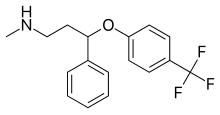

Fluoxetine

| |

Fluoxetine (top),

(R)-fluoxetine (left), (S)-fluoxetine (right) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

/fluˈɒksətiːn/ floo-OKS-ə-teen |

| Trade names | Prozac, Sarafem, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689006 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Addiction liability |

None |

| Routes of administration |

By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–80% |

| Protein binding | 94–95% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP2D6-mediated) |

| Metabolites | Norfluoxetine, desmethylfluoxetine |

| Elimination half-life | 1–3 days (acute) 4–6 days (chronic) |

| Excretion | Urine (80%), faeces (15%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.370 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H18F3NO |

| Molar mass | 309.332 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 179 to 182 °C (354 to 360 °F) |

| Boiling point | 395 °C (743 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 14 |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Fluoxetine, sold under the brand name Prozac, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It is used for the treatment of major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. It is also approved for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and children 8 years of age and over. It has also been used to treat premature ejaculation. Fluoxetine is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include indigestion, trouble sleeping, sexual dysfunction, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, dry mouth, and rash. Serious side effects include serotonin syndrome, mania, seizures, an increased risk of suicidal behavior in people under 25 years old, and an increased risk of bleeding.Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is less likely to occur with fluoxetine than with other antidepressants, but it still happens in many cases. Fluoxetine taken during pregnancy is associated with significant increase in congenital heart defects in the newborns. It has been suggested that fluoxetine therapy may be continued during breastfeeding if it was used during pregnancy or if other antidepressants were ineffective.

Fluoxetine was discovered by Eli Lilly and Company in 1972, and entered medical use in 1986. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. In 2020, it was the 25th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 23 million prescriptions. Lilly also markets fluoxetine in a fixed-dose combination with olanzapine as olanzapine/fluoxetine (Symbyax).

Medical uses

Fluoxetine is frequently used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and trichotillomania. It has also been used for cataplexy, obesity, and alcohol dependence, as well as binge eating disorder. Fluoxetine seems to be ineffective for social anxiety disorder. Studies do not support a benefit in children with autism, though there is tentative evidence for its benefit in adult autism. Fluoxetine together with fluvoxamine has shown some initial promise as a potential treatment for reducing COVID-19 severity if given early.

Depression

Fluoxetine is approved for the treatment of major depression in children and adults. Meta-analyses of trials in adults conclude that fluoxetine modestly outperforms placebo. Fluoxetine may be less effective than other antidepressants, but has high acceptability.

For children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe depressive disorder, fluoxetine seems to be the best treatment (either with or without cognitive behavioural therapy, although fluoxetine alone does not appear to be superior to CBT alone) but more research is needed to be certain, as effect sizes are small and the existing evidence is of dubious quality. A 2022 systematic review of the two original blinded-control trials used to approve the use of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression found that both of the control trials were severely flawed, and did not demonstrate the efficacy of the medication.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Fluoxetine is effective in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) for adults. It is also effective for treating OCD in children and adolescents. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry state that SSRIs, including fluoxetine, should be used as first-line therapy in children, along with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for the treatment of moderate to severe OCD.

Panic disorder

The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder was demonstrated in two 12-week randomized multicenter phase III clinical trials that enrolled patients diagnosed with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. In the first trial, 42% of subjects in the fluoxetine-treated arm were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 28% in the placebo arm. In the second trial, 62% of fluoxetine treated patients were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 44% in the placebo arm.

Bulimia nervosa

A 2011 systematic review discussed seven trials which compared fluoxetine to a placebo in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, six of which found a statistically significant reduction in symptoms such as vomiting and binge eating. However, no difference was observed between treatment arms when fluoxetine and psychotherapy were compared to psychotherapy alone.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Fluoxetine is used to treat premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a condition where individuals have affective and somatic symptoms monthly during the luteal phase of menstruation. Taking fluoxetine 20 mg/d can be effective in treating PMDD, though doses of 10 mg/d have also been prescribed effectively.

Impulsive aggression

Fluoxetine is considered a first-line medication for the treatment of impulsive aggression of low intensity. Fluoxetine reduced low intensity aggressive behavior in patients in intermittent aggressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. Fluoxetine also reduced acts of domestic violence in alcoholics with a history of such behavior.

Obesity and overweight adults

In 2019 a systematic review compared the effects on weight of various doses of fluoxetine (60mg/d, 40 mg/d, 20mg/d, 10mg/d) in obese and overweight adults. When compared to placebo, fluoxetine all dosages of fluoxetine appeared to contribute to weight loss but lead to increased risk of experiencing side effects such as dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, insomnia and nausea during period of treatment. However, these conclusions were from low certainty evidence. When comparing, in the same review, the effects of fluoxetine on weight of obese and overweight adults, to other anti-obesity agents, omega-3 gel and not receiving a treatment, the authors could not reach conclusive results due to poor quality of evidence.

Special populations

In children and adolescents, fluoxetine is the antidepressant of choice due to tentative evidence favoring its efficacy and tolerability. Evidence supporting an increased risk of major fetal malformations resulting from fluoxetine exposure is limited, although the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) of the United Kingdom has warned prescribers and patients of the potential for fluoxetine exposure in the first trimester (during organogenesis, formation of the fetal organs) to cause a slight increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations in the newborn. Furthermore, an association between fluoxetine use during the first trimester and an increased risk of minor fetal malformations was observed in one study.

However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies – published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada – concluded, "the apparent increased risk of fetal cardiac malformations associated with maternal use of fluoxetine has recently been shown also in depressed women who deferred SSRI therapy in pregnancy, and therefore most probably reflects an ascertainment bias. Overall, women who are treated with fluoxetine during the first trimester of pregnancy do not appear to have an increased risk of major fetal malformations."

Per the FDA, infants exposed to SSRIs in late pregnancy may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Limited data support this risk, but the FDA recommends physicians consider tapering SSRIs such as fluoxetine during the third trimester. A 2009 review recommended against fluoxetine as a first-line SSRI during lactation, stating, "Fluoxetine should be viewed as a less-preferred SSRI for breastfeeding mothers, particularly with newborn infants, and in those mothers who consumed fluoxetine during gestation."Sertraline is often the preferred SSRI during pregnancy due to the relatively minimal fetal exposure observed and its safety profile while breastfeeding.

Adverse effects

Side effects observed in fluoxetine-treated persons in clinical trials with an incidence >5% and at least twice as common in fluoxetine-treated persons compared to those who received a placebo pill include abnormal dreams, abnormal ejaculation, anorexia, anxiety, asthenia, diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, dyspepsia, fatigue, flu syndrome, impotence, insomnia, decreased libido, nausea, nervousness, pharyngitis, rash, sinusitis, somnolence, sweating, tremor, vasodilation, and yawning. Fluoxetine is considered the most stimulating of the SSRIs (that is, it is most prone to causing insomnia and agitation). It also appears to be the most prone of the SSRIs for producing dermatologic reactions (e.g. urticaria (hives), rash, itchiness, etc.).

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction, including loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, lack of vaginal lubrication, and anorgasmia, are some of the most commonly encountered adverse effects of treatment with fluoxetine and other SSRIs. While early clinical trials suggested a relatively low rate of sexual dysfunction, more recent studies in which the investigator actively inquires about sexual problems suggest that the incidence is >70%.

On 11 June 2019, the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the European Medicines Agency concluded that there is a possible causal association between SSRI use and long-lasting sexual dysfunction that persists despite discontinuation of SSRI, including fluoxetine, and that the labels of these drugs should be updated to include a warning.

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

Fluoxetine's longer half-life makes it less common to develop antidepressant discontinuation syndrome following cessation of therapy, especially when compared with antidepressants with shorter half-lives such as paroxetine. Although gradual dose reductions are recommended with antidepressants with shorter half-lives, tapering may not be necessary with fluoxetine.

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including fluoxetine) is associated with shorter average duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points). There is 30–36% increase in congenital heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed fluoxetine during pregnancy, with fluoxetine use in the first trimester associated with 38–65% increase in septal heart defects.

Suicide

In October 2004, the FDA added a black box warning to all antidepressant drugs regarding use in children. In 2006, the FDA included adults aged 25 or younger. Statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts found a 2-fold increase of the suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group. The suicidality was slightly decreased for those older than 24, and statistically significantly lower in the 65 and older group. This analysis was criticized by Donald Klein, who noted that suicidality, that is suicidal ideation and behavior, is not necessarily a good surrogate marker for suicide, and it is still possible, while unproven, that antidepressants may prevent actual suicide while increasing suicidality. In February 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered an update to the warnings based on statistical evidence from twenty four trials in which the risk of such events increased from two percent to four percent relative to the placebo trials.

On 14 September 1989, Joseph T. Wesbecker killed eight people and injured twelve before committing suicide. His relatives and victims blamed his actions on the Prozac medication he had begun taking a month prior. The incident set off a chain of lawsuits and public outcries. Lawyers began using Prozac to justify the abnormal behaviors of their clients.Eli Lilly was accused of not doing enough to warn patients and doctors about the adverse effects, which it had described as "activation", years prior to the incident.

There is less data on fluoxetine than on antidepressants as a whole. In 2004, the FDA had to combine the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications to obtain statistically significant results. Considered separately, fluoxetine use in children increased the odds of suicidality by 50%, and in adults decreased the odds of suicidality by approximately 30%. A study published in May 2009 found that fluoxetine was more likely to increase overall suicidal behavior. 14.7% of the patients (n = 44) on fluoxetine had suicidal events, compared to 6.3% in the psychotherapy group and 8.4% from the combined treatment group. Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase in suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the children and adolescents on fluoxetine as compared to the ones on placebo. According to the MHRA data, fluoxetine did not change the rate of self-harm in adults and statistically significantly decreased suicidal ideation by 50%.

QT prolongation

Fluoxetine can affect the electrical currents that heart muscle cells use to coordinate their contraction, specifically the potassium currents Ito and IKs that repolarise the cardiac action potential. Under certain circumstances, this can lead to prolongation of the QT interval, a measurement made on an electrocardiogram reflecting how long it takes for the heart to electrically recharge after each heartbeat. When fluoxetine is taken alongside other drugs that prolong the QT interval, or by those with a susceptibility to long QT syndrome, there is a small risk of potentially lethal abnormal heart rhythms such as torsades de pointes. A study completed in 2011 found that fluoxetine does not alter the QT interval and has no clinically meaningful effects on the cardiac action potential.

Overdose

In overdose, most frequent adverse effects include:

|

Nervous system effects

|

Gastrointestinal effects

|

Other effects

|

Interactions

Contraindications include prior treatment (within the past 5–6 weeks, depending on the dose) with MAOIs such as phenelzine and tranylcypromine, due to the potential for serotonin syndrome. Its use should also be avoided in those with known hypersensitivities to fluoxetine or any of the other ingredients in the formulation used. Its use in those concurrently receiving pimozide or thioridazine is also advised against.

In case of short term administration of codeine for pain management, it is advised to monitor and adjust dosage. Codeine might not provide sufficient analgesia when Fluoxetine is co-administered. If opioid treatment is required, oxycodone use should be monitored since oxycodone is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system and fluoxetine and paroxetine are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 enzymes. This means combinations of codeine or oxycodone with fluoxetine antidepressant may lead to reduced analgesia.

In some cases, use of dextromethorphan-containing cold and cough medications with fluoxetine is advised against, due to fluoxetine increasing serotonin levels, as well as the fact that fluoxetine is a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, which causes dextromethorphan to not be metabolized at a normal rate, thus increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome and other potential side effects of dextromethorphan.

Patients who are taking NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements must be careful when taking fluoxetine or other SSRIs, as they can sometimes increase the blood-thinning effects of these medications.

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit many isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system that are involved in drug metabolism. Both are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 (which is also the chief enzyme responsible for their metabolism) and CYP2C19, and mild to moderate inhibitors of CYP2B6 and CYP2C9.In vivo, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine do not significantly affect the activity of CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. They also inhibit the activity of P-glycoprotein, a type of membrane transport protein that plays an important role in drug transport and metabolism and hence P-glycoprotein substrates such as loperamide may have their central effects potentiated. This extensive effect on the body's pathways for drug metabolism creates the potential for interactions with many commonly used drugs.

Its use should also be avoided in those receiving other serotonergic drugs such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, methamphetamine, amphetamine, MDMA, triptans, buspirone, ginseng, dextromethorphan (DXM), linezolid, tramadol, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and other SSRIs due to the potential for serotonin syndrome to develop as a result.

Fluoxetine may also increase the risk of opioid overdose in some instances, in part due to its inhibitory effect on cytochrome P-450. Similar to how fluoxetine can effect the metabolization of dextromethorphan, it may cause medications like oxycodone to not be metabolized at a normal rate, thus increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome as well as resulting in an increased concentration of oxycodone in the blood, which may lead to accidental overdose. A 2022 study which examined the health insurance claims of over 2 million Americans who began taking oxycodone while using SSRIs between 2000 and 2020, found that patients taking paroxetine or fluoxetine had a 23% higher risk of overdosing on oxycodone than those using other SSRIs.

There is also the potential for interaction with highly protein-bound drugs due to the potential for fluoxetine to displace said drugs from the plasma or vice versa hence increasing serum concentrations of either fluoxetine or the offending agent.

Pharmacology

| Molecular Target |

Fluoxetine | Norfluoxetine |

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 1 | 19 |

| NET | 660 | 2700 |

| DAT | 4180 | 420 |

| 5-HT2A | 119 ± 10 | 300 |

| 5-HT2B | 2514 | 5100 |

| 5-HT2C | 118 ± 11 | 91.2 |

| α1 | 3000 | 3900 |

| M1 | 870 | 1200 |

| M2 | 2700 | 4600 |

| M3 | 1000 | 760 |

| M4 | 2900 | 2600 |

| M5 | 2700 | 2200 |

| H1 | 3250 | 10000 |

| Entries with this color indicate a lower bound of the Ki value. | ||

Pharmacodynamics

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and does not appreciably inhibit norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake at therapeutic doses. It does, however, delay the reuptake of serotonin, resulting in serotonin persisting longer when it is released. Large doses in rats have been shown to induce a significant increase in synaptic norepinephrine and dopamine. Thus, dopamine and norepinephrine may contribute to the antidepressant action of fluoxetine in humans at supratherapeutic doses (60–80 mg). This effect may be mediated by 5HT2C receptors, which are inhibited by higher concentrations of fluoxetine.

Fluoxetine increases the concentration of circulating allopregnanolone, a potent GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator, in the brain.Norfluoxetine, a primary active metabolite of fluoxetine, produces a similar effect on allopregnanolone levels in the brains of mice. Additionally, both fluoxetine and norfluoxetine are such modulators themselves, actions which may be clinically-relevant.

In addition, fluoxetine has been found to act as an agonist of the σ1-receptor, with a potency greater than that of citalopram but less than that of fluvoxamine. However, the significance of this property is not fully clear. Fluoxetine also functions as a channel blocker of anoctamin 1, a calcium-activated chloride channel. A number of other ion channels, including nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and 5-HT3 receptors, are also known to be inhibited at similar concentrations.

Fluoxetine has been shown to inhibit acid sphingomyelinase, a key regulator of ceramide levels which derives ceramide from sphingomyelin.

Mechanism of action

While it is unclear how fluoxetine exerts its effect on mood, it has been suggested that fluoxetine elicits antidepressant effect by inhibiting serotonin reuptake in the synapse by binding to the reuptake pump on the neuronal membrane to increase serotonin availability and enhance neurotransmission. Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases. Norfluoxetine and desmethylfluoxetine are metabolites of fluoxetine and also act as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, increasing the duration of action of the drug.

Prolonged exposure to fluoxetine changes the expression of genes involved in myelination, a process that shapes brain connectivity and contributes to symptoms of psychiatric disorders. The regulation of genes involved with myelination is partially responsible for the long-term therapeutic benefits of chronic SSRI exposure.

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of fluoxetine is relatively high (72%), and peak plasma concentrations are reached in 6–8 hours. It is highly bound to plasma proteins, mostly albumin and α1-glycoprotein. Fluoxetine is metabolized in the liver by isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP2D6. The role of CYP2D6 in the metabolism of fluoxetine may be clinically important, as there is great genetic variability in the function of this enzyme among people. CYP2D6 is responsible for converting fluoxetine to its only active metabolite, norfluoxetine. Both drugs are also potent inhibitors of CYP2D6.

The extremely slow elimination of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine from the body distinguishes it from other antidepressants. With time, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit their own metabolism, so fluoxetine elimination half-life increases from 1 to 3 days, after a single dose, to 4 to 6 days, after long-term use. Similarly, the half-life of norfluoxetine is longer (16 days) after long-term use. Therefore, the concentration of the drug and its active metabolite in the blood continues to grow through the first few weeks of treatment, and their steady concentration in the blood is achieved only after four weeks. Moreover, the brain concentration of fluoxetine and its metabolites keeps increasing through at least the first five weeks of treatment. For major depressive disorder, while onset of antidepressant action may be felt as early as 1-2 weeks, the full benefit of the current dose a patient receives is not realized for at least a month following ingestion. For example, in one 6-week study, the median time to achieving consistent response was 29 days. Likewise, complete excretion of the drug may take several weeks. During the first week after treatment discontinuation, the brain concentration of fluoxetine decreases by only 50%, The blood level of norfluoxetine four weeks after treatment discontinuation is about 80% of the level registered by the end of the first treatment week, and, seven weeks after discontinuation, norfluoxetine is still detectable in the blood.

Measurement in body fluids

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine may be quantitated in blood, plasma or serum to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized person or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma fluoxetine concentrations are usually in a range of 50–500 μg/L in persons taking the drug for its antidepressant effects, 900–3000 μg/L in survivors of acute overdosage and 1000–7000 μg/L in victims of fatal overdosage. Norfluoxetine concentrations are approximately equal to those of the parent drug during chronic therapy, but may be substantially less following acute overdosage, since it requires at least 1–2 weeks for the metabolite to achieve equilibrium.

History

The work which eventually led to the discovery of fluoxetine began at Eli Lilly and Company in 1970 as a collaboration between Bryan Molloy and Robert Rathbun. It was known at that time that the antihistamine diphenhydramine shows some antidepressant-like properties. 3-Phenoxy-3-phenylpropylamine, a compound structurally similar to diphenhydramine, was taken as a starting point, and Molloy synthesized a series of dozens of its derivatives. Hoping to find a derivative inhibiting only serotonin reuptake, an Eli Lilly scientist, David T. Wong, proposed to retest the series for the in vitro reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. This test showed the compound later named fluoxetine to be the most potent and selective inhibitor of serotonin reuptake of the series. The first article about fluoxetine was published in 1974. A year later, it was given the official chemical name fluoxetine and the Eli Lilly and Company gave it the brand name Prozac. In February 1977, Dista Products Company, a division of Eli Lilly & Company, filed an Investigational New Drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for fluoxetine.

Fluoxetine appeared on the Belgian market in 1986. In the U.S., the FDA gave its final approval in December 1987, and a month later Eli Lilly began marketing Prozac; annual sales in the U.S. reached $350 million within a year. Worldwide sales eventually reached a peak of $2.6 billion a year.

Lilly tried several product line extension strategies, including extended release formulations and paying for clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and rebranding fluoxetine for that indication as "Sarafem" after it was approved by the FDA in 2000, following the recommendation of an advisory committee in 1999. The invention of using fluoxetine to treat PMDD was made by Richard Wurtman at MIT; the patent was licensed to his startup, Interneuron, which in turn sold it to Lilly.

To defend its Prozac revenue from generic competition, Lilly also fought a five-year, multimillion-dollar battle in court with the generic company Barr Pharmaceuticals to protect its patents on fluoxetine, and lost the cases for its line-extension patents, other than those for Sarafem, opening fluoxetine to generic manufacturers starting in 2001. When Lilly's patent expired in August 2001,generic drug competition decreased Lilly's sales of fluoxetine by 70% within two months.

In 2000 an investment bank had projected that annual sales of Sarafem could reach $250M/year. Sales of Sarafem reached about $85M/year in 2002, and in that year Lilly sold its assets connected with the drug for $295M to Galen Holdings, a small Irish pharmaceutical company specializing in dermatology and women's health that had a sales force tasked to gynecologists' offices; analysts found the deal sensible since the annual sales of Sarafem made a material financial difference to Galen, but not to Lilly.

Bringing Sarafem to market harmed Lilly's reputation in some quarters. The diagnostic category of PMDD was controversial since it was first proposed in 1987, and Lilly's role in retaining it in the appendix of the DSM-IV-TR, the discussions for which got under way in 1998, has been criticized. Lilly was criticized for inventing a disease in order to make money, and for not innovating but rather just seeking ways to continue making money from existing drugs. It was also criticized by the FDA and groups concerned with women's health for marketing Sarafem too aggressively when it was first launched; the campaign included a television commercial featuring a harried woman at the grocery store who asks herself if she has PMDD.

Society and culture

Prescription trends

In 2010, over 24.4 million prescriptions for generic fluoxetine were filled in the United States, making it the third-most prescribed antidepressant after sertraline and citalopram.

In 2011, 6 million prescriptions for fluoxetine were filled in the United Kingdom. Between 1998 and 2017, along with amitriptyline, it was the most commonly prescribed first antidepressant for adolescents aged 12-17 years in England.

Environmental effects

Fluoxetine has been detected in aquatic ecosystems, especially in North America. There is a growing body of research addressing the effects of fluoxetine (among other SSRIs) exposure on non-target aquatic species.

In 2003, one of the first studies addressed in detail the potential effects of fluoxetine on aquatic wildlife; this research concluded that exposure at environmental concentrations was of little risk to aquatic systems if a hazard quotient approach was applied to risk assessment. However, they also stated the need for further research addressing sub-lethal consequences of fluoxetine, specifically focusing on study species' sensitivity, behavioural responses, and endpoints modulated by the serotonin system.

Fluoxetine – similar to several other SSRIs – induces reproductive behavior in some shellfish at concentrations as low as 10-10M, or 30 parts per trillion.

Since 2003, a number of studies have reported fluoxetine-induced impacts on a number of behavioural and physiological endpoints, inducing antipredator behaviour, reproduction, and foraging at or below field-detected concentrations. However, a 2014 review on the ecotoxicology of fluoxetine concluded that, at that time, a consensus on the ability of environmentally realistic dosages to affect the behaviour of wildlife could not be reached. At environmentally realistic concentrations, fluoxetine alters insect emergence timing. Richmond et al., 2019 find that at low concentrations it accelerates emergence of Diptera, while at unusually high concentrations it has no discernable effect.

Several common plants are known to absorb fluoxetine. Several crops have been tested, and Redshaw et al. 2008 find that cauliflower absorbs large amounts into the stem and leaf but not the head or root. Wu et al. 2012 find that lettuce and spinach also absorb detectable amounts, while Carter et al. 2014 find that radish (Raphanus sativus), ryegrass (Lolium perenne) – and Wu et al. 2010 find that soybean (Glycine max) – absorb little. Wu tested all tissues of soybean and all showed only low concentrations. By contrast various Reinhold et al. 2010 find duckweeds have a high uptake of fluoxetine and show promise for bioremediation of contaminated water, especially Lemna minor and Landoltia punctata. Ecotoxicity for organisms involved in aquaculture is well documented. Fluoxetine affects both aquacultured invertebrates and vertebrates, and inhibits soil microbes including a large antibacterial effect. For applications of this see § Other uses.

Politics

During the 1990 campaign for Governor of Florida, it was disclosed that one of the candidates, Lawton Chiles, had depression and had resumed taking fluoxetine, leading his political opponents to question his fitness to serve as Governor.

American aircraft pilots

Beginning 5 April 2010, fluoxetine became one of four antidepressant drugs that the FAA permitted for pilots with authorization from an aviation medical examiner. The other permitted antidepressants are sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), and escitalopram (Lexapro). These four remain the only antidepressants permitted by FAA as of 2 December 2016.

Sertraline, citalopram and escitalopram are the only antidepressants permitted for EASA medical certification, as of January 2019.

Other uses

The antibacterial effect in described above (§ Environmental effects) could be applied against multiresistant biotypes in crop bacterial diseases and bacterial aquaculture diseases. In a glucocorticoid receptor-defective zebrafish mutant (Danio rerio) with reduced exploratory behavior, fluoxetine rescued the normal exploratory behavior. This demonstrates relationships between glucocorticoids, fluoxetine, and exploration in this fish.

Fluoxetine has an anti-nematode effect. Choy et al., 1999 finds some of this effect is due to interference with certain transmembrane proteins.

Further reading

- Shorter E (2014). "The 25th anniversary of the launch of Prozac gives pause for thought: where did we go wrong?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 331–2. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.129916. PMID 24785765.

- Haberman C (21 September 2014). "Selling Prozac as the Life-Enhancing Cure for Mental Woes". The New York Times.

External links

- "Fluoxetine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Fluoxetine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT1AR agonists | |

|---|---|

| GABAAR PAMs |

|

|

Gabapentinoids |

|

| Antidepressants |

|

|

Sympatholytics |

|

| Others | |

| |

| Antidepressants | |

|---|---|

| Others | |

|

DAT (DRIs) |

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NET (NRIs) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

SERT (SRIs) |

|

||||||||||||||

| VMATs | |||||||||||||||

| Others |

|

||||||||||||||

| 5-HT1 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT3–7 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| σ1 |

|

|---|---|

| σ2 | |

| Unsorted |

|

See also: Receptor/signaling modulators | |

| Alcohols | |

|---|---|

| Barbiturates |

|

| Benzodiazepines |

|

| Carbamates | |

| Flavonoids |

|

| Imidazoles | |

| Kava constituents | |

| Monoureides | |

| Neuroactive steroids |

|

| Nonbenzodiazepines | |

| Phenols | |

| Piperidinediones | |

| Pyrazolopyridines | |

| Quinazolinones | |

| Volatiles/gases |

|

| Others/unsorted |

|