Rhinovirus

| Rhinovirus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rhinovirus | |

|

Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Picornaviridae |

| Genus: | Enterovirus |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

| |

The rhinovirus (from the Ancient Greek: ῥίς, romanized: rhis "nose", gen ῥινός, romanized: rhinos "of the nose", and the Latin: vīrus) is the most common viral infectious agent in humans and is the predominant cause of the common cold. Rhinovirus infection proliferates in temperatures of 33–35 °C (91–95 °F), the temperatures found in the nose. Rhinoviruses belong to the genus Enterovirus in the family Picornaviridae.

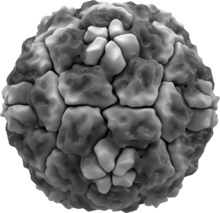

The three species of rhinovirus (A, B, and C) include around 165 recognized types that differ according to their surface antigens or genetics. They are lytic in nature and are among the smallest viruses, with diameters of about 30 nanometers. By comparison, other viruses, such as smallpox and vaccinia, are around ten times larger at about 300 nanometers, while flu viruses are around 80–120 nm.

History

In 1953, when a cluster of nurses developed a mild respiratory illness, Winston Price, from the Johns Hopkins University, took nasal passage samples and isolated the first rhinovirus, which he called the JH virus, named after Johns Hopkins. His findings were published in 1956.

Transmission and epidemiology

Rhinoviruses may be spread via airborne aerosols, respiratory droplets and from fomites (contaminated surfaces), including direct person-to-person contact.

Rhinoviruses are spread worldwide and are the primary cause of the common cold. Symptoms include sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, sneezing and cough; sometimes accompanied by muscle aches, fatigue, malaise, headache, muscle weakness, or loss of appetite. Most sinus findings are reversible consistent with a self-limited viral process typical of rhinovirus colds. Fever and extreme exhaustion are more usual in influenza. Children may have six to twelve colds a year. In the United States, the incidence of colds is higher in the autumn and winter, with most infections occurring between September and April. The seasonality may be due to the start of the school year and to people spending more time indoors thereby increasing the chance of transmission of the virus. Lower ambient temperatures, especially outdoors, may also be a factor given that rhinoviruses preferentially replicate at 32 °C (89 °F) as opposed to 37 °C (98 °F). Variant pollens, grasses, hays and agricultural practices may be factors in the seasonality as well as the use of chemical controls of lawn, paddock and sportsfields in schools and communities. The changes in temperature, humidity and wind patterns seem to be factors.

Those most affected by rhinoviruses are infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised people.

Pathogenesis

The primary route of entry for human rhinoviruses is the upper respiratory tract (mouth and nose). Rhinovirus A and B use "major" ICAM-1 (Inter-Cellular Adhesion Molecule 1), also known as CD54 (Cluster of Differentiation 54), on respiratory epithelial cells, as receptors to bind to. Some subgroups under A and B uses the "minor" LDL receptor instead. Rhinovirus C uses cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3) to mediate cellular entry. As the virus replicates and spreads, infected cells release distress signals known as chemokines and cytokines (which in turn activate inflammatory mediators). Cell lysis occurs at the upper respiratory epithelium.

Infection occurs rapidly, with the virus adhering to surface receptors within 15 minutes of entering the respiratory tract. Just over 50% of individuals will experience symptoms within 2 days of infection. Only about 5% of cases will have an incubation period of less than 20 hours, and, at the other extreme, it is expected that 5% of cases would have an incubation period of greater than four and a half days.

Human rhinoviruses preferentially grow at 32 °C (89 °F), notably colder than the average human body temperature of 37 °C (98 °F); hence the virus's tendency to infect the upper respiratory tract, where respiratory airflow is in continual contact with the (colder) extrasomatic environment.

Rhinovirus C, unlike the A and B species, may be able to cause severe infections. This association disappears after controlling for confounders. Duly, amongst infants infected with symptomatic respiratory illness in low-resource areas, there appears to be no association between rhinovirus species and disease severity.

Taxonomy

Rhinovirus was formerly classified as a genus of the family Picornaviridae. The 39th Executive Committee (EC39) of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) met in Canada during June 2007 with new taxonomic proposals. In April 2008, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses voted and ratified the following changes:

- 2005.264V.04 To remove the following species from the existing genus Rhinovirus in the family Picornaviridae:

- Human rhinovirus A

- Human rhinovirus B

- 2005.265V.04 To assign the following species to the genus Enterovirus in the family Picornaviridae:

- Human rhinovirus A

- Human rhinovirus B

- 2005.266V.04 To remove the existing genus Rhinovirus from the family Picornaviridae. Note: The genus Rhinovirus hereby disappears.

The merge is based on the grounds that the two "genera" of viruses are not significantly different in a virological sense. They have identical genome organizations and particle structures, and the phylogeny is not always monophyletic.

In July 2009, the ICTV voted and ratified a proposal to add a third species, Human rhinovirus C to the genus Enterovirus.

- 2008.084V.A.HRV-C-Sp 2008.084V To create a new species named Human rhinovirus C in the genus Enterovirus, family Picornaviridae.

There have been a total of 215 taxonomic proposals, which have been approved and ratified since the 8th ICTV Report of 2005.

Types

Prior to 2020, enteroviruses (including all rhinoviruses) were categorized according to their serotype. In 2020 the ICTV ratified a proposal to classify all new types based on the genetic diversity of their VP1 gene. Human rhinovirus type names are of the form RV-Xn where X is the rhinovirus species (A, B, or C) and n is an index number. Species A and B have used the same index up to number 100, while species C has always used a separate index. Valid index numbers are as follows:

- Rhinovirus A: 1, 1B, 2, 7–13, 15, 16, 18–25, 28–34, 36, 38–41, 43–47, 49–51, 53–68, 71, 73–78, 80–82, 85, 88–90, 94–96, 100–108

- Rhinovirus B: 3–6, 14, 17, 26, 27, 35, 37, 42, 48, 52, 69, 70, 72, 79, 83, 84, 86, 91–93, 97, 99, 100-104

- Rhinovirus C: 1–57

Structure

Rhinoviruses have single-stranded positive sense RNA genomes of between 7200 and 8500 nt in length. At the 5' end of the genome is a virus-encoded protein and, as in mammalian mRNA, there is a 3' poly-A tail. Structural proteins are encoded in the 5' region of the genome and non structural at the 3' end. This is the same for all picornaviruses. The viral particles themselves are not enveloped and are dodecahedral in structure.

The viral proteins are translated as a single long polypeptide, which is cleaved into the structural and nonstructural viral proteins.

Human rhinoviruses are composed of a capsid that contains four viral proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4. VP1, VP2, and VP3 form the major part of the protein capsid. The much smaller VP4 protein has a more extended structure, and lies at the interface between the capsid and the RNA genome. There are 60 copies of each of these proteins assembled as an icosahedron. Antibodies are a major defense against infection with the epitopes lying on the exterior regions of VP1-VP3.

Novel antiviral drugs

Interferon-alpha used intranasally was shown to be effective against human rhinovirus infections. However, volunteers treated with this drug experienced some side effects, such as nasal bleeding, and began developing tolerance to the drug. Subsequently, research into the treatment was abandoned.

Pleconaril is an orally bioavailable antiviral drug being developed for the treatment of infections caused by picornaviruses. This drug acts by binding to a hydrophobic pocket in VP1, and stabilizes the protein capsid to such an extent that the virus cannot release its RNA genome into the target cell. When tested in volunteers, during the clinical trials, this drug caused a significant decrease in mucus secretions and illness-associated symptoms. Pleconaril is not currently available for treatment of human rhinoviral infections, as its efficacy in treating these infections is under further evaluation.

Other substances such as Iota-Carrageenan may form a basis for the creation of drugs to combat the human rhinovirus.

In asthma, human rhinoviruses have been recently associated with the majority of asthma exacerbations for which current therapy is inadequate. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) has a central role in airway inflammation in asthma, and it is the receptor for 90% of Human rhinoviruses. Human rhinovirus infection of airway epithelium induces ICAM-1.

Desloratadine and loratadine are compounds belonging to the new class of H1-receptor blockers. Anti-inflammatory properties of antihistamines have been recently documented, although the underlying molecular mechanisms are not completely defined. These effects are unlikely to be mediated by H1-receptor antagonism and suggest a novel mechanism of action that may be important for the therapeutic control of virus-induced asthma exacerbations.

In 2018, a new series of anti-rhinoviral compounds were reported by researchers at Imperial College London and colleagues at the University of York and the Pirbright Institute. These molecules target human N-myristoyltransferase, an enzyme in the host cell which picornavirus requires in order to assemble its viral capsid, and thus generate an infectious virion. The lead compound in this series, IMP-1088, very potently inhibited host myristoylation of viral capsid protein and prevented infectious virus formation, rescuing the viability of cells in culture which had been exposed to a variety of rhinovirus serotypes, or to related picornaviruses including poliovirus and foot-and-mouth-disease virus. Because these compounds target a host factor, they are broadly active against all serotypes, and it is thought to be unlikely that they can be overcome by resistance mutations in the virus.

Vaccine

There are no vaccines against these viruses as there is little-to-no cross-protection between serotypes. At least 99 serotypes of human rhinoviruses affecting humans have been sequenced. However, a study of the VP4 protein has shown it to be highly conserved among many serotypes of human rhinovirus, opening up the potential for a future pan-serotype human rhinovirus vaccine. A similar result was obtained with the VP1 protein. Like VP4, VP1 also occasionally "pokes" out of the viral particle, making it available to neutralizing antibodies. Both peptides have been tested on rabbits, resulting in successful generation of cross-serotype antibodies.

The successful introduction of human ICAM-1 into mice has removed a major roadblock in creating an animal model for RV vaccination.

Prevention of Rhinovirus is very challenging as there are no official or approved vaccines or preventative measures for Rhinovirus. The lack of data and knowledge of Rhinovirus poses obstacles to the development of a vaccine. Better understanding and study have been promoted in recent years in order to provide treatment and prevention for one of the most common human viruses. These challenges include over 100 unique Rhinovirus serotypes with recent discoveries of even more, a lack of data indicating the most common strains of HRV in the human population, and a lack of understanding of the antigenic differences between Rhinovirus serotypes along with limited studies including animal models of HRV infection and pathogenesis. Rhinovirus research has typically been neglected as it occurs most synonymously as the common cold. Recent attention to the effects of viruses on the immunocompromised have brought more attention to researching this very common infection. Currently, the treatment for Rhinovirus is typically only for those in palliative care as a large portion of the population is able to recover from a Rhinovirus infection.

However, Rhinovirus can pose a life-threatening risk to those that have immunocompromising conditions, such as those with asthma who appear to be at greater risk of severe infections from Rhinovirus, as it poses to exacerbate symptoms of asthma. Treatments for those with asthma have been progressed as IFN-, a cytokine modulator shown to attenuate stronger symptoms of asthma onset by a Rhinovirus infection. Despite the increasing risk it poses to those with preexisting conditions, Rhinovirus has itself demonstrated an ability to act similar to an attenuated virus for stronger respiratory infection caused by other viruses. It has the ability, in milder infections, to promote antiviral immunity in the upper respiratory tract against other viruses such as Influenza and SARS-CoV-2. Rhinovirus has a mutation rate similar to that of Influenza which, along with SARS-COV2, has a vaccine treatment. Rate of mutation is not what poses an issue to Rhinovirus vaccination. Rhinovirus genome has a high rate of variability in human circulation, even occurring with genomic sequences that differ up to 30%. Recent studies have identified conserved regions of the Rhinovirus genome; this, along with an adjuvanted polyvalent Rhinovirus vaccine, shows potential for future development in vaccine treatment.

Prevention

Human rhinovirus can remain activated for up to three hours outside of a human host. Once the virus is contracted, a person is most contagious within the first three days. Preventative measures such as regular vigorous handwashing with soap and water may aid in avoiding infection. Avoiding touching the mouth, eyes, and nose (the most common entry points for rhinovirus) may also assist prevention. Droplet precautions, which take the form of a surgical mask and gloves, are the method used in major hospitals.

External links

- VIDEO: Rhinoviruses, the Old, the New and the UW James E. Gern, MD, speaks at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 2008.

- How Big is a Human rhinovirus? (animation)

| Viruses | |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Complications | |

| Drugs |

|