Fentanyl

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛntənɪl/ or /ˈfɛntənəl/ |

| Trade names | Actiq, Duragesic, Sublimaze, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605043 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability |

High |

| Routes of administration |

Buccal, epidural, intramuscular, intrathecal, intravenous, sublingual, transdermal |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92% (transdermal) 65% (intranasal) 50% (buccal) 33% (ingestion) 100% (intramuscular) 80% (inhaled) 100% (intravenous) |

| Protein binding | 80–85% |

| Metabolism | Liver, primarily by CYP3A4 |

| Onset of action | 5 minutes |

| Elimination half-life |

IV: 6 mins (T1/2 α) 1 hours (T1/2 β) 16 hours (T1/2 ɣ) Intranasal: 15-25 hours Transdermal: 20–27 hours Sublingual (single dose): 5–13.5 hours Buccal: 3.2-6.4 hours |

| Duration of action | IV: 30–60 minutes |

| Excretion | Mostly urinary (metabolites, < 10% unchanged drug) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.468 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

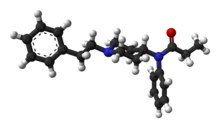

| Formula | C22H28N2O |

| Molar mass | 336.479 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.1 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 87.5 °C (189.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Fentanyl, also spelled fentanil, is a highly potent synthetic piperidine opioid drug primarily used as an analgesic. Because fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, its primary clinical utility is in pain management for cancer patients and those recovering from painful surgical operations. Fentanyl is also used as a sedative. Depending on the method of delivery, fentanyl can be very fast acting and ingesting a relatively small quantity can cause overdose. Fentanyl works by activating mu-opioid receptors. Fentanyl is also commonly known as fentanyl citrate, and is sold under the brand name Sublimaze among others.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl's adverse effects resemble those of other narcotic opioids, including addiction, confusion, respiratory depression (which, if extensive and untreated, may lead to arrest), drowsiness, nausea, visual disturbances, dyskinesia, hallucinations, delirium, a subset of the latter known as "narcotic delirium," analgesia, narcotic ileus, muscle rigidity, constipation, loss of consciousness, hypotension, coma, and death. Alcohol and other drugs (i.e., cocaine, heroin) can synergistically exacerbate fentanyl's side effects. Naloxone (also known as Narcan) can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose; however, because fentanyl is so potent, multiple doses might be necessary.

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Paul Janssen in 1959 and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1968. In 2015, 1,600 kilograms (3,500 pounds) were used in healthcare globally. As of 2017, fentanyl was the most widely used synthetic opioid in medicine; in 2019, it was the 278th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than a million prescriptions. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.

Fentanyl continues to fuel an epidemic of synthetic opioid drug overdose deaths in the United States. While prescription opioid deaths remained stable from 2011 to 2021, synthetic opioid deaths increased from 2,600 overdose deaths per year to 76,238 per year. Since 2018, fentanyl and its analogues have been responsible for most drug overdose deaths in the United States, causing over 71,238 deaths in 2021. Fentanyl constitutes the majority of all drug overdose deaths in the United States since it overtook heroin in 2018.The United States National Forensic Laboratory estimates fentanyl reports by federal, state, and local forensic laboratories increased from 4,697 reports in 2014 to 117,045 reports in 2020. Fentanyl is often mixed, cut, or ingested alongside other drugs, including cocaine and heroin. Fentanyl has been reported in pill form, including pills mimicking pharmaceutical drugs such as oxycodone. Mixing with other drugs or disguising as a pharmaceutical makes it difficult to determine the correct treatment in the case of an overdose, resulting in more deaths. Fentanyl's ease of manufacture and high potency makes it easier to produce and smuggle, resulting in fentanyl replacing other abused narcotics and becoming more widely used.

Medical uses

Anesthesia

Intravenous fentanyl is often used for anesthesia and as an analgesic. To induce anesthesia, it is given with a sedative-hypnotic, like propofol or thiopental, and a muscle relaxant. To maintain anesthesia, inhaled anesthetics and additional fentanyl may be used. These are often given in 15–30 minute intervals throughout procedures such as endoscopy and surgeries and in emergency rooms.

For pain relief after surgery, use can decrease the amount of inhalational anesthetic needed for emergence from anesthesia. Balancing this medication and titrating the drug based on expected stimuli and the person's responses can result in stable blood pressure and heart rate throughout a procedure and a faster emergence from anesthesia with minimal pain.

Regional anesthesia

Fentanyl is the most commonly used intrathecal opioid because its lipophilic profile allows a quick onset of action (5–10 min.) and intermediate duration of action (60–120 min.). Spinal administration of hyperbaric bupivacaine with fentanyl may be the optimal combination. The almost immediate onset of fentanyl reduces visceral discomfort and even nausea during the procedure.

Obstetrics

Fentanyl is sometimes given intrathecally as part of spinal anesthesia or epidurally for epidural anaesthesia and analgesia. Because of fentanyl's high lipid solubility, its effects are more localized than morphine, and some clinicians prefer to use morphine to get a wider spread of analgesia. It is widely used in obstetrical anesthesia because of its short time to action peak (about 5 minutes), the rapid termination of its effect after a single dose, and the occurrence of relative cardiovascular stability. In obstetrics, the dose must be closely regulated in order to prevent large amounts of transfer from mother to fetus. At high doses, the drug may act on the fetus to cause postnatal respiratory distress. For this reason, shorter acting agents such as alfentanyl or remifentanil may be more suitable in the context of inducing general anaesthesia.

Pain management

The bioavailability of intranasal fentanyl is about 70–90%, but with some imprecision due to clotted nostrils, pharyngeal swallow, and incorrect administration. For both emergency and palliative use, intranasal fentanyl is available in doses of 50, 100, and 200 µg. In emergency medicine, safe administration of intranasal fentanyl with a low rate of side effects and a promising pain-reducing effect was demonstrated in a prospective observational study in about 900 out-of-hospital patients.

In children, intranasal fentanyl is useful for the treatment of moderate and severe pain and is well tolerated. Furthermore, a 2017 study suggested the efficacy of fentanyl lozenges in children as young as five, weighing as little as 13 kg. Lozenges are more inclined to be used as the child is in control of sufficient dosage, in contrast to buccal tablets.

Chronic pain

It is also used in the management of chronic pain including cancer pain. Often, transdermal patches are used. The patches work by slowly releasing fentanyl through the skin into the bloodstream over 48 to 72 hours, allowing for long-lasting pain management. Dosage is based on the size of the patch, since, in general, the transdermal absorption rate is constant at a constant skin temperature. Each patch should be changed every 72 hours. Rate of absorption is dependent on a number of factors. Body temperature, skin type, amount of body fat, and placement of the patch can have major effects. The different delivery systems used by different makers will also affect individual rates of absorption, and route of administration. Under normal circumstances, the patch will reach its full effect within 12 to 24 hours; thus, fentanyl patches are often prescribed with a fast-acting opioid (such as morphine or oxycodone) to handle breakthrough pain. It is unclear if fentanyl gives long-term pain relief to people with neuropathic pain.

Breakthrough pain

Sublingual fentanyl dissolves quickly and is absorbed through the sublingual mucosa to provide rapid analgesia. Fentanyl is a highly lipophilic compound, which is well absorbed sublingually and generally well tolerated. Such forms are particularly useful for breakthrough cancer pain episodes, which are often rapid in onset, short in duration, and severe in intensity.

Palliative care

In palliative care, transdermal fentanyl patches have a definitive, but limited role for:

- people already stabilized on other opioids who have persistent swallowing problems and cannot tolerate other parenteral routes such as subcutaneous administration.

- people with moderate to severe kidney failure.

- troublesome side effects of oral morphine, hydromorphone, or oxycodone.

When using the transdermal patch, patients must be careful to minimize or avoid external heat sources (direct sunlight, heating pads, etc.), which can trigger the release and absorption of too much medication and cause potentially deadly complications.

Combat medicine

USAF Pararescue combat medics in Afghanistan used fentanyl lozenges in the form of lollipops on combat casualties from IED blasts and other trauma. The stick is taped to a finger and the lozenge put in the cheek of the person. When enough fentanyl has been absorbed, the (sedated) person generally lets the lollipop fall from the mouth, indicating sufficient analgesia and somewhat reducing the likelihood of overdose and associated risks.

Dyspnea

Fentanyl can also be used for patients in whom morphine is not tolerated, or whose breathlessness is refractory to morphine. Fentanyl is especially useful for concomitant treatment in palliative care settings where pain and shortness of breath are severe and need to be treated with high strength opioids.

Other

Some routes of administration such as nasal sprays and inhalers generally result in a faster onset of high blood levels, which can provide more immediate analgesia but also more severe side effects, especially in overdose. The much higher cost of some of these appliances may not be justified by marginal benefit compared with buccal or oral options. Intranasal fentanyl appears to be equally effective as IV morphine and superior to intramuscular morphine for the management of acute hospital pain.

A fentanyl patient-controlled transdermal system (PCTS) is under development, which aims to allow patients to control administration of fentanyl through the skin to treat postoperative pain. The technology consists of a "preprogrammed, self-contained drug-delivery system" that uses electrotransport technology to administer on-demand does of 40 µg of fentanyl hydrochloride over ten minutes. In a 2004 experiment including 189 patients with moderate to severe postoperative pain up to 24 hours after major surgery, 25% of patients withdrew due to inadequate analgesia. However, the PCTS method proved superior to the placebo, showing lower mean VAS pain scores and having no significant respiratory depression effects.

Adverse effects

Fentanyl's most common side effects, which affect more than 10% of people, include nausea, vomiting, constipation, dry mouth, somnolence, confusion, and asthenia (weakness). Less frequently, in 3–10% of people, fentanyl can cause abdominal pain, headache, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss, dizziness, nervousness, anxiety, depression, flu-like symptoms, dyspepsia (indigestion), shortness of breath, hypoventilation, apnoea, and urinary retention. Fentanyl use has also been associated with aphasia. Despite being a more potent analgesic, fentanyl tends to induce less nausea, as well as less histamine-mediated itching, than morphine.

The duration of action of fentanyl has sometimes been underestimated, leading to harm in a medical context. In 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began investigating several respiratory deaths, but doctors in the United Kingdom were not warned of the risks with fentanyl until September 2008. The FDA reported in April 2012 that twelve young children had died and twelve more made seriously ill from separate accidental exposures to fentanyl skin patches.

Respiratory depression

The most dangerous adverse effect of fentanyl is respiratory depression, that is, decreased sensitivity to carbon dioxide leading to reduced rate of breathing, which can cause anoxic brain injury or death. This risk is decreased when the airway is secured with an endotracheal tube (as during anesthesia). This risk is higher in specific groups, like those with obstructive sleep apnea.

Other factors that increase the risk of respiratory depression are:

- High fentanyl doses

- Sleep

- Older age

- Simultaneous use of CNS depressants like benzodiazepines, barbiturates, alcohol, and inhaled anesthetics

- Hyperventilation

- Decreased CO2 levels in the serum

- Respiratory acidosis

- Decreased fentanyl clearance from the body

- Decreased blood flow to the liver

- Renal insufficiency

Sustained release fentanyl preparations, such as patches, may also produce unexpected delayed respiratory depression. The precise reason for sudden respiratory depression is unclear, but there are several hypotheses:

- Saturation of the body fat compartment in people with rapid and profound body fat loss (people with cancer, cardiac or infection-induced cachexia can lose 80% of their body fat).

- Early carbon dioxide retention causing cutaneous vasodilation (releasing more fentanyl), together with acidosis, which reduces protein binding of fentanyl, releasing yet more fentanyl.

- Reduced sedation, losing a useful early warning sign of opioid toxicity and resulting in levels closer to respiratory-depressant levels.

Another related complication of fentanyl overdoses includes the so-called wooden chest syndrome, which quickly induces complete respiratory failure by paralyzing the thoracic muscles, explained in more detail in the Muscle rigidity section below.

Heart and blood vessels

- Bradycardia: Fentanyl decreases the heart rate by increasing vagal nerve tone in the brainstem, which increases the parasympathetic drive.

- Vasodilation: It also vasodilates arterial and venous blood vessels through a central mechanism, by primarily slowing down vasomotor centers in the brainstem. To a lesser extent, it does this by directly affecting blood vessels. This is much more profound in patients who have an already increased sympathetic drive, like patients who have high blood pressure or congestive heart failure. It does not affect the contractility of the heart when regular doses are administered.

Muscle rigidity

If high boluses of fentanyl are administered quickly, muscle rigidity of the vocal cords can make bag-mask ventilation very difficult. The exact mechanism of this effect is unknown, but it can be prevented and treated using neuromuscular blockers.

Wooden chest syndrome

A prominent idiosyncratic adverse effect of fentanyl also includes a sudden onset of rigidity of the abdominal muscles and the diaphragm, which induces respiratory failure; this is seen with high doses and is known as wooden chest syndrome. The syndrome is believed to be the main cause of death as a result of fentanyl overdoses.

Wooden chest syndrome is reversed by naloxone and is believed to be caused by a release of noradrenaline, which activates α-adrenergic receptors and also possibly via an activation of cholinergic receptors.

Wooden chest syndrome is unique to the most powerful opioids—which today comprise fentanyl and its analogs—while other less-powerful opioids like heroin produce mild rigidity of the respiratory muscles to a much lesser degree.

Overdose

Fentanyl poses an exceptionally high overdose risk in humans. This is because the amount required to cause toxicity is unpredictable. In its pharmaceutical form most overdose deaths attributed solely to fentanyl occurring at serum concentrations at a mean of 0.025 µg/mL, with a range 0.005–0.027 µg/mL. In contexts of poly-substance use, blood fentanyl concentrations of approximately 7 ng/ml or greater have been associated with fatalities. Over 85% of overdoses involved at least one other drug, and there was no clear correlation showing at which level the mixtures were fatal. The dosages of fatal mixtures varied by over three magnitudes in some cases. This extremely unpredictable volatility with other drugs makes it especially difficult to avoid fatalities.

Naloxone (sold under the brand name Narcan) can completely or partially reverse an opioid overdose. In July 2014, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) of the UK issued a warning about the potential for life-threatening harm from accidental exposure to transdermal fentanyl patches, particularly in children, and advised that they should be folded, with the adhesive side in, before being discarded. The patches should be kept away from children, who are most at risk from fentanyl overdose. In the US, fentanyl and fentanyl analogs caused over 29,000 deaths in 2017, a large increase over the previous four years.

Some increases in fentanyl deaths do not involve prescription fentanyl but are related to illicitly made fentanyl that is being mixed with or sold as heroin. Death from fentanyl overdose continues to be a public health issue of national concern in Canada since September 2015. In 2016, deaths from fentanyl overdoses in the province of British Columbia averaged two persons per day. In 2017 the death rate rose over 100% with 368 overdose-related deaths in British Columbia between January and April 2017.

Fentanyl has started to make its way into heroin as well as illicitly manufactured opioids and benzodiazepines. Fentanyl contamination in cocaine, methamphetamine, ketamine, MDMA, and other drugs is common. A kilogram of heroin laced with fentanyl may sell for more than US$100,000, but the fentanyl itself may be produced far more cheaply, for about US$6,000 per kilogram. While Mexico and China are the primary source countries for fentanyl and fentanyl-related substances trafficked directly into the United States, India is emerging as a source for finished fentanyl powder and fentanyl precursor chemicals.. The United Kingdom illicit drug market is no longer reliant on China, as domestic fentanyl production is replacing imports.

The intravenous dose causing 50% of opioid-naive experimental subjects to die (LD50) is "3 mg/kg in rats, 1 mg/kg in cats, 14 mg/kg in dogs, and 0.03 mg/kg in monkeys." The LD50 in mice has been given as 6.9 mg/kg by intravenous administration, 17.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally, 27.8 mg/kg by oral administration. The LD50 in humans is unknown, but it is estimated that the lethal dose may be as low as 2 mg in some people depending on body size, tolerance, and past usage.

False reports by police of poisonings through secondary exposure

In the late 2010s, some media outlets began to report stories of police officers being hospitalised after touching powdered fentanyl, or after brushing it from their clothing.Topical (or transdermal; via the skin) and inhalative exposure to fentanyl is extremely unlikely to cause intoxication or overdose (except in cases of prolonged exposure with very large quantities of fentanyl), and first responders such as paramedics and police officers are at minimal risk of fentanyl poisoning through accidental contact with intact skin. A 2020 article from the Journal of Medical Toxicology stated that "the consensus of the scientific community remains that illness from unintentional exposures is extremely unlikely, because opioids are not efficiently absorbed through the skin and are unlikely to be carried in the air." The effects being reported in these cases, including rapid heartbeat, hyperventilation and chills, were not symptoms of a fentanyl overdose, and were more commonly associated with a panic attack.

A 2021 paper expressed concern that these physical fears over fentanyl may inhibit effective emergency response to overdoses by causing responding officers to spend additional time on unnecessary precautions, and that the media coverage could also perpetuate a wider social stigma that people who use drugs are dangerous to be around.

Prevention

Public health advisories to prevent fentanyl misuse and fatal overdose have been issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). An initial HAN Advisory, also known as a Health Alert Network Advisory ("provides vital, time-sensitive information for a specific incident or situation; warrants immediate action or attention by health officials, laboratorians, clinicians, and members of the public; and conveys the highest level of importance") was issued during October 2015. A subsequent HAN Alert was issued in July 2018, warning of rising numbers of deaths due to fentanyl abuse and mixing with non-opioids. A December 2020 HAN Advisory warned of:

substantial increases in drug overdose deaths across the United States, primarily driven by rapid increases in overdose deaths involving... illicitly manufactured fentanyl; a concerning acceleration of the increase in drug overdose deaths, with the largest increase recorded from March 2020 to May 2020, coinciding with the implementation of widespread mitigation measures for the COVID-19 pandemic; significant increases in overdose deaths involving methamphetamine.

81,230 drug overdose deaths occurred during the 12 months from May 2019 to May 2020, the largest number of drug overdoses for a 12-month interval ever recorded for the U.S. The CDC recommended the following four actions to counter this rise:

- local need to expand the distribution and use of naloxone and overdose prevention education,

- expand awareness, access, and availability of treatment for substance use disorders,

- intervene early with individuals at highest risk for overdose, and

- improve detection of overdose outbreaks to facilitate more effective response.

Another initiative is a social media campaign from the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) called "One Pill Can Kill". This social media campaign's goal is to spread awareness of the prevalence of counterfeit pills that are being sold in America that are leading to the large overdose epidemic in America. This campaign also shows the difference between counterfeit pills and real pills. It also offers resources for help with drug addiction and rehabilitation.

Pharmacology

Classification

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid in the phenylpiperidine family, which includes sufentanil, alfentanil, remifentanil, and carfentanil. Some fentanyl analogues, such as carfentanil, are up to 10,000 times stronger than morphine.

Structure-activity

The structures of opioids share many similarities. Whereas opioids like codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and hydromorphone are synthesized by simple modifications of morphine, fentanyl and its relatives are synthesized by modifications of meperidine. Meperidine is a fully synthetic opioid, and other members of the phenylpiperidine family like alfentanil and sufentanil are complex versions of this structure.

Like other opioids, fentanyl is a weak base that is highly lipid-soluble, protein-bound, and protonated at physiological pH. All of these factors allow it to rapidly cross cellular membranes, contributing to its quick effect in the body and the central nervous system.

Mechanism of action

| Affinities, Ki | Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR:DOR:KOR |

| 0.39 nM | >1,000 nM | 255 nM | 1:>2564:654 |

Fentanyl, like other opioids, acts on opioid receptors. These receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors, which contain seven transmembrane portions, intracellular loops, extracellular loops, intracellular C-terminus, and extracellular N-terminus. The extracellular N-terminus is important in differentiating different types of binding substrates. When fentanyl binds, downstream signaling leads to the inhibitory effects, such as decreased cAMP production, decreased calcium ion influx, and increased potassium efflux. This inhibits the ascending pathways in the central nervous system to increase pain threshold by changing the perception of pain; this is mediated by decreasing propagation of nociceptive signals, resulting in analgesic effects.

As a μ-receptor agonist, fentanyl binds 50 to 100 times more potently than morphine. It can also bind to the delta and kappa opioid receptors but with a lower affinity. It has high lipid solubility, allowing it to more easily penetrate the central nervous system. It attenuates "second pain" with primary effects on slow-conducting, unmyelintated C-fibers and is less effective on neuropathic pain and "first pain" signals through small, myelinated A-fibers.

Fentanyl can produce the following clinical effects strongly, through μ-receptor agonism:

- Supraspinal analgesia (μ1)

- Respiratory depression (μ2)

- Physical dependence

- Muscle rigidity

It also produces sedation and spinal analgesia through Κ-receptor agonism.

Therapeutic effects

- Pain relief: Primarily, fentanyl provides the relief of pain by acting on the brain and spinal μ-receptors.

- Sedation: Fentanyl produces sleep and drowsiness, as the dosage is increased, and can produce the δ-waves often seen in natural sleep on electroencephalogram.

- Suppression of the cough reflex: Fentanyl can decrease the struggle against an endotracheal tube and excessive coughing by decreasing the cough reflex, becoming useful when intubating people who are awake and have compromised airways. After receiving a bolus dose of fentanyl, people can also experience paradoxical coughing, which is a phenomenon that is not well understood.

Detection in biological fluids

Fentanyl may be measured in blood or urine to monitor for abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Commercially available immunoassays are often used as initial screening tests, but chromatographic techniques are generally used for confirmation and quantitation. The Marquis Color test may also be used to detect the presence of fentanyl. Using formaldehyde and sulfuric acid, the solution will turn purple when introduced to opium drugs. Blood or plasma fentanyl concentrations are expected to be in a range of 0.3–3.0 μg/L in persons using the medication therapeutically, 1–10 μg/L in intoxicated people, and 3–300 μg/L in victims of acute overdosage.Paper spray-mass spectrometry (PS-MS) may be useful for initial testing of samples.

Synthesis

Fentanyl is a 4-anilopiperidine class synthetic opioid. The synthesis of Fentanyl is accomplished by one of four main methods as reported in scientific literature: the Janssen, Seigfried, Gupta, or Suh method.

Janssen Method

The original synthesis as patented in 1964 by Dr. Paul Janssen involves synthesis of benzylfentanyl from N-Benzyl-4-Piperidone. The resulting benzylfentanyl is used as feedstock to norfentanyl. It is norfentanyl that forms fentanyl upon reaction with phenethyl chloride. A portion of the Janssen Method is shown below, in this instance, to synthesize a related opioid.

Seigfried Method

The Seigfried method involves the initial synthesis of N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (NPP). This NPP byproduct is reductively aminated to 4-anilino-N-phenethylpiperidine (4-ANPP). Fentanyl is produced following the reaction of 4-ANPP with an acyl chloride. The Seigfried method has been used in the early 2000s to manufacture fentanyl in both domestic and foreign clandestine laboratories.

Gupta Method

The Gupta (or 'one-pot') method starts from 4-Piperidone and skips the direct use of 4-ANPP/NPP; rather the compounds are formed only as impurities or temporary intermediates. In a 2021 study of 318 seized samples, the Gupta method was the predominant synthesis route in samples analyzed by the Fentanyl Profiling Program (FPP). The average purity of these Gupta-synthesized samples was 13.6%, with an overall range of 0.2% to 36.4%.

Suh Method

The Suh (or 'total synthesis') method skips the direct use of piperidine precursors in favor of creating the ring system in-situ. The portion of this synthesis leading to the in-situ formation of NPP is what is shown to the right.

History

Fentanyl was first synthesized in Belgium by Paul Janssen under the label of his relatively newly formed Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1959. It was developed by screening chemicals similar to pethidine (meperidine) for opioid activity. The widespread use of fentanyl triggered the production of fentanyl citrate (the salt formed by combining fentanyl and citric acid in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio). Fentanyl citrate entered medical use as a general anaesthetic in 1968, manufactured by McNeil Laboratories under the trade name Sublimaze.

In the mid-1990s, Janssen Pharmaceutica developed and introduced into clinical trials the Duragesic patch, which is a formulation of an inert alcohol gel infused with select fentanyl doses, which are worn to provide constant administration of the opioid over a period of 48 to 72 hours. After a set of successful clinical trials, Duragesic fentanyl patches were introduced into medical practice.

Following the patch, a flavored lollipop of fentanyl citrate mixed with inert fillers was introduced in 1998 under the brand name of Actiq, becoming the first quick-acting formation of fentanyl for use with chronic breakthrough pain.

In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Onsolis (fentanyl buccal soluble film), a fentanyl drug in a new dosage form for cancer pain management in opioid-tolerant subjects. It uses a medication delivery technology called BEMA (BioErodible MucoAdhesive), a small dissolvable polymer film containing various fentanyl doses applied to the inner lining of the cheek.

Fentanyl has a US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Administrative Controlled Substances Code Number (ACSCN) of 9801. Its annual aggregate manufacturing quota has significantly reduced in recent years from 2,300 kg in 2015 and 2016 to only 731.452 kg in 2021, a nearly 68.2% decrease.

Society and culture

Legal status

In the UK, fentanyl is classified as a controlled Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

In the Netherlands, fentanyl is a List I substance of the Opium Law.

In the U.S., fentanyl is a Schedule II controlled substance per the Controlled Substance Act. Distributors of Abstral are required to implement an FDA-approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program. In order to curb misuse, many health insurers have begun to require precertification and/or quantity limits for Actiq prescriptions.

In Canada, fentanyl is considered a schedule I drug as listed in Canada's Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

Estonia is known to have been home to the world's longest documented fentanyl epidemic, especially following the Taliban ban on opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan.

A 2018 report by The Guardian indicated that many major drug suppliers on the dark web have voluntarily banned the trafficking of fentanyl.

The fentanyl epidemic has erupted in a highly acrimonious dispute between the U.S. and Mexican governments. While U.S. officials blame the flood of fentanyl crossing the border primarily on Mexican crime groups, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, insists that the main source of this synthetic drug is Asia. He believes that the crisis of a lack of family values in the United States that drives people to use the drug.

Recreational use

Illicit use of pharmaceutical fentanyl and its analogues first appeared in the mid-1970s in the medical community and continues in the present. More than 12 different analogues of fentanyl, all unapproved and clandestinely produced, have been identified in the U.S. drug traffic. In February 2018, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration indicated that illicit fentanyl analogs have no medically valid use, and thus applied a "Schedule I" classification to them.

Fentanyl analogues may be hundreds of times more potent than heroin. Fentanyl is used orally, smoked, snorted, or injected. Fentanyl is sometimes sold as heroin or oxycodone, which can lead to overdose. Many fentanyl overdoses are initially classified as heroin overdoses. Recreational use is not particularly widespread in the EU except for Tallinn, Estonia, where it has largely replaced heroin. Estonia has the highest rate of 3-methylfentanyl overdose deaths in the EU, due to its high rate of recreational use.

Fentanyl is sometimes sold on the black market in the form of transdermal fentanyl patches such as Duragesic, diverted from legitimate medical supplies. The gel from inside the patches is sometimes ingested or injected.

Another form of fentanyl that has appeared on the streets is the Actiq lollipop formulation. The pharmacy retail price ranges from US$15 to US$50 per unit based on the strength of the lozenge, with the black market cost ranging from US$5 to US$25, depending on the dose. The attorneys general of Connecticut and Pennsylvania have launched investigations into its diversion from the legitimate pharmaceutical market, including Cephalon's "sales and promotional practices for Provigil, Actiq and Gabitril."

Non-medical use of fentanyl by individuals without opioid tolerance can be very dangerous and has resulted in numerous deaths. Even those with opiate tolerances are at high risk for overdoses. Like all opioids, the effects of fentanyl can be reversed with naloxone, or other opiate antagonists. Naloxone is increasingly available to the public. Long acting or sustained release opioids may require repeat dosage. Illicitly synthesized fentanyl powder has also appeared on the United States market. Because of the extremely high strength of pure fentanyl powder, it is very difficult to dilute appropriately, and often the resulting mixture may be far too strong and, therefore, very dangerous.

Some heroin dealers mix fentanyl powder with heroin to increase potency or compensate for low-quality heroin. In 2006, illegally manufactured, non-pharmaceutical fentanyl often mixed with cocaine or heroin caused an outbreak of overdose deaths in the United States and Canada, heavily concentrated in the cities of Dayton, Ohio; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Enforcement

Several large quantities of illicitly produced fentanyl have been seized by U.S. law enforcement agencies. In November 2016, the DEA uncovered an operation making counterfeit oxycodone and Xanax from a home in Cottonwood Heights, Utah. They found about 70,000 pills in the appearance of oxycodone and more than 25,000 in the appearance of Xanax. The DEA reported that millions of pills could have been distributed from this location over the course of time. The accused owned a tablet press and ordered fentanyl in powder form from China. A seizure of a record amount of fentanyl occurred on 2 February 2019, by U.S. Customs and Border Protection in Nogales, Arizona. The 254 pounds (115 kg) of fentanyl, which was estimated to be worth US$3.5M, was concealed in a compartment under a false floor of a truck transporting cucumbers. The "China White" form of fentanyl refers to any of a number of clandestinely produced analogues, especially α-methylfentanyl (AMF). One US Department of Justice publication lists "China White" as a synonym for a number of fentanyl analogues, including 3-methylfentanyl and α-methylfentanyl, which today are classified as Schedule I drugs in the United States. Part of the motivation for AMF is that, despite the extra difficulty from a synthetic standpoint, the resultant drug is more resistant to metabolic degradation. This results in a drug with an increased duration.

In June 2013, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory to emergency departments alerting to 14 overdose deaths among intravenous drug users in Rhode Island associated with acetylfentanyl, a synthetic opioid analog of fentanyl that has never been licensed for medical use. In a separate study conducted by the CDC, 82% of fentanyl overdose deaths involved illegally manufactured fentanyl, while only 4% were suspected to originate from a prescription.

Beginning in 2015, Canada has seen a number of fentanyl overdoses. Authorities suspected that the drug was being imported from Asia to the western coast by organized crime groups in powder form and being pressed into pseudo-OxyContin tablets. Traces of the drug have also been found in other recreational drugs, including cocaine, MDMA, and heroin. The drug has been implicated in deaths of people from all walks of life—from homeless individuals to professionals—including teens and young parents. Because of the rising deaths across the country, especially in British Columbia where 1,716 deaths were reported in 2020 and 1,782 from January to October 2021,Health Canada is putting a rush on a review of the prescription-only status of naloxone in an effort to combat overdoses of the drug. In 2018, Global News reported allegations that diplomatic tensions between Canada and China hindered cooperation to seize imports, with Beijing being accused of inaction.

Fentanyl has been discovered for sale in illicit markets in Australia in 2017 and in New Zealand in 2018. In response, New Zealand experts called for wider availability of naloxone.

In May 2019, China regulated the entire class of fentanyl-type drugs and two fentanyl precursors. Nevertheless, it remains the principal origin of fentanyl in the United States: Mexican cartels source fentanyl precursors from Chinese suppliers such as Yuancheng Group, which are finished in Mexico and smuggled to the United States. Following the 2022 visit by Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, China halted cooperation with the United States on combatting drug trafficking.

India has also emerged as a source of fentanyl and fentanyl precursors, where Mexican cartels have already developed networks for the import of synthetic drugs. It is possible that fentanyl and precursor production may disperse to other countries, such as Nigeria, South Africa, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Netherlands.

In 2020, the Myanmar military and police confiscated 990 gallons of methyl fentanyl, as well as precursors for the illicit synthesis of the drug. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the Shan State of Myanmar has been identified as a major source for fentanyl derivatives. In 2021, the agency reported a further drop in opium poppy cultivation in Burma, as the region's synthetic drug market continues to expand and diversify.

In 2023, a California police union director was charged with importing synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and tapentadol disguised as chocolate. U.S. law enforcement had been slow in their response to the fentanyl crisis, according to the Washington Post. The response by the federal government to the fentanyl crisis had also faltered, according to the press release. Overdose deaths by fentanyl and other illegally imported opioids were surging since 2019 and are presently a major cause of death in all U.S. states.

According to the national archives and the DEA, direct fentanyl shipments from China have stopped since 2022. The majority of illicit fentanyl and analogues now entering the U.S. from Mexico are final products in form of "tablets" and adulterated heroin from previously synthesized fentanyl. From the sophistication of full fentanyl synthesis and acute toxicity in laboratory environments, 'clandestine' labs in Mexico relate to making an illicit dosage form from available fentanyl rather than the synthesis itself. Based on further research by investigators, fentanyl and analogues are likely synthesized in labs that have the appearance of a legal entity, or are diverted from pharmaceutical laboratories.

Recalls

In February 2004, a leading fentanyl supplier, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products recalled one lot, and later, additional lots of fentanyl (brand name: Duragesic) patches because of seal breaches that might have allowed the medication to leak from the patch. A series of class II recalls was initiated in March 2004, and in February 2008, the ALZA Corporation recalled their 25 µg/h Duragesic patches due to a concern that small cuts in the gel reservoir could result in accidental exposure of patients or health care providers to the fentanyl gel.

Brand names

Brand names include Sublimaze, Actiq, Durogesic, Duragesic, Fentora, Matrifen, Haldid, Onsolis, Instanyl, Abstral, Lazanda and others.

Cost

In the United States, the 800 mcg tablet was 6.75 times more expensive as of 2020 than the lozenge. As of 2023, the average cost for an injectable fentanyl solution (50 mcg/mL) is around US$17 for a supply of 20 milliliters, depending on the pharmacy. In a 2020 report by the Australian Institute of Criminology, a 100-microgram transdermal patch was valued from between AU$75 and AU$450 on illicit markets. Furthermore, in another 2020 study, the average price per gram of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl on various cryptomarkets was US$1,470.40 for offerings of less than five grams; the average for offers over five grams was US$139.50. In addition, on DreamMarket furanfentanyl (Fu-F), the most common analog on said market, the average price per gram was US$243.10 for retail listings and US$26.50 per gram for wholesale listings.

Storage and disposal

The fentanyl patch is one of a few medications that may be especially harmful, and in some cases fatal, with just one dose, if misused by a child. Experts have advised that any unused fentanyl patches be kept in a secure location out of children's sight and reach, such as a locked cabinet.

In British Columbia, Canada, where there are environmental concerns about toilet flushing or garbage disposal, pharmacists recommend that unused patches be sealed in a child-proof container that is then returned to a pharmacy. In the United States where patches cannot always be returned through a medication take-back program, flushing is recommended for fentanyl patches, because it is the fastest and surest way to remove them from the home to prevent ingestion by children, pets or others not intended to use them.

Notable deaths

- American professional wrestler Anthony Durante, also known as "Pitbull #2", died on 25 September 2003 from a fentanyl-induced overdose.

- Wilco guitarist Jay Bennett died on 24 May 2009 from an accidental overdose of fentanyl, shortly after he publicly revealed that he needed hip replacement surgery which he could not afford due to his health insurance considering the situation a "pre-existing condition."

- Slipknot bassist Paul Gray died on 24 May 2010 from an overdose of morphine and fentanyl.

- Medical examiners concluded that musician Prince died on 21 April 2016 from an accidental fentanyl overdose. Fentanyl was among many substances identified in counterfeit pills recovered from his home, especially some that were mislabeled as Watson 385, a combination of hydrocodone and paracetamol.

- Author & journalist Michelle McNamara died on 21 April 2016 from an accidental overdose; medical examiners determined fentanyl was a contributing factor.

- Canadian video game composer Saki Kaskas died of a fentanyl overdose on 11 November 2016; he had been battling heroin addiction for over a decade.

- American rapper Lil Peep died of an accidental fentanyl overdose on 15 November 2017.

- On 19 January 2018, the medical examiner-coroner for the county of Los Angeles said musician Tom Petty died from an accidental drug overdose as a result of mixing medications that included fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl, and despropionyl fentanyl (among others). He was reportedly treating "many serious ailments" that included a broken hip.

- In 2018, American rapper Mac Miller died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl, cocaine and alcohol.

- On 16 December 2018, American tech entrepreneur Colin Kroll, founder of social media video-sharing app Vine and quiz app HQ Trivia, died from an overdose of fentanyl, heroin, and cocaine.

- On 1 July 2019, American baseball player Tyler Skaggs died from pulmonary aspiration while under the influence of fentanyl, oxycodone, and alcohol.

- On 1 January 2020, American rapper, singer, and songwriter Lexii Alijai died from accidental toxicity resulting from the combination of alcohol and fentanyl.

- On 20 August 2020, American singer, songwriter and musician Justin Townes Earle died from an accidental overdose caused by cocaine laced with fentanyl.

- On 24 August 2020, Riley Gale, frontman for the Texas metal band Power Trip, died as a result of the toxic effects of fentanyl in a manner that was ruled accidental.

- On 22 April 2021, Digital Underground frontman, rapper, and musician Shock G died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl, meth, and alcohol.

- On 6 September 2021, actor Michael K. Williams, who rose to fame through his critically acclaimed role as Omar Little on the HBO drama series The Wire, died from an overdose of fentanyl, parafluorofentanyl, heroin, and cocaine.

- 6 April 2023: Jarez Posey, the manager of US rapper Coolio (Artis Leon Ivey, Jr) attributes his death to fentanyl, according to press reports.

Domestic use

In August 2018, Nebraska became the first American state to use fentanyl to execute a prisoner.Carey Dean Moore, at the time one of the longest-serving death row inmates in the United States, was executed at the Nebraska State Penitentiary. Moore received a lethal injection, administered as an intravenous series of four drugs that included fentanyl citrate, to inhibit breathing and render the subject unconscious. The other drugs included diazepam as a tranquilizer, cisatracurium besylate as a muscle relaxant, and potassium chloride to stop the heart. The use of fentanyl in execution caused concern among death penalty experts because it was part of a previously untested drug cocktail. The execution was also protested by anti-death penalty advocates at the prison during the execution and later at the Nebraska capitol building.

Russian Spetsnaz security forces are suspected to have used a fentanyl analogue, or derivative (suspected to be carfentanil and remifentanil), to incapacitate people rapidly in the Moscow theater hostage crisis in 2002. The siege was ended, but several hostages died from the gas after their health was severely taxed during the days long siege. The Russian Health Minister later stated that the gas was based on fentanyl, but the exact chemical agent has not been clearly identified.

Veterinary use

Fentanyl is commonly used for analgesia and as a component of balanced sedation and general anesthesia in small animal patients. In addition, its efficacy is higher than many other pure-opiate and synthetic pure-opioid agonists regarding vomiting, depth of sedation, and cardiovascular effects when given as a continuous infusion as well as a transdermal patch. As with other pure-opioid agonists, fentanyl has been associated with dysphoria in dogs.

Furthermore, transdermal fentanyl's potency and short duration of action make it popular as an intra-operative and post-operative analgesic in cats and dogs. This is usually done with off-label fentanyl patches manufactured for humans with chronic pain. In 2012, a highly concentrated (50 mg/mL) transdermal solution, trade name Recuvyra, has become commercially available for dogs only. It is FDA approved to provide four days of analgesia after a single application before surgery. It is not approved for multiple doses or other species. The drug is also approved in Europe.

Further reading

- Tschirhart JN, Zhang S (October 2020). "Fentanyl-Induced Block of hERG Channels Is Exacerbated by Hypoxia, Hypokalemia, Alkalosis, and the Presence of hERG1b". Molecular Pharmacology. 98 (4): 508–517. doi:10.1124/mol.119.119271. PMID 32321735. S2CID 216084895.

External links

- Fentanyl (Report). Emergency Response Database. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 8 July 2021.

| Inhalational | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injection |

|

||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| MOR |

|

|---|---|

| DOR |

|

| KOR |

|

| NOP |

|

| Unsorted | |

| Others |

|

| CAR |

|

|---|---|

| PXR |

|

| |