Pattern hair loss

| Pattern hair loss | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Male pattern baldness; Female pattern baldness; Androgenic alopecia; Androgenetic alopecia; alopecia androgenetica |

| |

| Male-pattern hair loss shown on the vertex of the scalp | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, plastic surgery |

Pattern hair loss (also known as androgenetic alopecia (AGA)) is a hair loss condition that primarily affects the top and front of the scalp. In male-pattern hair loss (MPHL), the hair loss typically presents itself as either a receding front hairline, loss of hair on the crown (vertex) of the scalp, or a combination of both. Female-pattern hair loss (FPHL) typically presents as a diffuse thinning of the hair across the entire scalp.

Male pattern hair loss seems to be due to a combination of oxidative stress, the microbiome of the scalp, genetics, and circulating androgens; particularly dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Men with early onset androgenic alopecia (before the age of 35) have been deemed the male phenotypic equivalent for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). As an early clinical expression of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, AGA is related to being an increased risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, glucose metabolism disorders,type 2 diabetes, and enlargement of the prostate.

The cause in female pattern hair loss remains unclear; androgenetic alopecia for women is associated with an increased risk of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Management may include simply accepting the condition or shaving one's head to improve the aesthetic aspect of the condition. Otherwise, common medical treatments include minoxidil, finasteride, dutasteride, or hair transplant surgery. Use of finasteride and dutasteride in women is not well-studied and may result in birth defects if taken during pregnancy.

Pattern hair loss by the age of 50 affects about half of males and a quarter of females. It is the most common cause of hair loss. Both males aged 40–91 and younger male patients of early onset AGA (before the age of 35), had a higher likelihood of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and insulin resistance. With younger males, studies found metabolic syndrome to be at approximately a 4× increased frequency which is clinically deemed significant. Abdominal obesity, hypertension and lowered high density lipoprotein were also significantly higher for younger groups.

Signs and symptoms

Pattern hair loss is classified as a form of non-scarring hair loss.

Male-pattern hair loss begins above the temples and at the vertex (calvaria) of the scalp. As it progresses, a rim of hair at the sides and rear of the head remains. This has been referred to as a "Hippocratic wreath", and rarely progresses to complete baldness.

Female-pattern hair loss more often causes diffuse thinning without hairline recession; similar to its male counterpart, female androgenic alopecia rarely leads to total hair loss. The Ludwig scale grades severity of female-pattern hair loss. These include Grades 1, 2, 3 of balding in women based on their scalp showing in the front due to thinning of hair.

In most cases, receding hairline is the first starting point; the hairline starts moving backwards from the front of the head and the sides.

Causes

Hormones and genes

KRT37 is the only keratin that is regulated by androgens. This sensitivity to androgens was acquired by Homo sapiens and is not shared with their great ape cousins. Although Winter et al. found that KRT37 is expressed in all the hair follices of chimpanzees, it was not detected in the head hair of modern humans. As androgens are known to grow hair on the body, but decrease it on the scalp, this lack of scalp KRT37 may help explain the paradoxical nature of Androgenic alopecia as well as the fact that head hair anagen cycles are extremely long.

The initial programming of pilosebaceous units of hair follicles begins in utero. The physiology is primarily androgenic, with dihydrotestosterone (DHT) being the major contributor at the dermal papillae. Men with premature androgenic alopecia tend to have lower than normal values of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), testosterone, and epitestosterone when compared to men without pattern hair loss. Although hair follicles were previously thought to be permanently gone in areas of complete hair loss, they are more likely dormant, as recent studies have shown the scalp contains the stem cell progenitor cells from which the follicles arose.

Transgenic studies have shown that growth and dormancy of hair follicles are related to the activity of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) at the dermal papillae, which is affected by DHT. Androgens are important in male sexual development around birth and at puberty. They regulate sebaceous glands, apocrine hair growth, and libido. With increasing age, androgens stimulate hair growth on the face, but can suppress it at the temples and scalp vertex, a condition that has been referred to as the 'androgen paradox'.

Men with androgenic alopecia typically have higher 5α-reductase, higher total testosterone, higher unbound/free testosterone, and higher free androgens, including DHT. 5-alpha-reductase converts free testosterone into DHT, and is highest in the scalp and prostate gland. DHT is most commonly formed at the tissue level by 5α-reduction of testosterone. The genetic corollary that codes for this enzyme has been discovered.Prolactin has also been suggested to have different effects on the hair follicle across gender.

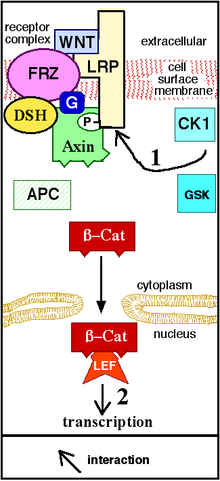

Also, crosstalk occurs between androgens and the Wnt-beta-catenin signaling pathway that leads to hair loss. At the level of the somatic stem cell, androgens promote differentiation of facial hair dermal papillae, but inhibit it at the scalp. Other research suggests the enzyme prostaglandin D2 synthase and its product prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) in hair follicles as contributive.

These observations have led to study at the level of the mesenchymal dermal papillae.Types 1 and 2 5α reductase enzymes are present at pilosebaceous units in papillae of individual hair follicles. They catalyze formation of the androgen dihydrotestosterone from testosterone, which in turn regulate hair growth. Androgens have different effects at different follicles: they stimulate IGF-1 at facial hair, leading to growth, but can also stimulate TGF β1, TGF β2, dickkopf1, and IL-6 at the scalp, leading to catagenic miniaturization. Hair follicles in anaphase express four different caspases. Significant levels of inflammatory infiltrate have been found in transitional hair follicles. Interleukin 1 is suspected to be a cytokine mediator that promotes hair loss.

The fact that hair loss is cumulative with age while androgen levels fall as well as the fact that finasteride does not reverse advanced stages of androgenetic alopecia remains a mystery, but possible explanations are higher conversion of testosterone to DHT locally with age as higher levels of 5-alpha reductase are noted in balding scalp, and higher levels of DNA damage in the dermal papilla as well as senescence of the dermal papilla due to androgen receptor activation and environmental stress. The mechanism by which the androgen receptor triggers dermal papilla permanent senescence is not known, but may involve IL6, TGFB-1 and oxidative stress. Senescence of the dermal papilla is measured by lack of mobility, different size and shape, lower replication and altered output of molecules and different expression of markers. The dermal papilla is the primary location of androgen action and its migration towards the hair bulge and subsequent signaling and size increase are required to maintain the hair follicle so senescence via the androgen receptor explains much of the physiology.

Inheritance

Male pattern baldness is a complex genetic condition with "particularly strong signals on the X chromosome".

Metabolic syndrome

Multiple cross-sectional studies have found associations between early androgenic alopecia, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome, with low HDL being the component of metabolic syndrome with highest association. Linolenic and linoleic acids, two major dietary sources of HDL, are 5 alpha reductase inhibitors. Premature androgenic alopecia and insulin resistance may be a clinical constellation that represents the male homologue, or phenotype, of polycystic ovary syndrome. Others have found a higher rate of hyperinsulinemia in family members of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. With early-onset AGA having an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, poorer metabolic profiles are noticed in those with AGA, including metrics for body mass index, waist circumference, fasting glucose, blood lipids, and blood pressure.

In support of the association, finasteride improves glucose metabolism and decreases glycated hemoglobin HbA1c, a surrogate marker for diabetes mellitus. The low SHBG seen with premature androgenic alopecia is also associated with, and likely contributory to, insulin resistance, and for which it still is used as an assay for pediatric diabetes mellitus.

Obesity leads to upregulation of insulin production and decrease in SHBG. Further reinforcing the relationship, SHBG is downregulated by insulin in vitro, although SHBG levels do not appear to affect insulin production.In vivo, insulin stimulates both testosterone production and SHBG inhibition in normal and obese men. The relationship between SHBG and insulin resistance has been known for some time; decades prior, ratios of SHBG and adiponectin were used before glucose to predict insulin resistance. Patients with Laron syndrome, with resultant deficient IGF, demonstrate varying degrees of alopecia and structural defects in hair follicles when examined microscopically.

Because of its association with metabolic syndrome and altered glucose metabolism, both men and women with early androgenic hair loss should be screened for impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus II. Measurement of subcutaneous and visceral adipose stores by MRI, demonstrated inverse association between visceral adipose tissue and testosterone/DHT, while subcutaneous adipose correlated negatively with SHBG and positively with estrogen. SHBG association with fasting blood glucose is most dependent on intrahepatic fat, which can be measured by MRI in and out of phase imaging sequences. Serum indices of hepatic function and surrogate markers for diabetes, previously used, show less correlation with SHBG by comparison.

Female patients with mineralocorticoid resistance present with androgenic alopecia.

IGF levels have been found lower in those with metabolic syndrome. Circulating serum levels of IGF-1 are increased with vertex balding, although this study did not look at mRNA expression at the follicle itself. Locally, IGF is mitogenic at the dermal papillae and promotes elongation of hair follicles. The major site of production of IGF is the liver, although local mRNA expression at hair follicles correlates with increase in hair growth. IGF release is stimulated by growth hormone (GH). Methods of increasing IGF include exercise, hypoglycemia, low fatty acids, deep sleep (stage IV REM), estrogens, and consumption of amino acids such as arginine and leucine. Obesity and hyperglycemia inhibit its release. IGF also circulates in the blood bound to a large protein whose production is also dependent on GH. GH release is dependent on normal thyroid hormone. During the sixth decade of life, GH decreases in production. Because growth hormone is pulsatile and peaks during sleep, serum IGF is used as an index of overall growth hormone secretion. The surge of androgens at puberty drives an accompanying surge in growth hormone.

Age

A number of hormonal changes occur with aging:

- Decrease in testosterone

- Decrease in serum DHT and 5-alpha reductase

- Decrease 3AAG, a peripheral marker of DHT metabolism

- Increase in SHBG

- Decrease in androgen receptors, 5-alpha reductase type I and II activity, and aromatase in the scalp

This decrease in androgens and androgen receptors, and the increase in SHBG are opposite the increase in androgenic alopecia with aging. This is not intuitive, as testosterone and its peripheral metabolite, DHT, accelerate hair loss, and SHBG is thought to be protective. The ratio of T/SHBG, DHT/SHBG decreases by as much as 80% by age 80, in numeric parallel to hair loss, and approximates the pharmacology of antiandrogens such as finasteride.

Free testosterone decreases in men by age 80 to levels double that of a woman at age 20. About 30% of normal male testosterone level, the approximate level in females, is not enough to induce alopecia; 60%, closer to the amount found in elderly men, is sufficient. The testicular secretion of testosterone perhaps "sets the stage" for androgenic alopecia as a multifactorial diathesis stress model, related to hormonal predisposition, environment, and age. Supplementing eunuchs with testosterone during their second decade, for example, causes slow progression of androgenic alopecia over many years, while testosterone late in life causes rapid hair loss within a month.

An example of premature age effect is Werner's syndrome, a condition of accelerated aging from low-fidelity copying of mRNA. Affected children display premature androgenic alopecia.

Permanent hair-loss is a result of reduction of the number of living hair matrixes. Long-term of insufficiency of nutrition is an important cause for the death of hair matrixes. Misrepair-accumulation aging theory suggests that dermal fibrosis is associated with the progressive hair-loss and hair-whitening in old people. With age, the dermal layer of the skin has progressive deposition of collagen fibers, and this is a result of accumulation of Misrepairs of derma. Fibrosis makes the derma stiff and makes the tissue have increased resistance to the walls of blood vessels. The tissue resistance to arteries will lead to the reduction of blood supply to the local tissue including the papillas. Dermal fibrosis is progressive; thus the insufficiency of nutrition to papillas is permanent. Senile hair-loss and hair-whitening are partially a consequence of the fibrosis of the skin.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of androgenic alopecia can be usually established based on clinical presentation in men. In women, the diagnosis usually requires more complex diagnostic evaluation. Further evaluation of the differential requires exclusion of other causes of hair loss, and assessing for the typical progressive hair loss pattern of androgenic alopecia.Trichoscopy can be used for further evaluation. Biopsy may be needed to exclude other causes of hair loss, and histology would demonstrate perifollicular fibrosis. The Hamilton–Norwood scale has been developed to grade androgenic alopecia in males by severity.

Treatment

Androgen-dependent

Finasteride is a medication of the 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) class. By inhibiting type II 5-AR, finasteride prevents the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone in various tissues including the scalp. Increased hair on the scalp can be seen within three months of starting finasteride treatment and longer-term studies have demonstrated increased hair on the scalp at 24 and 48 months with continued use. Treatment with finasteride more effectively treats male-pattern hair loss at the crown than male-pattern hair loss at the front of the head and temples.

Dutasteride is a medication in the same class as finasteride but inhibits both type I and type II 5-alpha reductase. Dutasteride is approved for the treatment of male-pattern hair loss in Korea and Japan, but not in the United States. However, it is commonly used off-label to treat male-pattern hair loss.

Androgen-independent

Minoxidil dilates small blood vessels; it is not clear how this causes hair to grow. Other treatments include tretinoin combined with minoxidil, ketoconazole shampoo, dermarolling (Collagen induction therapy), spironolactone,alfatradiol, topilutamide (fluridil), topical melatonin, and intradermal and intramuscular botulinum toxin injections to the scalp.

Female pattern

There is evidence supporting the use of minoxidil as a safe and effective treatment for female pattern hair loss, and there is no significant difference in efficiency between 2% and 5% formulations. Finasteride was shown to be no more effective than placebo based on low-quality studies. The effectiveness of laser-based therapies is unclear.Bicalutamide, an antiandrogen, is another option for the treatment of female pattern hair loss.

Procedures

More advanced cases may be resistant or unresponsive to medical therapy and require hair transplantation. Naturally occurring units of one to four hairs, called follicular units, are excised and moved to areas of hair restoration. These follicular units are surgically implanted in the scalp in close proximity and in large numbers. The grafts are obtained from either follicular unit transplantation (FUT) or follicular unit extraction (FUE). In the former, a strip of skin with follicular units is extracted and dissected into individual follicular unit grafts, and in the latter individual hairs are extracted manually or robotically. The surgeon then implants the grafts into small incisions, called recipient sites. Cosmetic scalp tattoos can also mimic the appearance of a short, buzzed haircut.

Alternative therapies

Many people use unproven treatments. Regarding female pattern alopecia, there is no evidence for vitamins, minerals, or other dietary supplements. As of 2008, there is little evidence to support the use of lasers to treat male-pattern hair loss. The same applies to special lights. Dietary supplements are not typically recommended. A 2015 review found a growing number of papers in which plant extracts were studied but only one randomized controlled clinical trial, namely a study in 10 people of saw palmetto extract.

Prognosis

Androgenic alopecia is typically experienced as a "moderately stressful condition that diminishes body image satisfaction". However, although most men regard baldness as an unwanted and distressing experience, they usually are able to cope and retain integrity of personality.

Although baldness is not as common in women as in men, the psychological effects of hair loss tend to be much greater. Typically, the frontal hairline is preserved, but the density of hair is decreased on all areas of the scalp. Previously, it was believed to be caused by testosterone just as in male baldness, but most women who lose hair have normal testosterone levels.

Epidemiology

Female androgenic alopecia has become a growing problem that, according to the American Academy of Dermatology, affects around 30 million women in the United States. Although hair loss in females normally occurs after the age of 50 or even later when it does not follow events like pregnancy, chronic illness, crash diets, and stress among others, it is now occurring at earlier ages with reported cases in women as young as 15 or 16.

For male androgenic alopecia, by the age of 50 30-50% of men have it, hereditarily there is an 80% predisposition. Notably, the link between androgenetic alopecia and metabolic syndrome is strongest in non-obese men.

Society and culture

Studies have been inconsistent across cultures regarding how balding men rate on the attraction scale. While a 2001 South Korean study showed that most people rated balding men as less attractive, a 2002 survey of Welsh women found that they rated bald and gray-haired men quite desirable. One of the proposed social theories for male pattern hair loss is that men who embraced complete baldness by shaving their heads subsequently signaled dominance, high social status, and/or longevity.

Biologists have hypothesized the larger sunlight-exposed area would allow more vitamin D to be synthesized, which might have been a "finely tuned mechanism to prevent prostate cancer" as the malignancy itself is also associated with higher levels of DHT.

Myths

Many myths exist regarding the possible causes of baldness and its relationship with one's virility, intelligence, ethnicity, job, social class, wealth, and many other characteristics.

Weight training and other types of physical activity cause baldness

Because it increases testosterone levels, many Internet forums have put forward the idea that weight training and other forms of exercise increase hair loss in predisposed individuals. Although scientific studies do support a correlation between exercise and testosterone, no direct study has found a link between exercise and baldness. However, a few have found a relationship between a sedentary life and baldness, suggesting exercise is causally relevant. The type or quantity of exercise may influence hair loss. Testosterone levels are not a good marker of baldness, and many studies actually show paradoxical low testosterone in balding persons, although research on the implications is limited.

Baldness can be caused by emotional stress, sleep deprivation, etc.

Emotional stress has been shown to accelerate baldness in genetically susceptible individuals. Stress due to sleep deprivation in military recruits lowered testosterone levels, but is not noted to have affected SHBG. Thus, stress due to sleep deprivation in fit males is unlikely to elevate DHT, which is one cause of male pattern baldness. Whether sleep deprivation can cause hair loss by some other mechanism is not clear.

Bald men are more 'virile' or sexually active than others

Levels of free testosterone are strongly linked to libido and DHT levels, but unless free testosterone is virtually nonexistent, levels have not been shown to affect virility. Men with androgenic alopecia are more likely to have a higher baseline of free androgens. However, sexual activity is multifactoral, and androgenic profile is not the only determining factor in baldness. Additionally, because hair loss is progressive and free testosterone declines with age, a male's hairline may be more indicative of his past than his present disposition.

Frequent ejaculation causes baldness

Many misconceptions exist about what can help prevent hair loss, one of these being that lack of sexual activity will automatically prevent hair loss. While a proven direct correlation exists between increased frequency of ejaculation and increased levels of DHT, as shown in a recent study by Harvard Medical School, the study suggests that ejaculation frequency may be a sign, rather than a cause, of higher DHT levels. Another study shows that although sexual arousal and masturbation-induced orgasm increase testosterone concentration around orgasm, they reduce testosterone concentration on average, and because about 5% of testosterone is converted to DHT, ejaculation does not elevate DHT levels.

The only published study to test correlation between ejaculation frequency and baldness was probably large enough to detect an association (1,390 subjects) and found no correlation, although persons with only vertex androgenetic alopecia had fewer female sexual partners than those of other androgenetic alopecia categories (such as frontal or both frontal and vertex). One study may not be enough, especially in baldness, where there is a complex with age.

Other animals

Animal models of androgenic alopecia occur naturally and have been developed in transgenic mice;chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes); bald uakaris (Cacajao rubicundus); and stump-tailed macaques (Macaca speciosa and M. arctoides). Of these, macaques have demonstrated the greatest incidence and most prominent degrees of hair loss.

Baldness is not a trait unique to human beings. One possible case study is about a maneless male lion in the Tsavo area. The Tsavo lion prides are unique in that they frequently have only a single male lion with usually seven or eight adult females, as opposed to four females in other lion prides. Male lions may have heightened levels of testosterone, which could explain their reputation for aggression and dominance, indicating that lack of mane may at one time have had an alpha correlation.

Although primates do not go bald, their hairlines do undergo recession. In infancy the hairline starts at the top of the supraorbital ridge, but slowly recedes after puberty to create the appearance of a small forehead.

External links

- NLM- Genetics Home Reference

- Scow DT, Nolte RS, Shaughnessy AF (April 1999). "Medical treatments for balding in men". American Family Physician. 59 (8): 2189–94, 2196. PMID 10221304.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

Diseases of the skin and appendages by morphology

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growths |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rashes |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous disorders |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Disorders of skin appendages

| |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nail |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Hair |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Sweat glands |

|

||||||||||||||||||