Elephant

| Elephants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

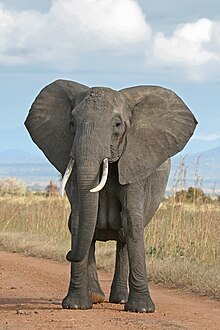

| A female African bush elephant in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

|

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | Elephantoidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Groups included | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of living elephant species | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

| |

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae and the order Proboscidea. The order was formerly much more diverse during the Pleistocene, but most species became extinct during the Late Pleistocene epoch. Distinctive features of elephants include a long proboscis called a trunk, tusks, large ear flaps, pillar-like legs, and tough but sensitive skin. The trunk is used for breathing and is prehensile, bringing food and water to the mouth, and grasping objects. Tusks, which are derived from the incisor teeth, serve both as weapons and as tools for moving objects and digging. The large ear flaps assist in maintaining a constant body temperature as well as in communication. African elephants have larger ears and concave backs, whereas Asian elephants have smaller ears, and convex or level backs.

Elephants are scattered throughout sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia and are found in different habitats, including savannahs, forests, deserts, and marshes. They are herbivorous, and they stay near water when it is accessible. They are considered to be keystone species, due to their impact on their environments. Elephants have a fission–fusion society, in which multiple family groups come together to socialise. Females (cows) tend to live in family groups, which can consist of one female with her calves or several related females with offspring. The groups, which do not include adult males, are usually led by the oldest cow, known as the matriarch.

Males (bulls) leave their family groups when they reach puberty and may live alone or with other males. Adult bulls mostly interact with family groups when looking for a mate. They enter a state of increased testosterone and aggression known as musth, which helps them gain dominance over other males as well as reproductive success. Calves are the centre of attention in their family groups and rely on their mothers for as long as three years. Elephants can live up to 70 years in the wild. They communicate by touch, sight, smell, and sound; elephants use infrasound and seismic communication over long distances. Elephant intelligence has been compared with that of primates and cetaceans. They appear to have self-awareness, and appear to show empathy for dying and dead individuals of their kind.

African bush elephants and Asian elephants are listed as endangered and African forest elephants as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). One of the biggest threats to elephant populations is the ivory trade, as the animals are poached for their ivory tusks. Other threats to wild elephants include habitat destruction and conflicts with local people. Elephants are used as working animals in Asia. In the past, they were used in war; today, they are often controversially put on display in zoos, or exploited for entertainment in circuses. Elephants have an iconic status in human culture and have been featured in art, folklore, religion, literature, and popular culture.

Etymology

The word "elephant" is based on the Latin elephas (genitive elephantis) ("elephant"), which is the Latinised form of the Greek ἐλέφας (elephas) (genitive ἐλέφαντος (elephantos), probably from a non-Indo-European language, likely Phoenician. It is attested in Mycenaean Greek as e-re-pa (genitive e-re-pa-to) in Linear B syllabic script. As in Mycenaean Greek, Homer used the Greek word to mean ivory, but after the time of Herodotus, it also referred to the animal. The word "elephant" appears in Middle English as olyfaunt (c. 1300) and was borrowed from Old French oliphant (12th century).

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A cladogram of the elephants within Afrotheria based on molecular evidence |

Elephants belong to the family Elephantidae, the sole remaining family within the order Proboscidea. Their closest extant relatives are the sirenians (dugongs and manatees) and the hyraxes, with which they share the clade Paenungulata within the superorder Afrotheria. Elephants and sirenians are further grouped in the clade Tethytheria.

Three species of living elephants are recognised; the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).African elephants were traditionally considered a single species, Loxodonta africana, but molecular studies have affirmed their status as separate species.Mammoths (Mammuthus) are nested within living elephants as they are more closely related to Asian elephants than to African elephants. Another extinct genus of elephant, Palaeoloxodon, is also recognised, which appears to have close affinities with and to have hybridised with African elephants.

Evolution

Over 180 extinct members of order Proboscidea have been described. The earliest proboscids, the African Eritherium and Phosphatherium of the late Paleocene, heralded the first radiation. The Eocene included Numidotherium, Moeritherium and Barytherium from Africa. These animals were relatively small and some, like Moeritherium and Barytherium were probably amphibious. Later on, genera such as Phiomia and Palaeomastodon arose; the latter likely inhabited more forested areas. Proboscidean diversification changed little during the Oligocene. One notable species of this epoch was Eritreum melakeghebrekristosi of the Horn of Africa, which may have been an ancestor to several later species.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proboscidea phylogeny based on morphological and DNA evidence |

A major event in proboscidean evolution was the collision of Afro-Arabia with Eurasia, during the Early Miocene, around 18-19 million years ago allowing proboscideans to disperse from their African homeland across Eurasia, and later, around 16-15 million years ago into North America across the Bering Land Bridge. Proboscidean groups prominent during the Miocene include the deinotheres, along with the more advanced elephantimorphs, including mammutids (mastodons), gomphotheres, amebelodontids (which includes the "shovel tuskers" like Platybelodon), choerolophodontids and stegodontids. Around 10 million years ago, the earliest members of the family Elephantidae emerged in Africa, having originated from gomphotheres. Elephantids are distinguished from earlier proboscideans by a major shift in the molar morphology to parallel lophs rather than the cusps of earlier proboscideans, allowing them to become higher crowned (hypsodont) and more efficient in consuming grass. The Late Miocene saw major climactic changes, which resulted in the decline and extinction of many proboscidean groups. The earliest members of modern genera of Elephantidae appeared during the latest Miocene-early Pliocene around 5 million years ago. The elephantid genera Elephas (which includes the living Asian elephant) and Mammuthus (mammoths) migrated out of Africa during the late Pliocene, around 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago.

Over the course of the Early Pleistocene, all non-elephantid probobscidean genera outside of the Americas became extinct with the exception of Stegodon, with gomphotheres dispersing into South America as part of the Great American interchange, and mammoths migrating into North America around 1.5 million years ago. At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago the elephantid genus Palaeoloxodon dispersed outside of Africa, becoming widely distributed in Eurasia. Proboscideans underwent a dramatic decline during the Late Pleistocene, with all remaining non-elephantid proboscideans (including Stegodon, mastodons, and the gomphotheres Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon) and Palaeoloxodon becoming extinct, with mammoths only surviving in relict populations on islands around the Bering Strait into the Holocene, with their latest survival being on Wrangel Island around 4,000 years ago.

Living species

| Name | Size | Appearance | Distribution | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Male:304–336 cm (10 ft 0 in – 11 ft 0 in) (shoulder height), 5.2–6.9 t (5.7–7.6 short tons) (weight); Female: 247–273 cm (8 ft 1 in – 8 ft 11 in) (shoulder height), 2.6–3.5 t (2.9–3.9 short tons) (weight) | Relatively large and triangular ears, concave back, diamond shaped molar ridges, wrinkled skin, sloping abdomen, and two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk. | Sub-Saharan Africa; forests, savannahs, deserts, wetlands, and near lakes |

|

| African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) | 209–231 cm (6 ft 10 in – 7 ft 7 in) (shoulder height), 1.7–2.3 t (1.9–2.5 short tons) (weight); | Similar to the bush species, but with smaller and more rounded ears and thinner and straighter tusks. | West and Central Africa; equatorial forests, but occasionally gallery forests and forest/grassland ecotones. |

|

| Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Male: 261–289 cm (8 ft 7 in – 9 ft 6 in) (shoulder height), 3.5–4.6 t (3.9–5.1 short tons) (weight); Female: 228–252 cm (7 ft 6 in – 8 ft 3 in) (shoulder height), 2.3–3.1 t (2.5–3.4 short tons) (weight) | Relatively small ears, convex or level back, bumpy head, narrow molar ridges, smooth skin with some blotches of depigmentation, a straightened or saggy abdomen, and one extension at the tip of the trunk. | South and Southeast Asia; habitats with a mix of grasses, low woody plants, and trees, including dry thorn-scrub forests in southern India and Sri Lanka and evergreen forests in Malaya. |

|

Anatomy

Elephants are the largest living terrestrial animals. The skeleton is made up of 326–351 bones. The vertebrae are connected by tight joints, which limit the backbone's flexibility. African elephants have 21 pairs of ribs, while Asian elephants have 19 or 20 pairs. The skull contains air cavities (sinuses) that reduce the weight of the skull while maintaining overall strength. These cavities give the inside of the skull a honeycomb-like appearance. By contrast, the lower jaw is dense. The cranium is particularly large and provides enough room for the attachment of muscles to support the entire head. The skull is build to withstand great stress, particularly when fighting or when using the tusks. The brain is surrounded by arches in the skull which serve as protection. Because of the size of the head, the neck is relatively short to provide better support. Elephants are homeotherms, and maintain their average body temperature at ~ 36 °C, with minimum 35.2 °C during cool season, and maximum 38.0 °C during hot dry season.

Ears and eyes

Elephant ears have thick bases with thin tips. The ear flaps, or pinnae, contain numerous blood vessels called capillaries. Warm blood flows into the capillaries, helping to release excess body heat into the environment. This occurs when the pinnae are still, and the animal can enhance the effect by flapping them. Larger ear surfaces contain more capillaries, and more heat can be released. Of all the elephants, African bush elephants live in the hottest climates, and have the largest ear flaps. Elephants are capable of hearing at low frequencies and are most sensitive at 1 kHz (in close proximity to the Soprano C).

Lacking a lacrimal apparatus, the eye relies on the harderian gland to keep it moist. A durable nictitating membrane protects the eye globe. The animal's field of vision is compromised by the location and limited mobility of the eyes. Elephants are considered dichromats and they can see well in dim light but not in bright light.

Trunk

The trunk, or proboscis, is a fusion of the nose and upper lip, although in early fetal life, the upper lip and trunk are separated. The trunk is elongated and specialised to become the elephant's most important and versatile appendage. It contains up to 150,000 separate muscle fascicles, with no bone and little fat. These paired muscles consist of two major types: superficial (surface) and internal. The former are divided into dorsals, ventrals, and laterals while the latter are divided into transverse and radiating muscles. The muscles of the trunk connect to a bony opening in the skull. The nasal septum is consists of small elastic muscles between the nostrils which are divided by cartilage at the base. A unique proboscis nerve – formed by the maxillary and facial nerves – runs along both sides of the trunk. The animal's sense of smell may be four times greater than a bloodhound's.

As a muscular hydrostat, the trunk moves by precisely coordinated muscle contractions. The muscles work both with and against each other. The trunk's extreme flexibility allows it to forage and wrestle other elephants with it. It is powerful enough to lift up to 350 kg (770 lb), but also has the precision to crack a peanut shell without breaking the seed. With its trunk, an elephant can reach items up to 7 m (23 ft) high and dig for water in the mud or sand below. It also uses it to clean itself. Individuals may show lateral preference when grasping with their trunks: some prefer to twist them to the left, others to the right.

Elephants are capable of dilating their nostrils at a radius of nearly 30%, increasing the nasal volume by 64%, and can inhale at over 150 m/s (490 ft/s) which is around 30 times the speed of a human sneeze. Elephants can suck up food and water both to spray in the mouth and, in the case of the latter, to sprinkle on their bodies. The trunk of an adult Asian elephant is capable of retaining 8.5 L (2.2 US gal) of water. They will also spray dust or grass on themselves. When underwater, the elephant uses its trunk as a snorkel.

The African elephant has two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk that allow it to grasp food. The Asian elephant has only one and relies more on wrapping around a food item. Asian elephant trunks have better motor coordination. Losing the trunk would be detrimental to an elephant's survival, although in rare cases, individuals have survived with shortened ones. One trunkless elephant has been observed to graze using its lips with its hind legs in the air and balancing on its front knees.Floppy trunk syndrome is a condition of trunk paralysis in African bush elephants caused by the degradation of the peripheral nerves and muscles beginning at the tip.

Teeth

Elephants usually have 26 teeth: the incisors, known as the tusks, 12 deciduous premolars, and 12 molars. Unlike most mammals, teeth are not replaced by new ones emerging from the jaws vertically. Instead, new teeth start the back of the mouth and push out the old ones. The first chewing tooth on each side of the jaw falls out when the elephant is two to three years old. The second set of chewing teeth falls out at four to six years old. The third set falls out at 9–15 years of age and set four lasts until 18–28 years of age. The fifth set of teeth falls out at the early 40s. The sixth (and usually final) set must last the elephant the rest of its life. Elephant teeth have loop-shaped dental ridges, which are more diamond-shaped in African elephants.

Tusks

The tusks of an elephant are modified second incisors in the upper jaw. They replace deciduous milk teeth at 6–12 months of age and keep growing at about 17 cm (7 in) a year. As the tusk develops, it is topped with smooth cone-shaped enamel that eventually wanes. The dentine is known as ivory and has a cross-section of intersecting lines, known as "engine turning", which create diamond-shaped patterns. Being living tissue, a tusks are fairly soft; about as dense as the mineral calcite. The tusk protrudes from a socket in the skull and most of it is external. At least one-third of the tusk contains the pulp and some have nerves stretch even further. Thus it would be difficult to remove it without harming the animal. When removed, ivory will dry up and crack if not kept cool and wet. Tusks function in digging, debarking, marking, moving objects and fighting.

Elephants are usually right- or left-tusked, similar to humans, who are typically right- or left-handed. The dominant or "master" tusk, is typically more worn down, as it is shorter and blunter. For the African elephants, tusks are present in both males and females, and are around the same length in both sexes, reaching up to 300 cm (9 ft 10 in), but those of males tend to be more massive. In the Asian species, only the males have large tusks. Female Asians have very small tusks, or none at all. Tuskless males exist and are particularly common among Sri Lankan elephants. Asian males can have tusks as long as Africans', but they are usually slimmer and lighter; the largest recorded was 302 cm (9 ft 11 in) long and weighed 39 kg (86 lb). Hunting for elephant ivory in Africa and Asia has led to natural selection for shorter tusks and tusklessness.

Skin

An elephant's skin is generally very tough, at 2.5 cm (1 in) thick on the back and parts of the head. The skin around the mouth, anus, and inside of the ear is considerably thinner. Elephants are typically grey, but African elephants look brown or reddish after rolling in coloured mud. Asian elephants have some patches of depigmentation, particularly on the head. Calves have brownish or reddish hair, with the head and back being particularly hairy. As elephants mature, their hair darkens and becomes sparser, but dense concentrations of hair and bristles remain on the tip of the tail and parts of the head and genitals. Normally the skin of an Asian elephant is covered with more hair than its African counterpart. Their hair is thought to be for thermoregulation, helping them lose heat in their hot environments.

Although tough, an elephant's skin is very sensitive and requires mud baths to maintain moisture and protect it from burning and insect bites. After bathing, the elephant will usually use its trunk to blow dust onto its body and this dries into a protective crust. Elephants have difficulty releasing heat through the skin because of their low surface-area-to-volume ratio, which is many times smaller than that of a human. They have even been observed lifting up their legs, to expose their soles to the air. Sweat glands are absent in the elephant's skin, but water diffuses through the skin, allowing cooling by evaporative loss. In addition, the interconnected crevices in the elephant's skin is thought to impede dehydration and improve thermal regulation over a long period of time.

Legs, locomotion, and posture

To support the animal's weight, an elephant's limbs are positioned more vertically under the body than in most other mammals. The long bones of the limbs have cancellous bone in place of medullary cavities. This strengthens the bones while still allowing haematopoiesis (blood cell creation). Both the front and hind limbs can support an elephant's weight, although 60% is borne by the front. The position of the limbs and leg bones allow an elephant to stand still for extended periods of time without tiring. Elephants are incapable of turning their manus, as the ulna and radius of the front legs are secured in pronation. Elephants may also lack the pronator quadratus and pronator teres muscles or have very small ones. The circular feet of an elephant have soft tissues or "cushion pads" beneath the manus or pes, which distribute the weight of the animal. They appear to have a sesamoid, an extra "toe" similar in placement to a giant panda's extra "thumb", that also helps in weight distribution. As many as five toenails can be found on both the front and hind feet.

Elephants can move both forwards and backwards, but is incapable of trotting, jumping, or galloping. They can move on land only by walking or ambling: a faster gait similar to running. In walking, the legs act as pendulums, with the hips and shoulders rising and falling while the foot is planted on the ground. With no "aerial phase", the fast gait does not meet all the criteria of running, although the elephant uses its legs much like other running animals, with the hips and shoulders falling and then rising while the feet are on the ground. Fast-moving elephants appear to 'run' with their front legs, but 'walk' with their hind legs and can reach a top speed of 25 km/h (16 mph). At this speed, most other quadrupeds are well into a gallop, even accounting for leg length. Spring-like kinetics could explain the difference between the motion of elephants and other animals. During locomotion, the cushion pads expand and contract, and reduce both the pain and noise that would come from a very heavy animal moving. Elephants are capable swimmers: they can swim for up to six hours while staying at the surface, moving at 2.1 km/h (1 mph) and traversing up to 48 km (30 mi) continuously.

Internal systems

The brain of an elephant weighs 4.5–5.5 kg (10–12 lb) compared to 1.6 kg (4 lb) for a human brain. It is the largest of all terrestrial mammals. While the elephant brain is larger overall, it is proportionally smaller than the human brain. At birth, an elephant's brain already weighs 30–40% of its adult weight. The cerebrum and cerebellum are well developed, and the temporal lobes are so large that they bulge out laterally. Their temporal lobes are proportionally larger than in other animals, including humans. The throat of an elephant appears to contain a pouch where it can store water for later use. The larynx of the elephant is the largest known among mammals. The vocal folds are long and are attached close to the epiglottis base. When comparing an elephant's vocal folds to those of a human, an elephant's are longer, thicker, and have a larger cross-sectional area. In addition, they are tilted at 45 degrees and positioned more anteriorly than a human's vocal folds.

The heart of an elephant weighs 12–21 kg (26–46 lb). It's apex has two pointed ends, an unusual trait among mammals. In addition, the ventricles separate near the top of the heart, a trait they share with sirenians. When standing, the elephant's heart beats approximately 30 times per minute. Unlike many other animals, the heart rate speeds up by 8 to 10 beats per minute when the elephant is lying down. The blood vessels in most of the body are wide and thick and can withstand high blood pressures. The lungs are attached to the diaphragm, and breathing relies less on the expanding of the ribcage.Connective tissue exists in place of the pleural cavity. This may allow the animal to deal with the pressure differences when its body is underwater and its trunk is breaking the surface for air, although this explanation has been questioned. Another possible function for this adaptation is that it helps the animal suck up water through the trunk. Elephants inhale mostly with the trunk, but also with the mouth. They have a hindgut fermentation system, and their large and small intestines together reach 35 m (115 ft) in length. Less than half of an elephant's food intake gets digested, dispute the process lasting a day.

Sex organs

A male elephant's testes are located internally near the kidneys. The penis can be as long as 100 cm (39 in) with a 16 cm (6 in) wide base. It curves to an 'S' when fully erect and has an orifice shaped like a Y. The female's clitoris may be 40 cm (16 in). The vulva is found lower than in other herbivores, between the hind legs instead of under the tail. Determining pregnancy status can be difficult due to the animal's large belly. The female's mammary glands occupy the space between the front legs, which puts the suckling calf within reach of the female's trunk. Elephants have a unique organ, the temporal gland, located in both sides of the head. This organ is associated with sexual behaviour, and males secrete a fluid from it when in musth. Females have also been observed with these secretions.

Natural history

Elephants are herbivorous and will eat leaves, twigs, fruit, bark, grass and roots. African elephants mostly browse while Asian elephants mainly graze. They can eat as much as 300 kg (660 lb) of food and drink 40 L (11 US gal) of water in a day. Elephants tend to stay near water sources. They have morning, afternoon and nighttime feeding sessions. At midday, elephants rest under trees and may doze off while standing. Sleeping occurs at night while the animal is lying down. Elephants average 3–4 hours of sleep per day. Both males and family groups typically move no more than 20 km (12 mi) a day, but distances as far as 180 km (112 mi) have been recorded in the Etosha region of Namibia. Elephants go on seasonal migrations in response to changes in envrinmental conditions. At Chobe National Park, Botswana, herds travel 325 km (202 mi) to visit the river when the local waterholes dry up.

Because of their large size, elephants have a huge impact on their environments and are considered keystone species. Their habit of uprooting trees and undergrowth can transform savannah into grasslands; when they dig for water during drought, they create waterholes that can be used by other animals. When they use waterholes, they end up making them bigger. Smaller herbivores can access trees mowed down by elephants. At Mount Elgon, elephants dig through caves and pave the way for ungulates, hyraxes, bats, birds and insects. Elephants are important seed dispersers; African forest elephants ingest and defecate seeds, with either no effect or a positive effect on germination. The seeds are typically dispersed in large amounts over great distances. In Asian forests, large seeds require giant herbivores like elephants and rhinoceros for transport and dispersal. This ecological niche cannot be filled by the next largest herbivore, the tapir. Because most of the food elephants eat goes undigested, their dung can provide food for other animals, such as dung beetles and monkeys. Elephants can have a negative impact on ecosystems. At Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda, elephants numbers have threatened several species of small birds that depend on woodlands. Their weight causes the soil to compress, leading to run off and erosion.

Elephants typically coexist peacefully with other herbivores, which will usually stay out of their way. Some aggressive interactions between elephants and rhinoceros have been recorded. The size of adult elephants makes them nearly invulnerable to predators. Calves may be preyed on by lions, spotted hyenas, and wild dogs in Africa and tigers in Asia. The lions of Savuti, Botswana, have adapted to hunting elephants, mostly calves, juveniles or even sub-adults. There are rare reports of adult Asian elephants falling prey to tigers. Elephants tend to have high numbers of parasites, particularly nematodes, compared to many other mammals. This is due to them being largely immune to predators, which would otherwise kill off many of the individuals with significant parasite loads.

Social organisation

Female elephants spend their entire lives in tight-knit matrilineal family groups. They are led by the matriarch which is often the eldest female. She remains leader of the group until death or if she no longer has the energy for the role; a study on zoo elephants showed that when the matriarch died, the levels of faecal corticosterone ('stress hormone') dramatically increased in the surviving elephants. When her tenure is over, the matriarch's eldest daughter takes her place; this occurs even if her sister is present. One study found that younger matriarchs are more likely than older ones to under-react to severe danger. Family groups may split after becoming too large for the available resources.

At Amboseli National Park, Kenya, female groups may consist of around ten members, including four adults and their dependent offspring. Here, a female's life involves interaction with those outside her group. Two separate families may associate and bond with each other, forming what are known as bond groups. During the dry season, elephant families may aggregate together into clans. These may number around nine groups, which clans do not form strong bonds, but defend their dry-season ranges against other clans. The Amboseli elephant population is further divided into the "central" and "peripheral" subpopulations.

Elephants of India and Sri Lanka may have similar group organisations. In Sri Lanka, there appear to be stable family units or "herds" and larger, looser "groups". They have been observed to have "nursing units" and "juvenile-care units". In southern India, elephant populations may contain family groups, bond groups and possibly clans. Family groups tend to be small, with only one or two adult females and their offspring. A group containing more than two adult females and their offspring is known as a "joint family". Malay elephant populations have even smaller family units and do not reach levels above a bond group. Groups of African forest elephants typically consist of one adult female with one to three offspring. These groups appear to interact with each other, especially at forest clearings.

The social life of the adult male is very different. As he matures, a male associates more with outside males or even other families. At Amboseli, young males may be away from their families 80% by 14–15 years of age. When males permanently leave, they either live alone or with other males. The former is typical of bulls in dense forests. Asian males are usually solitary, but occasionally form groups of two or more individuals; the largest consisted of seven bulls. Male groups consisting of over 10 members occur only among African bush elephants, the largest of which numbered up to 144 individuals.

Male elephants can be quite sociable when not competing for dominance or mates, and will form long-term relationships. A dominance hierarchy exists among males, whether they are social or solitary. Dominance depends on the age, size and sexual condition, and when in groups, males follow the lead of the dominant bull. Young bulls may seek out the company and leadership of older, more experienced males, whose presence appears to control their aggression and prevent them from exhibiting "deviant" behaviour. Adult males and females come together to breed. Bulls will accompany family groups if a cow is in oestrous.

Sexual behaviour

Musth

Adult males enter a state of increased testosterone known as musth. In a population in southern India, males first enter musth at 15 years old, but it is not very intense until they are older than 25. At Amboseli, no bulls under 24 were found to be in musth, while half of those aged 25–35 and all those over 35 did. In some areas, there may be seasonal influences on the timing of musths. The main characteristic of a bull's musth is a fluid discharged from the temporal gland that runs down the side of his face. Behaviours associated with musth include walking with a high and swinging head, nonsynchronous ear flapping, picking at the ground with the tusks, marking, rumbling, and urinating in the sheath. The length of this varies between males of different ages and conditions, lasting days to months.

Males become extremely aggressive during musth. Size is the determining factor in agonistic encounters when the individuals have the same condition. In contests between musth and non-musth individuals, musth bulls win the majority of the time, even when the non-musth bull is larger. A male may stop showing signs of musth when he encounters a musth male of higher rank. Those of equal rank tend to avoid each other. Agonistic encounters typically consist of threat displays, chases, and minor sparring. Rarely do they full-on fight.

Mating

Elephants are polygynous breeders, and most copulations occur during rainfall. An oestrus cow uses pheromones in her urine and vaginal secretions to signal her readiness to mate. A bull will follow a potential mate and assess her condition with the flehmen response, which requires the male to collect a chemical sample with his trunk and taste it with the vomeronasal organ at the roof of the mouth. The oestrous cycle of a cow lasts 14–16 weeks with a 4–6-week follicular phase and an 8- to 10-week luteal phase. While most mammals have one surge of luteinizing hormone during the follicular phase, elephants have two. The first (or anovulatory) surge, could signal to males that the female is in oestrus by changing her scent, but ovulation does not occur until the second (or ovulatory) surge. Cows over 45–50 years of age are less fertile.

Bulls engage in a behaviour known as mate-guarding, where they follow oestrous females and defend them from other males. Most mate-guarding is done by musth males, and females seek them out, particularly older ones. Musth appears to signal to females the condition of the male, as weak or injured males do not have normal musths. For young females, the approach of an older bull can be intimidating, so her relatives stay nearby for comfort. During copulation, the male rests his trunk on the female. The penis is very mobile, being able to move independently of the pelvis. Before mounting, it curves forward and upward. Copulation lasts about 45 seconds and does not involve pelvic thrusting or ejaculatory pause. Elephant sperm must swim close to 2 m (6.6 ft) to reach the egg. By comparison, human sperm has to swim around only 76.2 mm (3.00 in).

Homosexual behaviour is frequent in both sexes. As in heterosexual interactions, this involves mounting. Male elephants sometimes stimulate each other by playfighting and "championships" may form between old bulls and younger males. Female same-sex behaviours have been documented only in captivity where they are known to masturbate one another with their trunks.

Birth and development

Gestation in elephants typically lasts between one and a half and two years and the female will not give birth again for at least four years. Births tend to take place during the wet season. Calves are born 85 cm (33 in) tall and with a weight of around 120 kg (260 lb). Typically, only a single young is born, but twins sometimes occur. The relatively long pregnancy is maintained by five corpus luteums (as opposed to one in most mammals) and gives the foetus more time to develop, particularly the brain and trunk. As such, newborn elephants are precocial and quickly stand and walk to follow their mother and family herd. A newborn calf will attract the attention of all the herd members. Adults and most of the other young will gather around the newborn, touching and caressing it with their trunks. For the first few days, the mother controls the access of the other herd members to her young. Alloparenting – where a calf is cared for by someone other than its mother – takes place in some family groups. Allomothers are typically aged two to twelve years.

For the first few days, the newborn is unsteady on its feet and needs its mother's help. It relies on touch, smell, and hearing, as its eyesight is less developed. With little coordination in its trunk, it can only flop it around which may cause it to trip. When it reaches its second week, the calf can walk with more balance and has more control over its trunk. After its first month, the trunk can grab and hold objects, but still lacks sucking abilities, and the calf must bend down to drink. It continues to stay near its mother as it is still reliant on her. For its first three months, a calf relies entirely on its mother's milk, after which it begins to forage for vegetation and can use its trunk to collect water. At the same time, there is progress in lip and leg movements. By nine months, mouth, trunk and foot coordination are complete. Suckling bouts tend to last 2–4 min/hr for a calf younger than a year. After a year, a calf is fully capable of grooming, drinking, and feeding itself. It still needs its mother's milk and protection until it is at least two years old. Suckling after two years may improve growth, health and fertility.

Play behaviour in calves differs between the sexes; females run or chase each other while males play-fight. The former are sexually mature by the age of nine years while the latter become mature around 14–15 years. Adulthood starts at about 18 years of age in both sexes. Elephants have long lifespans, reaching 60–70 years of age.Lin Wang, a captive male Asian elephant, lived for 86 years.

Communication

Touching is an important form of communication among elephants. Individuals greet each other by touching each other on the mouth, temporal glands and genitals. This allows them to pick up chemical cues. Older elephants use trunk-slaps, kicks, and shoves to control younger ones. Touching is especially important for mother–calf communication. When moving, elephant mothers will touch their calves with their trunks or feet when side-by-side or with their tails if the calf is behind them. A calf will press against its mother's front legs to signal it wants to rest and will touch her breast or leg when it wants to suckle.

Visual displays mostly occur in agonistic situations. Elephants will try to appear more threatening by raising their heads and spreading their ears. They may add to the display by shaking their heads and snapping their ears, as well as tossing around dust and vegetation. They are usually bluffing when performing these actions. Excited elephants also raise their heads and spread their ears but additionally may raise their trunks. Submissive elephants will lower their heads and trunks, as well as flatten their ears against their necks, while those that are ready to fight will bend their ears in a V shape.

Elephants produce several vocalisations, some of which pass though the trunk, for both short and long range communication. These include trumpets, bellows, roars, growls, barks, snorts, and rumbles. Elephants may produce infrasonic rumbles. For Asian elephants, these calls have a frequency of 14–24 Hz, with sound pressure levels of 85–90 dB and last 10–15 seconds. For African elephants, calls range from 15 to 35 Hz with sound pressure levels as high as 117 dB, allowing communication for many kilometres, with a possible maximum range of around 10 km (6 mi).

Elephants are known to communicate with seismics, vibrations produced by impacts on the earth's surface or acoustical waves that travel through it. An individual running or mock charging can create seismic signals that can be heard at travel distances of up to 32 km (20 mi). Seismic waveforms produced from predator alarm calls travel 16 km (10 mi).

Intelligence and cognition

Elephants exhibit mirror self-recognition, an indication of self-awareness and cognition that has also been demonstrated in some apes and dolphins. One study of a captive female Asian elephant suggested the animal was capable of learning and distinguishing between several visual and some acoustic discrimination pairs. This individual was even able to score a high accuracy rating when re-tested with the same visual pairs a year later. Elephants are among the species known to use tools. An Asian elephant has been observed modifying branches and using them as flyswatters. Tool modification by these animals is not as advanced as that of chimpanzees. Elephants are popularly thought of as having an excellent memory. This could have a factual basis; they possibly have cognitive maps to allow them to remember large-scale spaces over long periods of time. Individuals appear to be able to keep track of the current location of their family members.

Scientists debate the extent to which elephants feel emotion. They appear to show interest in the bones of their own kind, regardless of whether they are related. As with chimpanzees and dolphins, a dying or dead elephant may elicit attention and aid from others, including those from other groups. This has been interpreted as expressing "concern"; however, others would dispute such an interpretation as being anthropomorphic; the Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour (1987) advised that "one is well advised to study the behaviour rather than attempting to get at any underlying emotion".

Conservation

Status

African bush elephants were listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2021, and African forest elephants were listed as Critically Endangered in the same year. In 1979, Africa had an estimated population of at least 1.3 million elephants, possibly as high as 3.0 million. A decade later, the population was estimated to be 609,000; with 277,000 in Central Africa, 110,000 in Eastern Africa, 204,000 in Southern Africa, and 19,000 in Western Africa. The population of rainforest elephants was lower than anticipated, at around 214,000 individuals. Between 1977 to 1989, elephant populations declined by 74% in East Africa. After 1987, losses in elephant numbers hastened, and savannah populations from Cameroon to Somalia experienced a decline of 80%. African forest elephants had a total loss of 43%. Population trends in southern Africa were various, with unconfirmed losses in Zambia, Mozambique and Angola while populations grew in Botswana and Zimbabwe and were stable in South Africa. Conversely, studies in 2005 and 2007 found populations in eastern and southern Africa were increasing by an average annual rate of 4.0%. The IUCN estimated that total population in Africa is estimated at around to 415,000 individuals for both species combined as of 2016.

African elephants receive at least some legal protection in every country where they are found, but 70% of their range exists outside protected areas. Successful conservation efforts in certain areas have led to high population densities. As of 2008, local numbers were controlled by contraception or translocation. Large-scale cullings ceased in 1988 when Zimbabwe abandoned the practice. In 1989, the African elephant was listed under Appendix I by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), making trade illegal. Appendix II status (which allows restricted trade) was given to elephants in Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe in 1997 and South Africa in 2000. In some countries, sport hunting of the animals is legal; Botswana, Cameroon, Gabon, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have CITES export quotas for elephant trophies.

In 2020, the IUCN listed the Asian elephant as endangered due to an almost 50% population decline over "the last three generations". Asian elephants once ranged from Western to East Asia and south to Sumatra. and Java. It is now extinct in these areas, and the current range of Asian elephants is highly fragmented. The total population of Asian elephants is estimated to be around 40,000–50,000, although this may be a loose estimate. Around 60% of the population is in India. Although Asian elephants are declining in numbers overall, particularly in Southeast Asia, the population in the Western Ghats appears to be increasing.

Threats

The poaching of elephants for their ivory, meat and hides has been one of the major threats to their existence. Historically, numerous cultures made ornaments and other works of art from elephant ivory, and its use was comparable to that of gold. The ivory trade contributed to the African elephant population decline in the late 20th century. This prompted international bans on ivory imports, starting with the United States in June 1989, and followed by bans in other North American countries, western European countries, and Japan. Around the same time, Kenya destroyed all its ivory stocks. Ivory was banned internationally by CITES in 1990. Following the bans, unemployment rose in India and China, where the ivory industry was important economically. By contrast, Japan and Hong Kong, which were also part of the industry, were able to adapt and were not as badly affected. Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Malawi wanted to continue the ivory trade and were allowed to, since their local elephant populations were healthy, but only if their supplies were from elephants that had been culled or died of natural causes.

The ban allowed the elephant to recover in parts of Africa. In January 2012, 650 elephants in Bouba Njida National Park, Cameroon, were killed by Chadian raiders. This has been called "one of the worst concentrated killings" since the ivory ban. Asian elephants are potentially less vulnerable to the ivory trade, as females usually lack tusks. Still, members of the species have been killed for their ivory in some areas, such as Periyar National Park in India. China was the biggest market for poached ivory but announced they would phase out the legal domestic manufacture and sale of ivory products in May 2015, and in September 2015, China and the United States said "they would enact a nearly complete ban on the import and export of ivory" due to causes of extinction.

Other threats to elephants include habitat destruction and fragmentation. The Asian elephant lives in areas with some of the highest human populations and may be confined to small islands of forest among human-dominated landscapes. Elephants commonly trample and consume crops, which contributes to conflicts with humans, and both elephants and humans have died by the hundreds as a result. Mitigating these conflicts is important for conservation. One proposed solution is the protection of wildlife corridors which gave the animals greater space and maintain the long term viability of large populations.

Humans relations

Working animal

Elephants have been working animals since at least the Indus Valley civilization over 4,000 years ago and continue to be used in modern times. There were 13,000–16,500 working elephants employed in Asia in 2000. These animals are typically captured from the wild when they are 10–20 years old when they are both more trainable and can work for more years. They were traditionally captured with traps and lassos, but since 1950, tranquillisers have been used. Individuals of the Asian species have been often trained as working animals. Asian elephants are used to carry and pull both objects and people in and out of areas as well as lead people in religious celebrations. They are valued over mechanised tools has they can perform the same tasks but in more difficult terrain, with strength, memory, and delicacy. Elephants can learn over 30 commands. Musth bulls can be difficult and dangerous to work with and are chained up until the condition passes.

In India, many working elephants are alleged to have been subject to abuse. They and other captive elephants are thus protected under The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960. In both Myanmar and Thailand, deforestation and other economic factors have resulted in sizable populations of unemployed elephants resulting in health problems for the elephants themselves as well as economic and safety problems for the people amongst whom they live.

The practice of working elephants has also been attempted in Africa. The taming of African elephants in the Belgian Congo began by decree of Leopold II of Belgium during the 19th century and continues to the present with the Api Elephant Domestication Centre.

Warfare

Historically, elephants were considered formidable instruments of war. They were descripted in Sanskrit texts as far back as 1500 BC. From South Asia, the use of elephants in warfare spread west to Persia and east to Southeast Asia. The Persians used them during the Achaemenid Empire (between the 6th and 4th centuries BC) while Southeast Asian states first used war elephants possibly as early as the 5th century BC and continued to the 20th century. War elephants were also employed in the Mediterranean and North Africa throughout the classical period since the reign of Ptolemy II in Egypt. The Carthaginian general Hannibal took African elephants across the Alps during his war with the Romans and reached the Po Valley in 218 BC with all of them alive, but died of disease and combat a year later.

Their heads and sides were equipped with armour, the trunk may have a sword tied to it and tusks were sometimes covered sharpened iron or brass. Trained elephants would attack both humans and horses with their tusks. They may as grasp an enemy soldier with the trunk and toss him to their rider or to pin the soldier to the ground and spear him. Some weakness of war elephants included their great visibility, which made them easy to target, and limited maneuverability compared to horses. Alexander the Great achieved victory over armies with war elephants by having his soldiers injure the trunks and legs of the animals which caused them to panic and become uncontrollable.

Zoos and circuses

Elephants have traditionally been a major part of zoos and circuses around the world. In circuses, they are trained to perform tricks. The most famous circus elephant was probably Jumbo (1861 – 15 September 1885), who was a major attraction in the Barnum & Bailey Circus. These animals do not reproduce well in captivity, due to the difficulty of handling musth bulls and limited understanding of female oestrous cycles. Asian elephants were always more common than their African counterparts in modern zoos and circuses. After CITES listed the Asian elephant under Appendix I in 1975, imports of the species almost stopped by the end of the 1980s. Subsequently, the US received many captive African elephants from Zimbabwe, which had an overabundance of the animals.

Keeping elephants in zoos has met with some controversy. Proponents of zoos argue that they offer researchers easy access to the animals and provide money and expertise for preserving their natural habitats, as well as safekeeping for the species. Critics claim that the animals in zoos are under physical and mental stress. Elephants have been recorded displaying stereotypical behaviours in the form of swaying back and forth, trunk swaying, or route tracing. This has been observed in 54% of individuals in UK zoos. Elephants in European zoos appear to have shorter lifespans than their wild counterparts at only 17 years, although other studies suggest that zoo elephants live as long those in the wild.

The use of elephants in circuses has also been controversial; the Humane Society of the United States has accused circuses of mistreating and distressing their animals. In testimony to a US federal court in 2009, Barnum & Bailey Circus CEO Kenneth Feld acknowledged that circus elephants are struck behind their ears, under their chins and on their legs with metal-tipped prods, called bull hooks or ankus. Feld stated that these practices are necessary to protect circus workers and acknowledged that an elephant trainer was reprimanded for using an electric shock device, known as a hot shot or electric prod, on an elephant. Despite this, he denied that any of these practices harm elephants. Some trainers have tried to train elephants without the use of physical punishment. Ralph Helfer is known to have relied on positive reinforcement when training his animals. Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey circus retired its touring elephants in May 2016.

Attacks

Elephants can exhibit bouts of aggressive behaviour and engage in destructive actions against humans. In Africa, groups of adolescent elephants damaged homes in villages after cullings in the 1970s and 1980s. Because of the timing, these attacks have been interpreted as vindictive. In parts of India, male elephants regularly enter villages at night, destroying homes and killing people. Elephants killed around 300 people between 2000 and 2004 in Jharkhand while in Assam, 239 people were reportedly killed between 2001 and 2006. Local people have reported their belief that some elephants were drunk during their attacks, although officials have disputed this explanation. Purportedly drunk elephants attacked an Indian village a second time in December 2002, killing six people, which led to the killing of about 200 elephants by locals.

Cultural depictions

Elephants have a universal presence in global culture. They have been represented in art since Paleolithic times. Africa, in particular, contains many examples of elephant rock art, especially in the Sahara and southern Africa. In Asia, the animals are depicted as motifs in Hindu and Buddhist shrines and temples. Elephants were often difficult to portray by people with no first-hand experience of them. The ancient Romans, who kept the animals in captivity, depicted anatomically accurate elephants on mosaics in Tunisia and Sicily. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, when Europeans had little to no access to the animals, elephants were portrayed more like fantasy creatures. They were given with horse, bovine and boar-like traits, and their trunks were drawn like trumpets. Stonemasons used the images of elephants for Gothic churches. As Europeans gained more access to captive elephants during the 15th century, depictions of them became more accurate, including one made by Leonardo da Vinci. Despite this, some Europeans continued to portray them in a more stylised fashion.

Elephants have been the subject of religious beliefs. The Mbuti people of central Africa believe that the souls of their dead ancestors resided in elephants. Similar ideas existed among other African societies, who believed that their chiefs would be reincarnated as elephants. During the 10th century AD, the people of Igbo-Ukwu, in modern day Nigeria, placed elephant tusks underneath their death leader's feet in the grave. The animals' importance is only totemic in Africa but is much more significant in Asia. In Sumatra, elephants have been associated with lightning. Likewise in Hinduism, they are linked with thunderstorms as Airavata, the father of all elephants, represents both lightning and rainbows. One of the most important Hindu deities, the elephant-headed Ganesha, is ranked equal with the supreme gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma in some traditions. Ganesha is associated with writers and merchants and it is believed that he can give people success as well as grant them their desires, but could also take these things away. In Buddhism, Buddha is said to have been a white elephant reincarnated as a human.

Elephants are ubiquitous in Western popular culture as emblems of the exotic, especially since – as with the giraffe, hippopotamus and rhinoceros – there are no similar animals familiar to Western audiences. As characters, elephants are most common in children's stories, in which they are generally cast as models of exemplary behaviour. They are typically surrogates for humans with ideal human values. Many stories tell of isolated young elephants returning to a close-knit community, such as "The Elephant's Child" from Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, Disney's Dumbo, and Kathryn and Byron Jackson's The Saggy Baggy Elephant. Other elephant heroes given human qualities include Jean de Brunhoff's Babar, David McKee's Elmer, and Dr. Seuss's Horton.

Several cultural references emphasise the elephant's size and exotic uniqueness. For instance, a "white elephant" is a byword for something expensive, useless, and bizarre. The expression "elephant in the room" refers to something that is being ignored but ultimately must be addressed. The story of the blind men and an elephant involves blind men touching different parts of an elephant and try to figure out what it is.

See also

- Animal track

- Beehive fences use elephants' fear of bees to minimise conflict with humans

- Desert elephant

- Dwarf elephant

- Elephants' graveyard

- List of individual elephants

- Motty, captive hybrid of an Asian and African elephant

- National Elephant Day (Thailand)

- World Elephant Day

Bibliography

-

Shoshani, J., ed. (2000). Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-87596-143-9. OCLC 475147472.

- Shoshani, J.; Shoshani, S. L. "What Is an Elephant?". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 14–15.

- Shoshani, J. "Comparing the Living Elephants". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 36–51.

- Shoshani, J. "Anatomy and Physiology". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 66–80.

- Easa, P. S. "Musth in Asian Elephants". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 85–86.

- Moss, C. "Elephant Calves: The Story of Two Sexes". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 106–13.

- Payne, K. B.; Langauer, W. B. "Elephant Communication". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 116–23.

- Eltringham, S. K. "Ecology and Behavior". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 124–27.

- Wylie, K. C. "Elephants as War Machines". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 146–48.

- McNeely, J. A. "Elephants as Beasts of Burden". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 149–50.

- Smith, K. H. "The Elephant Domestication Centre of Africa". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 152–54.

- McNeely, J. A. "Elephants in Folklore, Religion and Art". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 158–65.

- Shoshani, S. L. "Famous Elephants". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 168–71.

- Daniel, J. C. "The Asian Elephant Population Today". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 174–77.

- Douglas-Hamilton, I. "The African Elephant Population Today". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 178–83.

- Tuttle, C. D. "Elephants in Captivity". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 184–93.

- Martin, E. B. "The Rise and Fall of the Ivory Market". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 202–07.

- Shoshani, J. "Why Save Elephants?". Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. pp. 226–29.

- Sukumar, R. (11 September 2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-510778-4. OCLC 935260783.

- Kingdon, J. (29 December 1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part B: Large Mammals. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-43722-4. OCLC 468569394. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Wylie, D. (15 January 2009). Elephant. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-615-5. OCLC 740873839. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

Further reading

- Carrington, Richard (1958). Elephants: A Short Account of their Natural History, Evolution and Influence on Mankind. Chatto & Windus. OCLC 911782153.

- Nance, Susan (2013). Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

- Saxe, John Godfrey (1872). "The Blindmen and the Elephant" at Wikisource. The Poems of John Godfrey Saxe.

- Williams, Heathcote (1989). Sacred Elephant. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-517-57320-4.

External links

| General |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human use |

|

||||||

| Culture and history |

|

||||||

| Related | |||||||

|

Extant Proboscidea species by family

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

|

Elephantidae (Elephants) |

|

||||

|

Genera of the order Proboscidea

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National | |

|---|---|

| Other | |