact) by 6 months.

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

The Japanese practice is to screen all children for ASD at 18 and 24 months, using autism-specific formal screening tests. In contrast, in the UK, children whose families or doctors recognize possible signs of autism are screened. It is not known which approach is more effective. The UK National Screening Committee does not recommend universal ASD screening in young children. Their main concerns includes higher chances of misdiagnosis at younger ages and lack of evidence of effectiveness of early interventions. There is no consensus between professional and expert bodies in the US on screening for autism in children younger than 3 years.

Screening tools include the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire, and the First Year Inventory; initial data on M-CHAT and its predecessor, the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), on children aged 18–30 months suggests that it is best used in a clinical setting and that it has low sensitivity (many false-negatives) but good specificity (few false-positives). It may be more accurate to precede these tests with a broadband screener that does not distinguish ASD from other developmental disorders. Screening tools designed for one culture's norms for behaviors like eye contact may be inappropriate for a different culture. Although genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical, it can be considered in some cases, such as children with neurological symptoms and dysmorphic features.

Misdiagnosis

There is a significant level of misdiagnosis of autism in neurodevelopmentally typical children; 18–37% of children diagnosed with ASD eventually lose their diagnosis. This high rate of lost diagnosis cannot be accounted for by successful ASD treatment alone. The most common reason parents reported as the cause of lost ASD diagnosis was new information about the child (73.5%), such as a replacement diagnosis. Other reasons included a diagnosis given so the child could receive ASD treatment (24.2%), ASD treatment success or maturation (21%), and parents disagreeing with the initial diagnosis (1.9%).

Many of the children who were later found not to meet ASD diagnosis criteria then received diagnosis for another developmental disorder. Most common was ADHD, but other diagnoses included sensory disorders, anxiety, personality disorder, or learning disability. Neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorders that are commonly misdiagnosed as ASD include specific language impairment, social communication disorder, anxiety disorder, reactive attachment disorder, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, hearing loss and normal behavioral variation. Some behavioral variations that resemble autistic traits are repetitive behaviors, sensitivity to change in daily routines, focused interests, and toe-walking. These are considered normal behavioral variations when they do not cause impaired function. Boys are more likely to exhibit repetitive behaviors especially when excited, tired, bored, or stressed. Some ways of distinguishing typical behavioral variations from autistic behaviors are the ability of the child to suppress these behaviors and the absence of these behaviors during sleep.

Comorbidity

ASDs tend to be highly comorbid with other disorders.Comorbidity may increase with age and may worsen the course of youth with ASDs and make intervention and treatment more difficult. Distinguishing between ASDs and other diagnoses can be challenging because the traits of ASDs often overlap with symptoms of other disorders, and the characteristics of ASDs make traditional diagnostic procedures difficult.

- The most common medical condition occurring in individuals with ASDs is seizure disorder or epilepsy, which occurs in 11–39% of autistic individuals. The risk varies with age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.

- Tuberous sclerosis, an autosomal dominant genetic condition in which non-malignant tumors grow in the brain and on other vital organs, is present in 1–4% of individuals with ASDs.

- Intellectual disabilities are some of the most common comorbid disorders with ASDs. As diagnosis is increasingly being given to people with higher functioning autism, there is a tendency for the proportion with comorbid intellectual disability to decrease over time. In a 2019 study, it was estimated that approximately 30-40% of people diagnosed with ASD also have intellectual disability. Recent research has suggested that autistic people with intellectual disability tend to have rarer, more harmful, genetic mutations than those found in people solely diagnosed with autism. A number of genetic syndromes causing intellectual disability may also be comorbid with ASD, including fragile X, Down, Prader-Willi, Angelman, Williams syndrome,branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase kinase deficiency, and SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability.

- Learning disabilities are also highly comorbid in individuals with an ASD. Approximately 25–75% of individuals with an ASD also have some degree of a learning disability.

- Various anxiety disorders tend to co-occur with ASDs, with overall comorbidity rates of 7–84%. They are common among children with ASD; there are no firm data, but studies have reported prevalences ranging from 11% to 84%. Many anxiety disorders have symptoms that are better explained by ASD itself, or are hard to distinguish from ASD's symptoms.

- Rates of comorbid depression in individuals with an ASD range from 4–58%.

- The relationship between ASD and schizophrenia remains a controversial subject under continued investigation, and recent meta-analyses have examined genetic, environmental, infectious, and immune risk factors that may be shared between the two conditions.Oxidative stress, DNA damage and DNA repair have been postulated to play a role in the aetiopathology of both ASD and schizophrenia.

- Deficits in ASD are often linked to behavior problems, such as difficulties following directions, being cooperative, and doing things on other people's terms. Symptoms similar to those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be part of an ASD diagnosis.

- Sensory processing disorder is also comorbid with ASD, with comorbidity rates of 42–88%.

- Starting in adolescence, some people with Asperger syndrome (26% in one sample) fall under the criteria for the similar condition schizoid personality disorder, which is characterized by a lack of interest in social relationships, a tendency towards a solitary or sheltered lifestyle, secretiveness, emotional coldness, detachment and apathy. Asperger syndrome was traditionally called "schizoid disorder of childhood."

- Genetic disorders - about 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndromes.

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.

- Gastrointestinal problems are one of the most commonly co-occurring medical conditions in autistic people. These are linked to greater social impairment, irritability, language impairments, mood changes, and behavior and sleep problems.

- Sleep problems affect about two-thirds of individuals with ASD at some point in childhood. These most commonly include symptoms of insomnia such as difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Sleep problems are associated with difficult behaviors and family stress, and are often a focus of clinical attention over and above the primary ASD diagnosis.

Management

There is no treatment as such for autism, and many sources advise that this is not an appropriate goal, although treatment of co-occurring conditions remains an important goal. There is no cure for autism as of 2022, nor can any of the known treatments significantly reduce brain mutations caused by autism, although those who require little-to-no support are more likely to experience a lessening of symptoms over time. Several interventions can help children with autism, and no single treatment is best, with treatment typically tailored to the child's needs. Studies of interventions have methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy; however, the development of evidence-based interventions has advanced.

The main goals of treatment are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes. Behavioral, psychological, education, and/or skill-building interventions may be used to assist autistic people to learn life skills necessary for living independently, as well as other social, communication, and language skills. Therapy also aims to reduce challenging behaviors and build upon strengths.

Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life may help children acquire self-care, language, and job skills. Although evidence-based interventions for autistic children vary in their methods, many adopt a psychoeducational approach to enhancing cognitive, communication, and social skills while minimizing problem behaviors. While medications have not been found to help with core symptoms, they may be used for associated symptoms, such as irritability, inattention, or repetitive behavior patterns.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Intensive, sustained special education or remedial education programs and behavior therapy early in life may help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills. Available approaches include applied behavior analysis, developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy,social skills therapy, and occupational therapy. Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focus treatment on a specific area of deficit. Generally, when educating those with autism, specific tactics may be used to effectively relay information to these individuals. Using as much social interaction as possible is key in targeting the inhibition autistic individuals experience concerning person-to-person contact. Additionally, research has shown that employing semantic groupings, which involves assigning words to typical conceptual categories, can be beneficial in fostering learning.

There has been increasing attention to the development of evidence-based interventions for autistic young children. Three theoretical frameworks outlined for early childhood intervention include applied behavior analysis (ABA), the developmental social-pragmatic model (DSP) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Although ABA therapy has a strong evidence base, particularly in regard to early intensive home-based therapy, ABA's effectiveness may be limited by diagnostic severity and IQ of the person affected by ASD. The Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology has published a paper deeming two early childhood interventions "well-established": individual comprehensive ABA, and focused teacher-implemented ABA combined with DSP.

Another evidence-based intervention that has demonstrated efficacy is a parent training model, which teaches parents how to implement various ABA and DSP techniques themselves. Various DSP programs have been developed to explicitly deliver intervention systems through at-home parent implementation.

In October 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) proposed new evidence-based recommendations for early interventions in ASD for children under 3. These recommendations emphasize early involvement with both developmental and behavioral methods, support by and for parents and caregivers, and a focus on both the core and associated symptoms of ASD. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) is effective in reducing behavioral problems associated with autism in most autistic children but did help improve IQ and language skills. The Cochrane review did acknowledge that this may be due to the low quality of studies currently available on EIBI and therefore providers should recommend EIBI based on their clinical judgement and the family's preferences. No adverse effects of EIBI treatment were found. A meta-analysis in that same database indicates that due to the degrees of severity in ASD, there is variable responses to differing early ABA interventions.

Generally speaking, treatment of ASD focuses on behavioral and educational interventions to target its two core symptoms: social communication deficits and restricted, repetitive behaviors. If symptoms continue after behavioral strategies have been implemented, some medications can be recommended to target specific symptoms or co-existing problems such as restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs), anxiety, depression, hyperactivity/inattention and sleep disturbance.Melatonin for example can be used for sleep problems.

While there are a number of parent-mediated behavioral therapies to target social communication deficits in children with autism, there is uncertainty regarding the efficacy of interventions to treat RRBs.

Education

Educational interventions often used include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy and social skills therapy. Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focalize treatment on a specific area of deficit.

The quality of research for early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI)—a treatment procedure incorporating over thirty hours per week of the structured type of ABA that is carried out with very young children—is currently low, and more vigorous research designs with larger sample sizes are needed. Two theoretical frameworks outlined for early childhood intervention include structured and naturalistic ABA interventions, and developmental social pragmatic models (DSP). One interventional strategy utilizes a parent training model, which teaches parents how to implement various ABA and DSP techniques, allowing for parents to disseminate interventions themselves. Various DSP programs have been developed to explicitly deliver intervention systems through at-home parent implementation. Despite the recent development of parent training models, these interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in numerous studies, being evaluated as a probable efficacious mode of treatment.Early, intensive ABA therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing communication and adaptive functioning in preschool children; it is also well-established for improving the intellectual performance of that age group.

A 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis database concludes how some recent research is beginning to suggest that because of the heterology of ASD, there is two varying ABA teaching approaches to acquiring spoken language: children with more general expressive language delays respond sufficiently to the naturalistic approach, whereas children with receptive language delays require discrete trial training—a structured and intensive form of ABA.

Similarly, a teacher-implemented intervention that utilizes a more naturalistic form of ABA combined with a developmental social pragmatic approach has been found to be beneficial in improving social-communication skills in young children, although there is less evidence in its treatment of global symptoms. Neuropsychological reports are often poorly communicated to educators, resulting in a gap between what a report recommends and what education is provided. The appropriateness of including children with varying severity of autism spectrum disorders in the general education population is a subject of current debate among educators and researchers.

Pharmacological interventions

Medications may be used to treat ASD symptoms that interfere with integrating a child into home or school when behavioral treatment fails. They may also be used for associated health problems, such as ADHD or anxiety. However, their routine prescription for the core features of ASD is not recommended. More than half of US children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics. The atypical antipsychotic drugs risperidone and aripiprazole are FDA-approved for treating associated aggressive and self-injurious behaviors. However, their side effects must be weighed against their potential benefits, and autistic people may respond atypically. Side effects may include weight gain, tiredness, drooling, and aggression. There is some emerging data that show positive effects of aripiprazole and risperidone on restricted and repetitive behaviors (i.e., stimming; e.g., flapping, twisting, complex whole-body movements), but due to the small sample size and different focus of these studies and the concerns about its side effects, antipsychotics are not recommended as primary treatment of RRBs.SSRI antidepressants, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, have been shown to be effective in reducing repetitive and ritualistic behaviors, while the stimulant medication methylphenidate is beneficial for some children with co-morbid inattentiveness or hyperactivity. There is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD. No known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.

Alternative medicine

A multitude of researched alternative therapies have also been implemented. Many have resulted in harm to autistic people. A 2020 systematic review on adults with autism has provided emerging evidence for decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression through mindfulness-based interventions for improving mental health.

Although popularly used as an alternative treatment for autistic people, as of 2018 there is no good evidence to recommend a gluten- and casein-free diet as a standard treatment. A 2018 review concluded that it may be a therapeutic option for specific groups of children with autism, such as those with known food intolerances or allergies, or with food intolerance markers. The authors analyzed the prospective trials conducted to date that studied the efficacy of the gluten- and casein-free diet in children with ASD (4 in total). All of them compared gluten- and casein-free diet versus normal diet with a control group (2 double-blind randomized controlled trials, 1 double-blind crossover trial, 1 single-blind trial). In two of the studies, whose duration was 12 and 24 months, a significant improvement in ASD symptoms (efficacy rate 50%) was identified. In the other two studies, whose duration was 3 months, no significant effect was observed. The authors concluded that a longer duration of the diet may be necessary to achieve the improvement of the ASD symptoms. Other problems documented in the trials carried out include transgressions of the diet, small sample size, the heterogeneity of the participants and the possibility of a placebo effect. In the subset of people who have gluten sensitivity there is limited evidence that suggests that a gluten-free diet may improve some autistic behaviors.