Extended evolutionary synthesis

The extended evolutionary synthesis consists of a set of theoretical concepts argued to be more comprehensive than the earlier modern synthesis of evolutionary biology that took place between 1918 and 1942. The extended evolutionary synthesis was called for in the 1950s by C. H. Waddington, argued for on the basis of punctuated equilibrium by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge in the 1980s, and was reconceptualized in 2007 by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd B. Müller. Notably, Dr. Müller concluded from this research that Natural Selection has no way of explaining speciation, saying: “selection has no innovative capacity...the generative and the ordering aspects of morphological evolution are thus absent from evolutionary theory.”

The extended evolutionary synthesis revisits the relative importance of different factors at play, examining several assumptions of the earlier synthesis, and augmenting it with additional causative factors. It includes multilevel selection, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, niche construction, evolvability, and several concepts from evolutionary developmental biology.

Not all biologists have agreed on the need for, or the scope of, an extended synthesis. Many have collaborated on another synthesis in evolutionary developmental biology, which concentrates on developmental molecular genetics and evolution to understand how natural selection operated on developmental processes and deep homologies between organisms at the level of highly conserved genes.

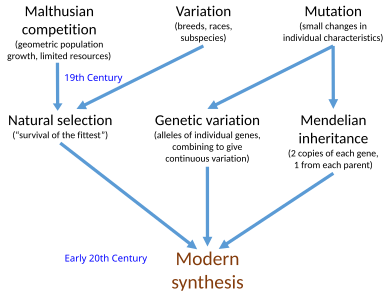

The preceding "modern synthesis"

The modern synthesis was the widely accepted early-20th-century synthesis reconciling Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection and Gregor Mendel's theory of genetics in a joint mathematical framework. It established evolution as biology's central paradigm. The 19th-century ideas of natural selection by Darwin and Mendelian genetics were united by researchers who included Ronald Fisher, J. B. S. Haldane and Sewall Wright, the three founders of population genetics, between 1918 and 1932.Julian Huxley introduced the phrase "modern synthesis" in his 1942 book, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis.

Early history

During the 1950s, the English biologist C. H. Waddington called for an extended synthesis based on his research on epigenetics and genetic assimilation. An extended synthesis was also proposed by the Austrian zoologist Rupert Riedl, with the study of evolvability. In 1978, Michael J. D. White wrote about an extension of the modern synthesis based on new research from speciation.

1980s: punctuated equilibrium

In the 1980s, the American palaeontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge argued for an extended synthesis based on their idea of punctuated equilibrium, the role of species selection shaping large scale evolutionary patterns and natural selection working on multiple levels extending from genes to species. The ethologist John Endler wrote a paper in 1988 discussing processes of evolution that he felt had been neglected.

Contributions from evolutionary developmental biology

Some researchers in the field of evolutionary developmental biology proposed another synthesis. They argue that the modern and extended syntheses should mostly center on genes and suggest an integration of embryology with molecular genetics and evolution, aiming to understand how natural selection operates on gene regulation and deep homologies between organisms at the level of highly conserved genes, transcription factors and signalling pathways. By contrast, a different strand of evo-devo following an organismal approach contributes to the extended synthesis by emphasizing (amongst others) developmental bias (both through facilitation and constraint), evolvability, and inherency of form as primary factors in the evolution of complex structures and phenotypic novelties.

Recent history

The idea of an extended synthesis was relaunched in 2007 by Massimo Pigliucci, and Gerd B. Müller, with a book in 2010 titled Evolution: The Extended Synthesis, which has served as a launching point for work on the extended synthesis. This includes:

- The role of prior configurations, genomic structures, and other traits in the organism in generating evolutionary variations.

- How increasing dimensionality of fitness landscapes affects our view of speciation.

- The role of multilevel selection in the major evolutionary transitions.

- New types of inheritance, including cultural and epigenetic inheritance.

- The way that organismal development and developmental plasticity channel evolutionary pathways and generates phenotypic novelty

- How organisms modify the environments they belong to through niche construction.

Other processes such as evolvability, phenotypic plasticity, reticulate evolution, sex evolution and symbiogenesis are said by proponents to have been excluded or missed from the modern synthesis. The goal of Piglucci's and Müller's extended synthesis is to take evolution beyond the gene-centered approach of population genetics to consider more organism- and ecology-centered approaches. Many of these causes are currently considered secondary in evolutionary causation, and proponents of the extended synthesis want them to be considered first-class evolutionary causes. The biologist Eugene Koonin wrote in 2009 that "the new developments in evolutionary biology by no account should be viewed as refutation of Darwin. On the contrary, they are widening the trails that Darwin blazed 150 years ago and reveal the extraordinary fertility of his thinking."

Predictions

The extended synthesis is characterized by its additional set of predictions that differ from the standard modern synthesis theory:

- change in phenotype can precede change in genotype

- changes in phenotype are predominantly positive, rather than neutral (see: neutral theory of molecular evolution)

- changes in phenotype are induced in many organisms, rather than one organism

- revolutionary change in phenotype can occur through mutation, facilitated variation or threshold events

- repeated evolution in isolated populations can be by convergent evolution or developmental bias

- adaptation can be caused by natural selection, environmental induction, non-genetic inheritance, learning and cultural transmission (see: Baldwin effect, meme, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, ecological inheritance, non-Mendelian inheritance)

- rapid evolution can result from simultaneous induction, natural selection and developmental dynamics

- biodiversity can be affected by features of developmental systems such as differences in evolvability

- heritable variation is directed towards variants that are adaptive and integrated with phenotype

- niche construction is biased towards environmental changes that suit the constructor's phenotype, or that of its descendants, and enhance their fitness

- kin selection

- multilevel selection

- self-organization

Testing

During 2016–2019 the extended evolutionary synthesis was tested by a group of scientists from eight institutions in Britain, Sweden and the United States. The £7.7 million project was supported by a £5.7 million grant from the John Templeton Foundation. Publications from the project include over 200 papers, a special issue, and an anthology on Evolutionary Causation. In 2019 a final report of the 2016–2019 consortium was published, Putting the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis to the Test.

The project was headed by Kevin N. Laland at the University of St Andrews and Tobias Uller at Lund University. According to Laland what the extended synthesis "really boils down to is recognition that, in addition to selection, drift, mutation and other established evolutionary processes, other factors, particularly developmental influences, shape the evolutionary process in important ways."

Status

Biologists disagree on the need for an extended synthesis. Opponents contend that the modern synthesis is able to fully account for the newer observations, whereas others criticize the extended synthesis for not being radical enough. Proponents think that the conceptions of evolution at the core of the modern synthesis are too narrow and that even when the modern synthesis allows for the ideas in the extended synthesis, using the modern synthesis affects the way that biologists think about evolution. For example, Denis Noble says that using terms and categories of the modern synthesis distorts the picture of biology that modern experimentation has discovered. Proponents therefore claim that the extended synthesis is necessary to help expand the conceptions and framework of how evolution is considered throughout the biological disciplines.

In 2021, the John Templeton Foundation published a review of recent literature.

Further reading

Defence of the extended synthesis

- Arnold, Anthony J; Fristrup, Kurt (1982). "The Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection: A Hierarchical Expansion". Paleobiology. 8 (2): 113–129. doi:10.1017/s0094837300004462. S2CID 124286915.

- Boto, Luis (2010). "Horizontal Gene Transfer in Evolution: Facts and Challenges". Proc Biol Sci. 277 (1683): 819–827. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1679. PMC 2842723. PMID 19864285.

- Carroll, Sean B (2008). "Evo-Devo and an Expanding Evolutionary Synthesis: A Genetic Theory of Morphological Evolution". Cell. 134 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.030. PMID 18614008. S2CID 2513041.

- Endler, John (1986). "The Newer Synthesis? Some Conceptual Problems in Evolutionary Biology". Oxford Surveys in Evolutionary Biology. 3: 224–243.

- Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). "A New Evolutionary Synthesis". In Developmental Biology, 6th edition. Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-243-7

- Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J. (2008). "Soft Inheritance: Challenging the Modern Synthesis". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 31 (2): 389–395. doi:10.1590/s1415-47572008000300001.

- Koonin, Eugene (2009). "Towards a postmodern synthesis of evolutionary biology". Cell Cycle. 8 (6): 799–800. doi:10.4161/cc.8.6.8187. PMC 3410441. PMID 19242109.

- Koonin, Eugene (2009). "The Origin at 150: is a new evolutionary synthesis in sight?". Trends Genet. 25 (11): 473–475. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.007. PMC 2784144. PMID 19836100.

- Lodé, Thierry (2013). Manifeste pour une écologie évolutive, Darwin et après. Eds Odile Jacob, Paris.

- Messerly, J.G. (1992). Piaget's conception of evolution: Beyond Darwin and Lamarck. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8243-9.

- Müller, Gerd B. (2014). "EvoDevo Shapes the Extended Synthesis". Biol Theory. 9 (2): 119–121. doi:10.1007/s13752-014-0179-6.

- Pennisi, Elizabeth (2008). "Modernizing the Modern Synthesis". Science. 321 (5886): 196–197. doi:10.1126/science.321.5886.196. PMID 18621652. S2CID 33015565.

- Postdarwinism: "The New Synthesis". A review of Ecological Developmental Biology: Integrating Epigenetics, Medicine, and Evolution, by Scott F. Gilbert and David Epel (Sinauer, 2009).

- "Post-modern synthesis?" A review of Developmental Plasticity and Evolution by Mary Jane West-Eberhard (Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Schrey; et al. (2012). "The Role of Epigenetics in Evolution: The Extended Synthesis". Genetics Research International. 2012: 286164. doi:10.1155/2012/286164. PMC 3335599. PMID 22567381.

- Weber, Bruce H (2011). "Extending and Expanding the Darwinian Synthesis: The Role of Complex Systems Dynamics". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Science. 42 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.11.014. PMID 21300318.

- Whitfield, John (2008). "Biology theory: Postmodern evolution?". Nature. 455 (7211): 281–284. doi:10.1038/455281a. PMID 18800108.

Criticism of the extended synthesis

- Coyne, Jerry (November 24, 2014). "Does evolution need a revolution?". Why Evolution Is True (Blog). Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- Craig, Lindsay (2010). "The So-Called Extended Synthesis and Population Genetics". Biological Theory. 5 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1162/biot_a_00035. S2CID 84662773.

- Dickens, Thomas; Rahman, Qazi. (2012). "The extended evolutionary synthesis and the role of soft inheritance in evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society: B biological sciences, 279 (1740). pp. 2913–2921.

- Felsenstein, Joseph (1986). "Waiting for Post-Neo-Darwin". Evolution. 40 (4): 883–889. doi:10.2307/2408480. JSTOR 2408480. PMID 28556149.

- Haig, David (2007). "Weismann rules! OK? Epigenetics and the Lamarckian Temptation". Biology and Philosophy. 22 (3): 415–428. doi:10.1007/s10539-006-9033-y. S2CID 16322990.

- Kurland, CG; Canback, B; Berg, OG (2003). "Horizontal Gene Transfer: A Critical View". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100 (17): 9658–9662. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9658K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1632870100. PMC 187805. PMID 12902542.

- Lynch, Michael (2007). "The frailty of adaptive hypotheses for the origins of organismal complexity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (Suppl 1): 8597–8604. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8597L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702207104. PMC 1876435. PMID 17494740.

- Mayr, Ernst (2004). "80 years of watching the evolutionary scenery". Science. 305 (5680): 46–47. doi:10.1126/science.1100561. PMID 15232092.

- Merlin, Francesca (2010). "Evolutionary Chance Mutation: A Defense of the Modern Synthesis' Consensus View". Philosophy and Theory in Biology. 2 (20170609): 22. doi:10.3998/ptb.6959004.0002.003.

- Stebbins, Ledyard G.; Ayala, Francisco J. (1981). "Is a New Evolutionary Synthesis Necessary?". Science. 213 (4511): 967–971. Bibcode:1981Sci...213..967L. doi:10.1126/science.213.4511.967. PMID 17789015. S2CID 39048630.

External links

- Extended Evolutionary Synthesis

- Should Evolutionary Theory Evolve?, By Bob Grant, January 1, 2010 The Scientist.