- Bryophyte

- Fern

- Flowering plant

- Gymnosperm

- Lycophyte

- Plants

- Plant ecology

- Plant reproduction

- Evolution of plants

- Historically recognized plant taxa

- Monotypic plant taxa

- Plants and humans

- Plants by morphology

- Plants by year of formal description

- Plants that can bloom all year round

- Plant families

- Plant genera

- Plant orders

- Plant redirects

- Plant subfamilies

- Plant taxa by rank

- Prehistoric plants

- Set index articles on plants

Plants

| Plants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| (unranked): | Archaeplastida |

| Kingdom: |

Plantae sensu Copeland, 1956 |

| Superdivisions | |

|

see text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes, forming the kingdom Plantae. Many are multicellular. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi. All current definitions exclude the fungi and some of the algae. By one definition, plants form the clade Viridiplantae (Latin for "green plants") which consists of the green algae and the embryophytes or land plants. The latter include hornworts, liverworts, mosses, lycophytes, ferns, conifers and other gymnosperms, and flowering plants. A definition based on genomes includes the Viridiplantae, along with the red algae and the glaucophytes, in the clade Archaeplastida.

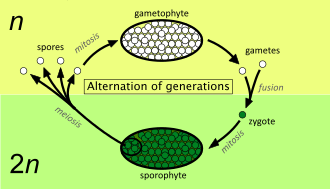

Green plants obtain most of their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria. Chloroplasts perform photosynthesis using the pigment chlorophyll, which gives them their green colour. Some plants are parasitic and have lost the ability to produce normal amounts of chlorophyll or to photosynthesize. Plants are characterized by sexual reproduction and alternation of generations, but asexual reproduction is also common.

There are about 380,000 known species of plants, of which the majority, some 260,000, produce seeds. Green plants provide a substantial proportion of the world's molecular oxygen and are the basis of most of Earth's ecosystems. Grain, fruit, and vegetables are basic human foods and have been domesticated for millennia. Plants have many cultural and other uses, such as ornaments, building materials, writing materials, and, in great variety, they have been the source of medicines. The scientific study of plants is known as botany, a branch of biology.

Definition

Taxonomic history

All living things were traditionally placed into one of two groups, plants and animals. This classification dates from Aristotle (384–322 BC), who distinguished different levels of beings in his biology, based on whether living things have locomotion or had sensory organs.Theophrastus, Aristotle's student, continued his work in plant taxonomy and classification. Much later, Linnaeus (1707–1778) created the basis of the modern system of scientific classification, but retained the animal and plant kingdoms.

Alternative concepts

When the name Plantae or plant is applied to a specific group of organisms or taxon, it usually refers to one of four concepts. From least to most inclusive, these four groupings are:

| Name(s) | Scope | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Land plants, also known as Embryophyta | Plantae sensu strictissimo | Plants in the strictest sense include liverworts, hornworts, mosses, and vascular plants, as well as fossil plants similar to these surviving groups (e.g., Metaphyta Whittaker, 1969, Plantae Margulis, 1971). |

| Green plants, also known as Viridiplantae, Viridiphyta, Chlorobionta or Chloroplastida | Plantae sensu stricto | Plants in a strict sense include the green algae, and land plants that emerged within them, including stoneworts. The relationships between plant groups are still being worked out, and the names given to them vary considerably. The clade Viridiplantae encompasses a group of organisms that have cellulose in their cell walls, possess chlorophylls a and b and have plastids bound by only two membranes that are capable of photosynthesis and of storing starch. This clade is the main subject of this article (e.g., Plantae Copeland, 1956). |

| Archaeplastida, also known as Plastida or Primoplantae | Plantae sensu lato | Plants in a broad sense comprise the green plants listed above plus the red algae (Rhodophyta) and the glaucophyte algae (Glaucophyta) that store Floridean starch outside the plastids, in the cytoplasm. This clade includes all of the organisms that eons ago acquired their primary chloroplasts directly by engulfing cyanobacteria (e.g., Plantae Cavalier-Smith, 1981). |

| Old definitions of plant (obsolete) | Plantae sensu amplo | Plants in the widest sense refers to older, obsolete classifications that placed the unrelated groups of algae, fungi and bacteria in Plantae (e.g., Plantae or Vegetabilia Linnaeus, Plantae Haeckel 1866, Metaphyta Haeckel, 1894, Plantae Whittaker, 1969). |

Evolution

Diversity

There are about 382,000 accepted species of plants, of which the great majority, some 293,000, produce seeds. The table below shows some species count estimates of different green plant (Viridiplantae) divisions. About 85–90% of all plants are flowering plants. Several projects are currently attempting to collect records on all plant species in online databases, e.g. the World Flora Online.

Plants range in scale from single cells, such as many algae including desmids (from 10 micrometres across) and picozoans (less than 3 micrometres across), to trees such as the conifer Sequoia sempervirens (up to 380 feet (120 m) tall ) and the angiosperm Eucalyptus regnans (up to 325 feet (99 m) tall ).

| Informal group | Division name | Common name | No. of living species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green algae | Chlorophyta | Green algae (chlorophytes) | 3800–4300 |

| Charophyta | Green algae (e.g. desmids & stoneworts) | 2800–6000 | |

| Bryophytes | Marchantiophyta | Liverworts | 6000–8000 |

| Anthocerotophyta | Hornworts | 100–200 | |

| Bryophyta | Mosses | 12000 | |

| Pteridophytes | Lycopodiophyta | Clubmosses | 1200 |

| Polypodiophyta | Ferns, whisk ferns & horsetails | 11000 | |

|

Spermatophyte (seed plants) |

Cycadophyta | Cycads | 160 |

| Ginkgophyta | Ginkgo | 1 | |

| Pinophyta | Conifers | 630 | |

| Gnetophyta | Gnetophytes | 70 | |

| Magnoliophyta | Flowering plants | 258650 |

The naming of plants is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants and the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants.

Evolutionary scenarios

The ancestors of land plants evolved in water. An algal scum formed on the land 1,200 million years ago, but it was not until the Ordovician, around 450 million years ago, that the first land plants appeared, with a level of organisation like that of bryophytes. However, evidence from carbon isotope ratios in Precambrian rocks suggests that complex plants developed over 1000 mya.

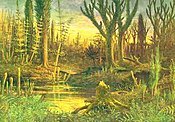

Primitive land plants began to diversify in the late Silurian, around 420 million years ago. Bryophytes, club mosses, ferns then appear in the fossil record. Early plant anatomy is preserved in cellular detail in an early Devonian fossil assemblage from the Rhynie chert. These early plants were preserved by being petrified in chert formed in silica-rich volcanic hot springs.

By the end of the Devonian, most of the basic features of plants today were present, including roots, leaves and secondary wood in trees such as Archaeopteris. The Carboniferous Period saw the development of forests in swampy environments dominated by clubmosses and horsetails, including some as large as trees, and the appearance of early gymnosperms, the first seed plants. The Permo-Triassic extinction event radically changed the structures of communities. This may have set the scene for the evolution of flowering plants in the Triassic (~200 million years ago), with an adaptive radiation in the Cretaceous so rapid that Darwin called it an "abominable mystery".Conifers diversified from the Late Triassic onwards, and became a dominant part of floras in the Jurassic.

Cross-section of a stem of Rhynia, an early land plant, preserved in Rhynie chert from the early Devonian

By the Devonian, plants had adapted to land with roots and woody stems.

In the Carboniferous, horsetails such as Asterophyllites proliferated in swampy forests.

Conifers became diverse and often dominant in the Jurassic. Cone of Araucaria mirabilis.

Adaptive radiation in the Cretaceous created many flowering plants, such as Sagaria in the Ranunculaceae.

Towards a phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree of Plantae, proposed in 1997 by Kenrick and Crane, is as follows. The Prasinophyceae are a paraphyletic assemblage of early diverging green algal lineages, but are treated as a group outside the Chlorophyta:

| Plantae |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, some of them (the Prasinodermophyta) appear be a basal plant group.

A different classification followed Leliaert et al. 2011 and modified with Silar 2016 for the green algae clades and Novíkov & Barabaš-Krasni 2015 for the land plants clade. Notice that the Prasinophyceae are here placed inside the Chlorophyta.

|

Genomic phylogeny

In 2019, a phylogeny based on genomes and transcriptomes from 1,153 plant species was proposed. The placing of algal groups is supported by phylogenies based on genomes from the Mesostigmatophyceae and Chlorokybophyceae that have since been sequenced. Both the "chlorophyte algae" and the "streptophyte algae" are treated as paraphyletic (vertical bars beside phylogenetic tree diagram) in this analysis, as the land plants arose from within those groups. The classification of Bryophyta is supported both by Puttick et al. 2018, and by phylogenies involving the hornwort genomes that have also since been sequenced.

| Archaeplastida |

|

"chlorophyte algae"

"streptophyte algae"

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physiology

Plant cells

Plant cells have some distinctive features that other eukaryotic cells (such as those of animals) lack. These are the large water-filled central vacuole, chloroplasts, and the strong flexible cell wall, which is outside the cell membrane. Chloroplasts are derived from what was once a symbiosis of a non-photosynthetic cell and photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The cell wall, made mostly of cellulose, allows plant cells to swell up with water without bursting. The vacuole allows the cell to change in size while the amount of cytoplasm stays the same.

Plant structure

Most plants are multicellular. Just as in animals, plant cells differentiate and develop into multiple cell types, forming tissues such as the vascular tissue with specialized xylem and phloem of leaf veins and stems, and organs with different physiological functions such as roots to absorb water and minerals, stems for support and to transport water and synthesised molecules, leaves for photosynthesis, and flowers for reproduction.

Photosynthesis

Plants photosynthesize, manufacturing food molecules using energy obtained from light. The primary mechanism plants have for capturing light energy is the green pigment chlorophyll, which plant cells have in their chloroplasts. The simple equation of photosynthesis is:

This means that they release oxygen into the atmosphere. Green plants provide a substantial proportion of the world's molecular oxygen, alongside the contributions from photosynthetic algae and cyanobacteria.

Growth and repair

Growth is determined by the interaction of a plant's genome with its physical and biotic environment. Factors of the physical or abiotic environment include temperature, water, light, carbon dioxide, and nutrients in the soil. Biotic factors that affect plant growth include crowding, grazing, beneficial symbiotic bacteria and fungi, and attacks by insects or plant diseases.

Frost and dehydration can damage or kill plants. Some plants have antifreeze proteins, heat-shock proteins and sugars in their cytoplasm that enable them to tolerate these stresses. Plants are continuously exposed to a range of physical and biotic stresses which cause DNA damage. Plants are able to tolerate and repair much of this damage.

Reproduction

Plants reproduce to generate offspring, whether sexually, involving gametes, or asexually, involving ordinary growth. Many plants use both mechanisms.

Sexual

When reproducing sexually, plants have complex lifecycles involving alternation of generations. One generation, the sporophyte, which is diploid (with 2 sets of chromosomes), gives rise to the next generation, the gametophyte which is haploid (with one set of chromosomes), and in some plants reproduces asexually via spores. In non-flowering plants such as mosses and ferns, the sexual gametophyte forms most of the visible plant. In seed plants (gymnosperms and flowering plants), the sporophyte forms most of the visible plant, and the gametophyte is very small. Flowering plants reproduce sexually using flowers, which contain male and female parts: these may be within the same (hermaphrodite) flower, on different flowers on the same plant, or on different plants. Male pollen enters the ovule to fertilize the egg cell of the female gametophyte. Fertilization takes place enclosed within the carpels or ovaries, which develop into fruits that contain seeds. Fruits may be dispersed whole, or they may split open and the seeds dispersed individually.

Asexual

Plants reproduce asexually by growing any of a wide variety of structures capable of growing into new plants. At the simplest, plants such as mosses or liverworts may be broken into pieces, each of which may regrow into whole plants. The propagation of flowering plants by cuttings is a similar process. Structures such as runners enable plants to grow to cover an area, forming a clone. Many plants grow food storage structures such as tubers or bulbs which may each develop into a new plant.

Some non-flowering plants, such as many liverworts, mosses and some clubmosses, along with a few flowering plants, grow small clumps of cells called gemmae which can detach and grow.

Disease resistance

Plants use pattern-recognition receptors to recognize pathogens such as bacteria that cause plant diseases. This recognition triggers a protective response. The first such plant receptors were identified in rice and in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Genomics

Plants have some of the largest genomes among all organisms. The largest plant genome (in terms of gene number) is that of wheat (Triticum aestivum), predicted to encode ≈94,000 genes and thus almost 5 times as many as the human genome. The first plant genome sequenced was that of Arabidopsis thaliana which encodes about 25,500 genes. In terms of sheer DNA sequence, the smallest published genome is that of the carnivorous bladderwort (Utricularia gibba) at 82 Mb (although it still encodes 28,500 genes) while the largest, from the Norway Spruce (Picea abies), extends over 19.6 Gb (encoding about 28,300 genes).

Ecology

Distribution

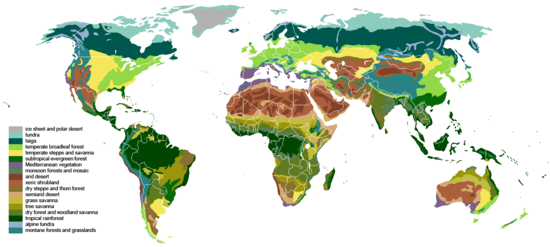

Plants are distributed almost worldwide. While they inhabit several biomes which can be divided into a multitude of ecoregions, only the hardy plants of the Antarctic flora, consisting of algae, mosses, liverworts, lichens, and just two flowering plants, have adapted to the prevailing conditions on that southern continent.

Plants are often the dominant physical and structural component of the habitats where they occur. Many of the Earth's biomes are named for the type of vegetation because plants are the dominant organisms in those biomes, such as grassland, savanna, and tropical rainforest.

Primary producers

The photosynthesis conducted by land plants and algae is the ultimate source of energy and organic material in nearly all ecosystems. Photosynthesis, at first by cyanobacteria and later by photosynthetic eukaryotes, radically changed the composition of the early Earth's anoxic atmosphere, which as a result is now 21% oxygen. Animals and most other organisms are aerobic, relying on oxygen; those that do not are confined to relatively rare anaerobic environments. Plants are the primary producers in most terrestrial ecosystems and form the basis of the food web in those ecosystems. Plants form about 80% of the world biomass at about 450 gigatonnes (4.4×1011 long tons; 5.0×1011 short tons) of carbon.

Ecological relationships

Numerous animals have coevolved with plants; flowering plants have evolved pollination syndromes, suites of flower traits that favour their reproduction. Many, including insect and bird partners, are pollinators, visiting flowers and accidentally transferring pollen in exchange for food in the form of pollen or nectar.

Many animals disperse seeds that are adapted for such dispersal. Various mechanisms of dispersal have evolved. Some fruits offer nutritious outer layers attractive to animals, while the seeds are adapted to survive the passage through the animal's gut; others have hooks that enable them to attach to a mammal's fur.Myrmecophytes are plants that have coevolved with ants. The plant provides a home, and sometimes food, for the ants. In exchange, the ants defend the plant from herbivores and sometimes competing plants. Ant wastes serve as organic fertilizer.

The majority of plant species have fungi associated with their root systems in a mutualistic symbiosis known as mycorrhiza. The fungi help the plants gain water and mineral nutrients from the soil, while the plant gives the fungi carbohydrates manufactured in photosynthesis. Some plants serve as homes for endophytic fungi that protect the plant from herbivores by producing toxins. The fungal endophyte Neotyphodium coenophialum in tall fescue grass has pest status in the American cattle industry.

Many legumes have Rhizobium nitrogen-fixing bacteria in nodules of their roots, which fix nitrogen from the air for the plant to use; in return, the plants supply sugars to the bacteria. Nitrogen fixed in this way can become available to other plants, and is important in agriculture; for example, farmers may grow a crop rotation of a legume such as beans, followed by a cereal such as wheat, to provide cash crops with a reduced input of nitrogen fertilizer.

Some 1% of plants are parasitic. They range from the semi-parasitic mistletoe that merely takes some nutrients from its host, but still has photosynthetic leaves, to the fully-parasitic broomrape and toothwort that acquire all their nutrients through connections to the roots of other plants, and so have no chlorophyll. Full parasites can be extremely harmful to their plant hosts.

Plants that grow on other plants, usually trees, without parasitizing them, are called epiphytes. These may support diverse arboreal ecosystems. Some may indirectly harm their host plant, such as by intercepting light. Hemiepiphytes like the strangler fig begin as epiphytes, but eventually set their own roots and overpower and kill their host. Many orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and mosses grow as epiphytes. Among the epiphytes, the bromeliads accumulate water in their leaf axils; these water-filled cavities can support complex aquatic food webs.

Some 630 species of plants are carnivorous, such as the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) and sundew (Drosera species). They trap small animals and digest them to obtain mineral nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus.

Bee gathering pollen (orange pollen basket on its leg)

Hummingbird visiting a flower for nectar

Seed dispersal by animals: many hooked Geum urbanum fruits attached to a dog's fur

Legumes have root nodules containing symbiotic Rhizobium nitrogen fixing bacteria.

A sundew leaf with sticky hairs curling to trap and digest a fly

Competition

Competition for shared resources reduces a plant's growth. Shared resources include sunlight, water and nutrients. Light is a critical resource because it is necessary for photosynthesis. Plants use their leaves to shade other plants from sunlight and grow quickly to maximize their own expose. Water too is essential for photosynthesis; roots compete to maximize water uptake from soil. Some plants have deep roots that are able to locate water stored deep underground, and others have shallower roots that are capable of extending longer distances to collect recent rainwater. Minerals are important for plant growth and development. Common nutrients competed for amongst plants include nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Importance

Food

Human cultivation of plants is the core of agriculture, which in turn has played a key role in the history of world civilizations. Humans depend on plants for food, either directly or as feed in animal husbandry. Agriculture includes agronomy for arable crops, horticulture for vegetables and fruit, and forestry for timber. About 7,000 species of plant have been used for food, though most of today's food is derived from only 30 species. The major staples include cereals such as rice and wheat, starchy roots and tubers such as cassava and potato, and legumes such as peas and beans. Vegetable oils such as olive oil and palm oil provide lipids, while fruit and vegetables contribute vitamins and minerals to the diet. The study of plant uses by people is called economic botany or ethnobotany.

Medicines

Medicinal plants are a primary source of organic compounds, both for their medicinal and physiological effects, and for the industrial synthesis of a vast array of organic chemicals. Many hundreds of medicines are derived from plants, both traditional medicines used in herbalism and chemical substances purified from plants or first identified in them, sometimes by ethnobotanical search, and then synthesised for use in modern medicine. Modern medicines derived from plants include aspirin, taxol, morphine, quinine, reserpine, colchicine, digitalis and vincristine. Plants used in herbalism include ginkgo, echinacea, feverfew, and Saint John's wort. The pharmacopoeia of Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, describing some 600 medicinal plants, was written between 50 and 70 CE and remained in use in Europe and the Middle East until around 1600 CE; it was the precursor of all modern pharmacopoeias.

Nonfood products

Plants grown as industrial crops are the source of a wide range of products used in manufacturing. Nonfood products include essential oils, natural dyes, pigments, waxes, resins, tannins, alkaloids, amber and cork. Products derived from plants include soaps, shampoos, perfumes, cosmetics, paint, varnish, turpentine, rubber, latex, lubricants, linoleum, plastics, inks, and gums. Renewable fuels from plants include firewood, peat and other biofuels. The fossil fuels coal, petroleum and natural gas are derived from the remains of aquatic organisms including phytoplankton in geological time. Many of the coal fields date to the Carboniferous period of Earth's history. Terrestrial plants also form type III kerogen, a source of natural gas.

Structural resources and fibres from plants are used to construct dwellings and to manufacture clothing. Wood is used for buildings, boats, and furniture, and for smaller items such as musical instruments and sports equipment. Wood is pulped to make paper and cardboard. Cloth is often made from cotton, flax, ramie or synthetic fibres such as rayon and acetate derived from plant cellulose. Thread used to sew cloth likewise comes in large part from cotton.

Ornamental plants

Thousands of plant species are cultivated for their beauty and to provide shade, modify temperatures, reduce wind, abate noise, provide privacy, and reduce soil erosion. Plants are the basis of a multibillion-dollar per year tourism industry, which includes travel to historic gardens, national parks, rainforests, forests with colorful autumn leaves, and festivals such as Japan's and America's cherry blossom festivals.

Plants may be grown indoors as houseplants, or in specialized buildings such as greenhouses. Plants such as Venus flytrap, sensitive plant and resurrection plant are sold as novelties. Art forms specializing in the arrangement of cut or living plant include bonsai, ikebana, and the arrangement of cut or dried flowers. Ornamental plants have sometimes changed the course of history, as in tulipomania.

In science

Basic biological research has often used plants as its model organisms. In genetics, the breeding of pea plants allowed Gregor Mendel to derive the basic laws governing inheritance, and examination of chromosomes in maize allowed Barbara McClintock to demonstrate their connection to inherited traits. The plant Arabidopsis thaliana is used in laboratories as a model organism to understand how genes control the growth and development of plant structures.Tree rings provide a method of dating in archeology, and a record of past climates. The study of plant fossils, or Paleobotany, provides information about the evolutions of plants, paleogeographical reconstructions, and past climate change. Plant fossils can also help determine the age of rocks.

In mythology, religion, and culture

Plants including trees appear in mythology, religion, and literature. Flowers are often used as memorials, gifts and to mark special occasions such as births, deaths, weddings and holidays. Flower arrangements may be used to send hidden messages. Architectural designs resembling plants appear in the capitals of Ancient Egyptian columns, which were carved to resemble either the Egyptian white lotus or the papyrus. Images of plants and especially of flowers are often used in paintings.

Negative effects

Weeds are commercially or aesthetically undesirable plants growing in managed environments such as in agriculture and gardens. People have spread many plants beyond their native ranges; some of these plants have become invasive, damaging existing ecosystems by displacing native species, and sometimes becoming serious weeds of cultivation.

Some plants that produce windblown pollen, including grasses, invoke allergic reactions in people who suffer from hay fever. Many plants produce toxins to protect themselves from herbivores. Major classes of plant toxins include alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics. These can be harmful to humans and livestock by ingestion or, as with poison ivy, by contact. Some plants have negative effects on other plants, preventing seedling growth or the growth of nearby plants by releasing allopathic chemicals.

See also

Further reading

General:

- Evans, L.T. (1998). Feeding the Ten Billion – Plants and Population Growth. Cambridge University Press. Paperback, 247 pages. ISBN 0-521-64685-5.

- Kenrick, Paul & Crane, Peter R. (1997). The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-730-8.

- Raven, Peter H.; Evert, Ray F.; & Eichhorn, Susan E. (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

- Taylor, Thomas N. & Taylor, Edith L. (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-651589-4.

Species estimates and counts:

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (2004). IUCN Red List The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Prance, G. T. (2001). "Discovering the Plant World". Taxon. 50 (2, Golden Jubilee Part 4): 345–359. doi:10.2307/1223885. JSTOR 1223885.

External links

- Index Nominum Algarum

- Interactive Cronquist classification

- Plant Resources of Tropical Africa

- Tree of Life Archived 9 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Botanical and vegetation databases

- African Plants Initiative database

- Australia

- Chilean plants at Chilebosque

- e-Floras (Flora of China, Flora of North America and others) Archived 19 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Flora Europaea

- Flora of Central Europe (in German)

- Flora of North America Archived 19 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- List of Japanese Wild Plants Online Archived 16 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Meet the Plants-National Tropical Botanical Garden

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Native Plant Information Network at University of Texas, Austin

- United States Department of Agriculture not limited to continental US species

| Subdisciplines | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant groups | |||||||||||

| Plant anatomy |

|

||||||||||

|

Plant physiology Materials |

|||||||||||

| Plant growth and habit |

|||||||||||

| Reproduction | |||||||||||

| Plant taxonomy | |||||||||||

| Practice | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Classification of Archaeplastida or Plantae

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gardening | |

|---|---|

| Types of gardens |

|

| Horticulture | |

| Organic | |

| Plant protection | |

| Related articles | |

|

Extant life phyla/divisions by domain

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Life, non-cellular life, and comparable structures

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular life |

|

||||||||||||||

| Non-cellular life |

|

||||||||||||||

| Comparable structures |

|

||||||||||||||

| Taxon identifiers |

|

|---|

| National | |

|---|---|

| Other | |

![{\displaystyle {\ce {6CO2{}+6H2O{}->[{\text{light}}]C6H12O6{}+6O2{}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/100302228047a00799cc68db892940dd5e3adc9e)