Diethylstilbestrol

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), also known as stilbestrol or stilboestrol, is a nonsteroidal estrogen medication, which is presently rarely used. In the past, it was widely used for a variety of indications, including pregnancy support for those with a history of recurrent miscarriage, hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms and estrogen deficiency, treatment of prostate cancer and breast cancer, and other uses. By 2007, it was only used in the treatment of prostate cancer and breast cancer. In 2011, Hoover and colleagues reported on adverse health outcomes linked to DES including infertility, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, preeclampsia, preterm birth, stillbirth, infant death, menopause prior to age 45, breast cancer, cervical cancer, and vaginal cancer. While most commonly taken by mouth, DES was available for use by other routes as well, for instance, vaginal, topical, and by injection.

DES is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol. It is a synthetic and nonsteroidal estrogen of the stilbestrol group, and differs from the natural estrogen estradiol in various ways. Compared to estradiol, DES has greatly improved bioavailability when taken by mouth, is more resistant to metabolism, and shows relatively increased effects in certain parts of the body like the liver and uterus. These differences result in DES having an increased risk of blood clots, cardiovascular issues, and certain other adverse effects.

DES was discovered in 1938 and introduced for medical use in 1939. From about 1940 to 1971, the medication was given to pregnant women in the incorrect belief that it would reduce the risk of pregnancy complications and losses. In 1971, DES was shown to cause clear-cell carcinoma, a rare vaginal tumor, in those who had been exposed to this medication in utero. The United States Food and Drug Administration subsequently withdrew approval of DES as a treatment for pregnant women. Follow-up studies have indicated that DES also has the potential to cause a variety of significant adverse medical complications during the lifetimes of those exposed.

The United States National Cancer Institute recommends children born to mothers who took DES to undergo special medical exams on a regular basis to screen for complications as a result of the medication. Individuals who were exposed to DES during their mothers' pregnancies are commonly referred to as "DES daughters" and "DES sons". Since the discovery of the toxic effects of DES, it has largely been discontinued and is now mostly no longer marketed.

Medical uses

DES has been used in the past for the following indications:

- Recurrent miscarriage in pregnancy

- Menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal atrophy

- Hormone therapy for hypoestrogenism (e.g., gonadal dysgenesis, premature ovarian failure, and after oophorectomy)

- Postpartum lactation suppression to prevent or reverse breast engorgement

- Gonorrheal vaginitis (discontinued following the introduction of the antibiotic penicillin)

- Prostate cancer and breast cancer

- Prevention of tall stature in tall adolescent girls

- Treatment of acne in girls and women

- As an emergency postcoital contraceptive

- As a means of chemical castration for hypersexuality and paraphilias in men and sex offenders

- Prevention of the testosterone flare at the start of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH agonist) therapy

- Feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women

DES was used at a dosage of 0.2 to 0.5 mg/day in menopausal hormone therapy.

Interest in the use of DES to treat prostate cancer continues today. However, use of bioidentical parenteral estrogens like polyestradiol phosphate has been advocated in favor of oral synthetic estrogens like DES due to their much lower risk of cardiovascular toxicity. In addition to prostate cancer, some interest in the use of DES to treat breast cancer continues today as well. However, similarly to the case of prostate cancer, arguments have been made for the use of bioidentical estrogens like estradiol instead of DES for breast cancer.

Oral DES at 0.25 to 0.5 mg/day is effective in the treatment of hot flashes in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer.

Although DES was used to support pregnancy, it was later found not to be effective for this use and to actually be harmful.

Side effects

At more than 1 mg/day, DES is associated with high rates of side effects including nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, headache, and bloating (incidence of 15–50%).

Breast changes and feminization

The pigmentation of the breast areolae are often very dark and almost black with DES therapy. The pigmentation that occurs with synthetic estrogens such as DES is much greater than with natural estrogens such as estradiol. The mechanism of the difference is unknown.Progestogens like hydroxyprogesterone caproate have been reported to reduce the nipple hyperpigmentation induced by high-dose estrogen therapy.

In men treated with it for prostate cancer, DES has been found to produce high rates of gynecomastia (breast development) of 41 to 77%.

Blood clots and cardiovascular issues

In studies of DES as a form of high-dose estrogen therapy for those with prostate cancer, it has been associated with considerable cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The risk is dose-dependent. A dosage of 5 mg/day DES has been associated with a 36% increase in non-cancer-related (mostly cardiovascular) deaths. In addition, there is an up to 15% incidence of venous thromboembolism. A 3 mg/day dosage of DES has been associated with an incidence of thromboembolism of 9.6 to 17%, with an incidence of cardiovascular complications of 33.3%. A lower dosage of 1 mg/day DES has been associated with a rate of death due to cardiovascular events of 14.8% (relative to 8.3% for orchiectomy alone).

Other long-term effects

DES has been linked to a variety of long-term adverse effects, such as increased risk of

- vaginal clear-cell adenocarcinoma

- vaginal adenosis

- T-shaped uterus

- uterine fibroids

- cervical weakness

- breast cancer

- infertility

- hypogonadism

- intersexual gestational defects

- depression,

- and others,

in women who were treated with it during pregnancy, and/or in their offspring.

A comprehensive animal study in 1993 found a plethora of adverse effects from DES such as (but not limited to)

- genotoxicity (due to quinone metabolite)

- teratogenicity

- penile and testicular hypoplasia

- cryptorchidism (in rats and rhesus monkeys),

- liver and renal cancer (in hamsters), ovarian papillary carcinoma (in canines), and

- malignant uterine mesothelioma (in squirrel monkeys). Evidence was also found linking ADHD to F2 generations, demonstrating that there is at least some neurological and transgenerational effects in addition to the carcinogenic.

Rodent studies reveal female reproductive tract cancers and abnormalities reaching to the F2 generation, and there is evidence of adverse effects such as irregular menstrual cycles intersexual in grandchildren of DES mothers. Additionally, evidence also points to transgenerational effects in F2 sons, such as hypospadias. At this time however, the extent of DES transgenerational effects in humans is not fully understood.

Overdose

DES has been assessed in the past in clinical studies at extremely high doses of as much as 1,500 to 5,000 mg/day.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Estrogenic activity

DES is an estrogen; specifically, it is a highly potent full agonist of both of the estrogen receptors (ERs). It has approximately 468% and 295% of the affinity of estradiol at the ERα and ERβ, respectively. However, EC50 values of 0.18 nM and 0.06 nM of DES for the ERα and ERβ, respectively, have been reported, suggesting, in spite of its binding affinity for the two receptors, several-fold preference for activation of the ERβ over the ERα. In addition to the nuclear ERs, DES is an agonist of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), albeit with relatively low affinity (~1,000 nM). DES produces all of the same biological effects attributed to natural estrogens like estradiol. This includes effects in the uterus, vagina, mammary glands, pituitary gland, and other tissues.

A dosage of 1 mg/day DES is approximately equivalent to a dosage of 50 µg/day ethinylestradiol in terms of systemic estrogenic potency. Similarly to ethinylestradiol, DES shows a marked and disproportionately strong effect on liver protein synthesis. Whereas its systemic estrogenic potency was about 3.8-fold of that of estropipate (piperazine estrone sulfate), which has similar potency to micronized estradiol, the hepatic estrogenic potency of DES was 28-fold that of estropipate (or about 7.5-fold stronger potency for a dosage with equivalent systemic estrogenic effect).

DES has at least three mechanisms of action in the treatment of prostate cancer. It suppresses gonadal androgen production and hence circulating androgen levels due to its antigonadotropic effects; it stimulates hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) production, thereby increasing circulating levels of SHBG and decreasing the free fraction of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the circulation; and it may have direct cytotoxic effects in the testes and prostate gland. DES has also been found to decrease DNA synthesis at high doses.

DES is a long-acting estrogen, with a nuclear retention of around 24 hours.

| Estrogen | HF | VE | UCa | FSH | LH | HDL-C | SHBG | CBG | AGT | Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Estrone | ? | ? | ? | 0.3 | 0.3 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Estriol | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ? | ? | ? | 0.67 |

| Estrone sulfate | ? | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5–0.7 | 1.4–1.5 | 0.56–1.7 |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.1–1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0–3.2 | 1.3–1.5 | 5.0 | 1.3–4.5 |

| Equilin sulfate | ? | ? | 1.0 | ? | ? | 6.0 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 7.5 | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | 120 | 150 | 400 | 60–150 | 100 | 400 | 500–600 | 500–600 | 350 | 2.9–5.0 |

| Diethylstilbestrol | ? | ? | ? | 2.9–3.4 | ? | ? | 26–28 | 25–37 | 20 | 5.7–7.5 |

|

Sources and footnotes

Notes: Values are ratios, with estradiol as standard (i.e., 1.0). Abbreviations: HF = Clinical relief of hot flashes. VE = Increased proliferation of vaginal epithelium. UCa = Decrease in UCa. FSH = Suppression of FSH levels. LH = Suppression of LH levels. HDL-C, SHBG, CBG, and AGT = Increase in the serum levels of these liver proteins. Liver = Ratio of liver estrogenic effects to general/systemic estrogenic effects (hot flashes/gonadotropins). Sources: See template.

| ||||||||||

| Compound | Dosage for specific uses (mg usually) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETD | EPD | MSD | MSD | OID | TSD | ||

| Estradiol (non-micron.) | 30 | ≥120–300 | 120 | 6 | - | - | |

| Estradiol (micronized) | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | >5 | >8 | |

| Estradiol valerate | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | - | >8 | |

| Estradiol benzoate | - | 60–140 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estriol | ≥20 | 120–150 | 28–126 | 1–6 | >5 | - | |

| Estriol succinate | - | 140–150 | 28–126 | 2–6 | - | - | |

| Estrone sulfate | 12 | 60 | 42 | 2 | - | - | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 5–12 | 60–80 | 8.4–25 | 0.625–1.25 | >3.75 | 7.5 | |

| Ethinylestradiol | 200 μg | 1–2 | 280 μg | 20–40 μg | 100 μg | 100 μg | |

| Mestranol | 300 μg | 1.5–3.0 | 300–600 μg | 25–30 μg | >80 μg | - | |

| Quinestrol | 300 μg | 2–4 | 500 μg | 25–50 μg | - | - | |

| Methylestradiol | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diethylstilbestrol | 2.5 | 20–30 | 11 | 0.5–2.0 | >5 | 3 | |

| DES dipropionate | - | 15–30 | - | - | - | - | |

| Dienestrol | 5 | 30–40 | 42 | 0.5–4.0 | - | - | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | 3–5 | 30–60 | - | - | - | - | |

| Hexestrol | - | 70–110 | - | - | - | - | |

| Chlorotrianisene | - | >100 | - | - | >48 | - | |

| Methallenestril | - | 400 | - | - | - | - | |

|

Sources and footnotes:

| |||||||

| Estrogen | Form | Major brand name(s) | EPD (14 days) | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethylstilbestrol (DES) | Oil solution | Metestrol | 20 mg | 1 mg ≈ 2–3 days; 3 mg ≈ 3 days | |

| Diethylstilbestrol dipropionate | Oil solution | Cyren B | 12.5–15 mg | 2.5 mg ≈ 5 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | ? | 5 mg | ? mg = 21–28 days | ||

| Dimestrol (DES dimethyl ether) | Oil solution | Depot-Cyren, Depot-Oestromon, Retalon Retard | 20–40 mg | ? | |

| Fosfestrol (DES diphosphate)a | Aqueous solution | Honvan | ? | <1 day | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | Aqueous suspension | Farmacyrol-Kristallsuspension | 50 mg | ? | |

| Hexestrol dipropionate | Oil solution | Hormoestrol, Retalon Oleosum | 25 mg | ? | |

| Hexestrol diphosphatea | Aqueous solution | Cytostesin, Pharmestrin, Retalon Aquosum | ? | Very short | |

| Note: All by intramuscular injection unless otherwise noted. Footnotes: a = By intravenous injection. Sources: See template. | |||||

Antigonadotropic effects

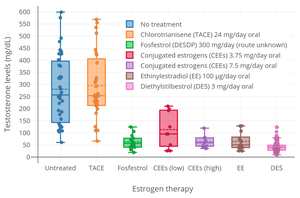

Due to its estrogenic activity, DES has antigonadotropic effects. That is, it exerts negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (HPG axis), suppresses the secretion of the gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and suppresses sex hormone production as well as gamete production or maturation in the gonads. A study of ovulation inhibition found that 5 mg/day oral DES was 92% effective, with ovulation occurring in only a single cycle. DES consistently suppresses testosterone levels in men into the castrate range (<50 ng/dL) within 1 to 2 weeks at doses of 3 mg/day and above. Conversely, a dosage of 1 mg/day DES is unable to fully suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range in men, which instead often stabilize at just above castrate levels (>50 ng/dL). However, it has also been reported that 1 mg/day DES results in approximately 50% suppression of testosterone levels, albeit with wide interindividual variability. It has been said that doses of DES of less than 1 mg/day have no effect on testosterone levels. However, the addition of an "extremely low" dosage of 0.1 mg/day DES to cyproterone acetate has been found to result in a synergistic antigonadotropic effect and to suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range in men. DES at 3 mg/day has similar testosterone suppression to a dose of 300 mg/day, suggesting that suppression of testosterone levels is maximal by 3 mg/day.

Other activities

In addition to the ERs, an in vitro study found that DES also possesses activity, albeit relatively weak, at a variety of other steroid hormone receptors. Whereas the study found EC50 values of 0.18 nM and 0.06 nM of DES for the ERα and ERβ, respectively, the medication showed significant glucocorticoid activity at a concentration of 1 μM that surpassed that of 0.1 nM dexamethasone, as well as significant antagonism of the androgen, progesterone, and mineralocorticoid receptors (75%, 85%, and 50% inhibition of positive control stimulation, respectively, all at a concentration of 1 μM). It also showed approximately 25% inhibition of the activation of PPARγ and LXRα at a concentration of 10 μM. The researchers stated that, to the best of their knowledge, they were the first to report such actions of DES, and hypothesized that these actions could be involved in the clinical effects of DES, for instance, in prostate cancer (notably in which particularly high dosages of DES are employed). However, they also noted that the importance of the activities requires further study in animal models at pharmacologically relevant doses.

DES has been identified as an antagonist of all three isotypes of the estrogen-related receptors (ERRs), the ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ. Half-maximal inhibition occurs at a concentration of about 1 μM.

Pharmacokinetics

DES is well-absorbed with oral administration. With an oral dosage of 1 mg/day DES, plasma levels of DES at 20 hours following the last dose ranged between 0.9 and 1.9 ng/mL (3.4 to 7.1 nmol/L).Sublingual administration of DES appears to have about the same estrogenic potency of oral DES in women.Intrauterine DES has been studied for the treatment of uterine hypoplasia. Oral DES is thought to have about 17 to 50% of the clinical estrogenic potency of DES by injection.

The distribution half-life of DES is 80 minutes. It has no affinity for SHBG or corticosteroid-binding globulin, and hence is not bound to these proteins in the circulation. The plasma protein binding of DES is greater than 95%.

Hydroxylation of the aromatic rings of DES and subsequent conjugation of the ethyl side chains accounts for 80 to 90% of DES metabolism, while oxidation accounts for the remaining 10 to 20% and is dominated by conjugation reactions. Conjugation of DES consists of glucuronidation, while oxidation includes dehydrogenation into (Z,Z)-dienestrol. The medication is also known to produce paroxypropione as a metabolite. DES produces transient quinone-like reactive intermediates that cause cellular and genetic damage, which may help to explain the known carcinogenic effects of DES in humans. However, other research indicates that the toxic effects of DES may simply be due to overactivation of the ERs. In contrast to estradiol, the hydroxyl groups of DES do not undergo oxidation into an estrone-like equivalent.

The elimination half-life of DES is 24 hours. The metabolites of DES are excreted in urine and feces.

Chemistry

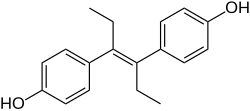

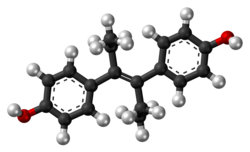

DES belongs to the stilbestrol (4,4'-dihydroxystilbene) group of compounds. It is a nonsteroidal open-ring analogue of the steroidal estrogen estradiol. DES can be prepared from anethole, which also happens to be weakly estrogenic. Anethole was demethylated to form anol and anol then spontaneously dimerized into dianol and hexestrol, with DES subsequently being synthesized via structural modification of hexestrol. As shown by X-ray crystallography, the molecular dimensions of DES are almost identical to those of estradiol, particularly in regards to the distance between the terminal hydroxyl groups.

History

Synthesis

DES was first synthesized in early 1938 by Leon Golberg, then a graduate student of Sir Robert Robinson at the Dyson Perrins Laboratory at the University of Oxford. Golberg's research was based on work by Wilfrid Lawson at the Courtauld Institute of Biochemistry, (led by Sir Edward Charles Dodds at Middlesex Hospital Medical School now part of University College London). A report of its synthesis was published in Nature on 5 February 1938.

DES research was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), which had a policy against patenting drugs discovered using public funds. Because it was not patented, DES was produced by more than 200 pharmaceutical and chemical companies worldwide.

Clinical use

DES was first marketed for medical use in 1939. It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on September 19, 1941, in tablets up to 5 mg for four indications: gonorrheal vaginitis, atrophic vaginitis, menopausal symptoms, and postpartum lactation suppression to prevent breast engorgement. The gonorrheal vaginitis indication was dropped when the antibiotic penicillin became available. From its very inception, the drug was highly controversial.

In 1941, Charles Huggins and Clarence Hodges at the University of Chicago found estradiol benzoate and DES to be the first effective drugs for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. DES was the first cancer drug.

Orchiectomy or DES or both were the standard initial treatment for symptomatic advanced prostate cancer for over 40 years, until the GnRH agonist leuprorelin was found to have efficacy similar to DES without estrogenic effects and was approved in 1985.

From the 1940s until the late 1980s, DES was FDA-approved as estrogen replacement therapy for estrogen deficiency states such as ovarian dysgenesis, premature ovarian failure, and after oophorectomy.

In the 1940s, DES was used off-label to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with a history of miscarriage. On July 1, 1947, the FDA approved the use of DES for this indication. The first such approval was granted to Bristol-Myers Squibb, allowing use of 25 mg (and later 100 mg) tablets of DES during pregnancy. Approvals were granted to other pharmaceutical companies later in the same year. The recommended regimen started at 5 mg per day in the seventh and eighth weeks of pregnancy (from first day of last menstrual period), increased every other week by 5 mg per day through the 14th week, and then increased every week by 5 mg per day from 25 mg per day in the 15th week to 125 mg per day in the 35th week of pregnancy. DES was originally considered effective and safe for both the pregnant woman and the developing baby. It was aggressively marketed and routinely prescribed. Sales peaked in 1953.

In the early 1950s, a double-blind clinical trial at the University of Chicago assessed pregnancy outcomes in women who were assigned to either receive or not receive DES. The study showed no benefit of taking DES during pregnancy; adverse pregnancy outcomes were not reduced in the women who were given DES. By the late 1960s, six of seven leading textbooks of obstetrics said DES was ineffective at preventing miscarriage.

Despite an absence of evidence supporting the use of DES to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes, DES continued to be given to pregnant women through the 1960s. In 1971, a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a probable link between DES and vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma in girls and young women who had been exposed to this drug in utero. Later in the same year, the FDA sent an FDA Drug Bulletin to all U.S. physicians advising against the use of DES in pregnant women. The FDA also removed prevention of miscarriage as an indication for DES use and added pregnancy as a contraindication for DES use. On February 5, 1975, the FDA ordered 25 mg and 100 mg tablets of DES withdrawn, effective February 18, 1975. The number of persons exposed to DES during pregnancy or in utero during the period of 1940 to 1971 is unknown, but may be as high as 2 million in the United States. DES was also used in other countries, most notably France, the Netherlands, and Great Britain.

From the 1950s through the beginning of the 1970s, DES was prescribed to prepubescent girls to begin puberty and thus stop growth by closing growth plates in the bones. Despite its clear link to cancer, doctors continued to recommend the hormone for "excess height".

In 1960, DES was found to be more effective than androgens in the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. DES was the hormonal treatment of choice for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women until 1977, when the FDA approved tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator with efficacy similar to DES but fewer side effects.

Several sources from medical literature in the 1970s and 1980s indicate that DES was used as a component of hormone therapy for transgender women.

In 1973, in an attempt to restrict off-label use of DES as a postcoital contraceptive (which had become prevalent at many university health services following publication of an influential study in 1971 in JAMA) to emergency situations such as rape, an FDA Drug Bulletin was sent to all U.S. physicians and pharmacists that said the FDA had approved, under restricted conditions, postcoital contraceptive use of DES.

In 1975, the FDA said it had not actually given (and never did give) approval to any manufacturer to market DES as a postcoital contraceptive, but would approve that indication for emergency situations such as rape or incest if a manufacturer provided patient labeling and special packaging as set out in a FDA final rule published in 1975. To discourage off-label use of DES as a postcoital contraceptive, the FDA in 1975 removed DES 25 mg tablets from the market and ordered the labeling of lower doses (5 mg and lower) of DES still approved for other indications changed to state: "This drug product should not be used as a postcoital contraceptive" in block capital letters on the first line of the physician prescribing information package insert and in a prominent and conspicuous location of the container and carton label. In the 1980s, off-label use of the Yuzpe regimen of certain regular combined oral contraceptive pills superseded off-label use of DES as a postcoital contraceptive.

In 1978, the FDA removed postpartum lactation suppression to prevent breast engorgement from their approved indications for DES and other estrogens. In the 1990s, the only approved indications for DES were treatment of advanced prostate cancer and treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. The last remaining U.S. manufacturer of DES, Eli Lilly, stopped making and marketing it in 1997.

Trials

Diethylstilbestrol has been used countless times in studies on rats. Once it was discovered that DES was causing vaginal cancer, experiments began on both male and female rats. Many of these male rats were injected with DES while other male rats were injected with olive oil, and they were considered the control group. Each group received the same dosage on the same days, and the researchers performed light microscopy, electron microscopy, and confocal laser microscopy. With both the electron and confocal laser microscopy, it was prevalent that the Sertoli cells, which are somatic cells where spermatids develop in the testes, were formed 35 days later in the rats who were injected with Diethylstilbestrol compared to the rats in the control group. Proceeding the completion of the trial, it was understood that rats of older age who were injected with DES experienced delay in sertoli cell maturation, underdeveloped epididymides, and drastic decrease in weight compared to its counterparts.

The female rats used were inbred and most of them were given DES combined in their food. These rats were divided into three groups, one group who received no diethylstilbestrol, one group who had DES mixed into their diet, and the third group who had DES administered into their diet after day 13 of being pregnant. Some rats who were given DES unfortunately died before delivering their pup. The group that received DES in their food for 13 days while being pregnant resulted in early abortion and delivery failure. These outcomes showed that DES had a detrimental effect on pregnancy when administered as often as it was. Providing the dosing of diethylstilbestrol later in the pregnancy term also made visible the occurrence of abortions among the rats. Overall, any interaction with DES in female rats concluded in the rats' experiencing abortions, improper fetal growth, and the increase in sterility.

A review of people who had been treated or exposed to DES was done to find out how long-term effects would show. People for a long time had been treated during their pregnancy with DES and there have been known to be toxic and adverse effects to the hormone therapy. "Exposure to DES has been associated with an increased risk for breast cancer in DES mothers (relative risk, <2.0) and with a lifetime risk of clear-cell cervicovaginal cancer in DES daughters of 1/1000 to 1/10 000." Side effects of DES are proving to be long-term as it can cause increased risks to cancer after use. There will be continued work to see how far the adverse effects of DES will go after previous therapy as many women had used this during pregnancy and there is a long line to see how it will effect offspring and the mothers longer-term.

Regulations

In 1938, the ability to test the safety of DES on animals was first obtained by the FDA. The results from the preliminary tests showed that DES harmed the reproductive systems of animals. The application of these results to humans could not be determined, so the FDA could not act in a regulatory manner.

New Drug Applications for DES approval were withdrawn in 1940 in a decision made by the FDA based on scientific uncertainty. However, this decision resulted in significant political pressure, so the FDA came to a compromise. The compromise meant that DES would be available only by prescription and would have to have warnings about its effects on the bottle, but the warning was dropped in 1945. In 1947, DES finally gained FDA approval for prescription to pregnant women who had diabetes as a method of preventing miscarriages. This led to the widespread prescription of DES to all pregnant women.

In 1971, the FDA recommended against the prescription of DES to pregnant women. As a result, DES then began to see a withdraw from the US market starting in 1972 and in the European market starting in 1978, but the FDA still did not withdraw its approval for the use of DES in humans.

DES was classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. After classification as a carcinogen, DES had its FDA approval withdrawn in 2000. DES is currently only in use for veterinary practices and in research trials as allowed by the FDA.

Medical ethics

Medical Ethics in regard to the approval and use of Diethylstilbestrol have been dismissed because of the actions of the FDA and pharmaceutical companies that were making DES at the time of its use. The Vice President of the American Drug Manufacturers Association, Carson Frailey, was employed by drug companies creating DES in order to help get it approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Nancy Langston, the author of The Retreat from Precaution: Regulating Diethylstilbestrol (DES), Endocrine Disruptors, and Environmental Health, states that "Frailey persuaded fifty-four doctors from around the country to write to the FDA, describing their clinical experiences with a total of more than five thousand patients. Only four of these fifty-four doctors felt that DES should not be approved, and the result was that, against the concerns of many of the FDA medical staff, the FDA's drug chief Theodore Klumpp recommended that the FDA approve DES." This excerpt describes how DES was unethically approved and shows that the motivation behind its approval was for the benefit of drug companies rather than the people who were going to use the drug. This approval of DES violates the values of medical ethics, autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice as there was little thought put into how DES would affect its users. The decisions made by the FDA leaders to approve DES without further study and convince doctors to dissimulate their opinions on the use of DES is unethical. Once DES was approved for public consumption the "warnings [for DES were] made available only on a separate circular that patients would not see. Doctors could get this warning circular only by writing to the drug companies and requesting it. Letters between companies and FDA regulators reveal that both groups feared that if a woman ever saw how many potential risks DES might present, she might refuse to take the drug—or else she might sue the company and the prescribing doctors if she did get cancer or liver damage after taking the drug." Women were not informed about the possible effects of DES because doctors and FDA regulators were afraid DES would fail and never be approved costing the drug companies millions of dollars. The act of distributing potentially dangerous medicine to patients regardless of the effect and harm it may do solely for monetary gain is unethical.

Lawsuits

In the 1970s, the negative publicity surrounding the discovery of DES's long-term effects resulted in a huge wave of lawsuits in the United States against its manufacturers. These culminated in a landmark 1980 decision of the Supreme Court of California, Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories, in which the court imposed a rebuttable presumption of market share liability upon all DES manufacturers, proportional to their share of the market at the time the drug was consumed by the mother of a particular plaintiff.

Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical company manufacturing DES, and the University of Chicago, had an action filed against them in regard to clinical trials from the 1950s. Three women filed the claim that their daughters had developments of abnormal cervical cellular formations as well as reproductive abnormalities in themselves and their sons. The plaintiffs had asked the courts to certify their case as a class action but were declined by the courts. However, the courts issued an opinion that their case had merit. The court held that Eli Lilly had a duty to notify about the risks of DES once they became aware of them or should have become aware of them. Under Illinois tort law, for the plaintiffs to recover under theories of breach of duty to warn and strict liability, the plaintiffs must have alleged injury to themselves. Ultimately, under their claims of breach of duty to warn and strict liability due to the plaintiffs citing risk of physical injury to others, not physical injury to themselves, the case was dismissed by the courts. Although the case was not certified as class action and their claims of breach of duty to warn and strict liability was dismissed, the courts did not dismiss the battery allegations. The issue was then to determine whether the University of Chicago had committed battery against these women but the case was settled before trial. Part of the settlement agreement for this case, Mink v. University of Chicago, attorneys for the plaintiffs negotiated for the university to provide free medical exams for all offspring exposed to DES in utero during the 1950 experiments as well as treat the daughters of any women involved who develop DES-associated vaginal or cervical cancer.

As of February 1991, there were over a thousand pending legal actions against DES manufacturers. There are over 300 companies that manufactured DES according to the same formula and the largest barrier to recovery is determining which manufacturer supplied the drug in each particular case. Many of the successful cases have relied on joint or several parties holding liability.

A lawsuit was filed in Boston Federal Court by 53 DES daughters who say their breast cancers were the result of DES being prescribed to their mothers while pregnant with them. Their cases survived a Daubert hearing. In 2013, the Fecho sisters who initiated the breast cancer/DES link litigation agreed to an undisclosed settlement amount on the second day of trial. The remaining litigants have received various settlements.

The advocacy group DES Action USA helped provide information and support for DES-exposed persons engaged in lawsuits.

Society and culture

Alan Turing, the ground-breaking cryptographer, founder of computing science and programmable computers, who also proposed the actual theoretical model of biological morphogenesis, was forced onto this medication to induce chemical castration as a punitive and discredited "treatment" for homosexual behaviour, shortly before he died in ambiguous circumstances.

At least on one occasion in New Zealand in the early 1960s, Diethylstilbestrol was prescribed for the treatment of homosexuality.

James Herriot describes a case regarding treating a small dog's testicular Sertoli cell tumor in his 1974 book All Things Bright and Beautiful. Herriot decided to prescribe a high dose of the new drug Stilboestrol for the recurring tumor, with the amusing side effect that the male dog became "attractive to other male dogs", who followed the terrier around the village for a few weeks. Herriot comments in the story that he knew "The new drug was said to have a feminising effect, but surely not to that extent."

Veterinary use

Canine incontinence

DES has been very successful in treating female canine incontinence stemming from poor sphincter control. It is still available from compounding pharmacies, and at the low (1 mg) dose, does not have the carcinogenic properties that were so problematic in humans. It is generally administered once a day for seven to ten days and then once every week as needed.

Livestock growth promotion

The greatest usage of DES was in the livestock industry, used to improve feed conversion in beef and poultry. During the 1960s, DES was used as a growth hormone in the beef and poultry industries. It was later found to cause cancer by 1971, but was not phased out until 1979. Although DES was discovered to be harmful to humans, its veterinary use was not immediately halted. As of 2011, DES was still being used as a growth promoter in terrestrial livestock or fish in some parts of the world including China.

Further reading

External links

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) and Cancer National Cancer Institute

- DES Update from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DES Action USA national consumer organization providing comprehensive information for DES-exposed individuals

- DES Booklets from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (c. 1980)

- DES Follow-up Study Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine National Cancer Institute's longterm study of DES-exposed persons (including the DES-AD Project)

- University of Chicago DES Registry of patients with CCA (clear cell adenocarcinoma) of the vagina and/or cervix

- DES Diethylstilbestrol Provides resources and social media links for general DES awareness

| ER |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPER |

|

||||||

| ERRα |

|

|---|---|

| ERRβ |

|

| ERRγ |

|

| |